So what better alternative is there than an agreement between citizens themselves reached under conditions that are fair for all?

John Rawls, Justice as Fairness, para. 6.1

1

The quote above is based on Rawls’s theory of justice, where the concept of justice is one based on fairness. [1] To achieve fair terms of cooperation between citizens regarded as free and equal, Rawls proposes a hypothetical scenario—the ‘original position’ thought experiment—in which a group of people is set the task of reaching an agreement regarding the political and economic structure in which they are prepared to live. [2] Each individual, however, has to act behind a ‘veil of ignorance’, that is, not knowing the physical or material attributes that characterises them. [3] They lack knowledge, for example, of their gender, race, age, intelligence, skills, wealth, education, and religion. The idea is that people are unlikely to propose structures that are fundamentally unjust on the basis of any of these attributes. [4] Rawls’s theory is founded on a hypothetical scenario, an ideal to which we all ought to aspire. [5] But what would a real-life scenario look like, one that is historically contingent and in which the conditions for a fair agreement are mired in factual constraints, including not simply relative bargaining power, but also the influence of ideology?

2

In this article, I put one such scenario under detailed examination: the latest, ongoing, EU copyright reform. Taking the Fair Internet for Performers Campaign as a case study, I focus on the way in which EU stakeholders in the copyright debate conceive of fairness. I pay particular attention to the political process leading to copyright reform and less so to the normative considerations of the rights being campaigned for or indeed of the concept of fairness itself. Instead, I consider how discourse about fairness is employed and ideologically framed in relation to this particular performers’ rights campaign, including discourse as found in the media, reform documents, and in stakeholder interactions. As part of a larger project on performers’ rights in the UK music industries, my perspective of the lobbying process reflects a UK position in its approach to the EU. Differences in music copyright are significant across jurisdictions, but it is important to recognise that debates around music copyright reproduce the international status of campaigning stars and multi-national corporations.

3

Serious discussion about a new copyright reform at the European level since the last major overhaul in 2001 through the InfoSoc Directive, began in the context of the 2014-2019 European Commission presidency of Jean-Claude Juncker. His political guidelines set out 10 priorities of which ‘A connected digital single market’ provided the context to ‘modernis[e] copyright rules in the light of the digital revolution and consumer behaviour’. [6] With the dramatic technological changes of the last 15 years, including the rise of Spotify, YouTube and Netflix, the time was ripe for such reform.

4

Since at least 2013, when Thom Yorke complained about the exploitative strategies of the record industry by describing Spotify as the ‘last fart of a dying corpse’, many more artists had expressed their dissatisfaction with the direction that the record industry was taking with streaming services. [7] Taylor Swift has been perhaps the most outspoken about the small fees offered by music streaming sites. In November 2014, Swift removed most of her catalogue from Spotify, explaining her decision on a Yahoo! interview: ‘I'm not willing to contribute my life's work to an experiment that I do not feel fairly compensates the writers, producers, artists and creators of this music’, she said referring to Spotify’s free tier. [8] Half a year later, on the day of the launch of Apple’s streaming site, Swift wrote an open letter published on her Tumblr account expressing her outrage at Apple’s free three-month trial, during which musicians would not be compensated: ‘Three months is a long time to go unpaid, and it is unfair to ask anyone to work for nothing’. [9] Her appeal was effective: Apple immediately backtracked that proposal.

5

Nonetheless, Swift has not been the only one protesting against the streaming sites’ poor pay. Other artists have taken a stance on streaming: Beyoncé and Kanye West have offered exclusives with high mark-ups on Tidal, while Adele has refused to launch new music on streaming. Although not alone in her campaign for better pay from streaming companies, Swift was one of the most visible contenders to introduce the concept of fairness into these public debates. Acknowledging that these artists operate in different jurisdictions and have a variety of different claims to copyright, it is this fraught relationship with streaming services that launched the concept of fairness into the mainstream and formed the backdrop of campaigns such as the Fair Internet for Performers Campaign (henceforth the FIPC). [10]

6

The FIPC was launched in May 2015 in the context of the European process of copyright reform. It seeks to secure royalty payments for performers when their recorded performance is played on streaming and other on-demand services offered by digital service providers (DSPs), such as Spotify and Netflix. Currently, record labels (and some label services) only negotiate royalty payments in relation to use on DSPs with featured artists. In contrast, the majority of performers do not have the bargaining power to negotiate standard contracts: record companies offer performers a one-off fee in return for assigning them the performers’ exclusive right of making available to the public. [11]

7

The legal instrument proposed by the campaign to address this problem is the addition of an unwaivable equitable remuneration right to the existing exclusive making-available right. This would secure collective remuneration whilst leaving the possibility of negotiating the exclusive right untouched. [12] The campaign is targeted at the European Union, with the aim of arriving at a legal solution within the current copyright reform. When the campaign entered the reform process, discussion about ‘fair remuneration’ for authors and performers was slowly gaining traction. However, the tool chosen by the European Commission in its 2016 proposal to address the low bargaining power of the majority of creators was different to that of the FIPC: the EC proposed to regulate transparency and combine it with contractual mechanisms to give authors and performers greater contractual bargaining power. [13]

8

In this article I trace the concept of ‘fairness’ throughout the European process of copyright reform. I draw on two main sets of data: on the one hand, I examine primary literature from the European Commission (EC) and Parliament, including the EC political guidelines, the EC Proposal for Copyright in the Digital Single Market, and key documents created by the Parliament in response to the proposal. On the other, I interrogate the accounts of stakeholders involved in the reform process as related in personal interviews. I build on current research that investigates the processes by which copyright law is reformed [14] and that considers how rights holders employ discourse strategically in order to advance and legitimate their claims within the current copyright regime. [15] As Street, Laing and Schroff argue, it is only by focusing on otherwise loosely employed terminology that the impact of legal and political reform can be assessed. [16] Edwards et al. in particular, attend to the fact that, in justifying their positions, stakeholders often appeal to principles of general interest that already enjoy some degree of legitimacy. [17] For example, ‘arguments that associate legal consumption with moral integrity are countered by discourses that reveal the inequitable nature of industry structures’. [18] The concept of ‘fairness’ has particular resonance in this context, where every stakeholder claims that this term is associated with equality, justice and legitimacy for him or herself.

9

By analysing the EC presidential guidelines, I present the setting within which the concept of fairness begins to be used within this presidential cycle. Drawing on Foucault’s idea of the net-like circulation of power, I describe the increase in currency of the word fairness throughout the reform process as generated by a ‘feedback loop’. [19] From its first use by Juncker to the EC Proposal and surrounding discourse (presented here in chronological order) this feedback loop develops its own self-reinforcing cycles of signification. Here the appropriation and re-appropriation of the word ‘fairness’ by members of the same conversation transform it into a buzz phrase for ‘a more balanced playing field in contractual relations between authors and performers and their contractual counterparts’. This feedback loop is not a random process: commissioners, politicians and campaigners deliberately echo Juncker’s choice of keywords and imbue them with their own meaning hoping to gain traction in the debate. Those who are successful in pushing their agendas will have their meaning adopted by the reform documents.

10

Yet this feedback loop does not occur in a vacuum. As I demonstrate, fairness is understood by the majority of stakeholders within a wider discourse dominated by neoliberal thought. Here, in stark contrast to Rawls’s ideal theory, fairness is one that allows market forces to act freely with minimum regulation. When regulation is introduced, this is done to address perceived market failures that affect individual entrepreneurialism, not collective labour. The language used especially by the Commission, but also by the Parliament, is one that refers to citizens in a distant, non-committal, manner. The only citizens worth mentioning in any detail are entrepreneurs, who are juxtaposed with corporations. The FIPC, which conceives of its population as the creative industries’ labour force, is thus confronted with a steep climb - that of challenging current dominant thought.

11

The Fair Internet for Performers Campaign was launched by four international organisations representing 500,000 musicians, actors and dancers: the Association of European Performers’ Organisations (AEPO-Artis), which is the European association of performers’ collective management organisations; the European branch of the International Federation of Actors (EuroFIA); the International Federation of Musicians (FIM), and the International Artist Organisation of Music (IAO), which represents featured artists. As I will explain in more detail below, although these groups converge in the campaign, they represent slightly different interests and have different agendas for supporting the campaign.

12

As outlined above, the campaign seeks the addition of a collective remuneration right for the exclusive right of making available, which is already in existence across EU member states. [20] This addition of an equitable remuneration right would be unwaivable: performers would not be able to license or assign it through contract, except to a collective management organisation managing these rights on their behalf. Thus, every performer whose recorded performance was made available on on-demand services would need to be paid royalties regardless of contractual agreements. In defence of powerful record companies that offer contracts in which performers are asked to assign all of their exclusive rights for a one-off fee, it could be claimed that performers are not forced to accept these terms. However, in the music industries, where the labour market is characterised by oversupply, performers with low bargaining power do not feel that they have a choice. [21]

13

This type of right is not a new idea. The right represents the counterpart to the UK’s unwaivable equitable remuneration right for communication to the public, which entitles performers to royalty payments when their recorded performances are broadcast and played in public spaces such as public houses, clubs, bars, retail stores and other commercial and non-commercial establishments. [22] The license fees for these rights are collected by collective management organisations (CMOs) for record companies on behalf of their contracted performers. In the UK, record companies then split this income on a 50/50 basis with performers.

14

The implementation of the making available right varies between EU member states; however, where equitable remuneration rights were introduced (e.g. Spain), the principle established with the equitable remuneration right for communication to the public remains the same. In order to cover running costs, European CMOs retain a percentage of the collected license fees (often in the region of 15 to 20 per cent). In interviews, I heard both good and negative comments about the efficiency and effectiveness of CMOs, [23] but the campaigners seem to agree that their job is good enough to trust them with the management of the proposed right.

15

The campaign demands that the cost of this new right be borne by digital service providers. Considering that the income of DSPs is limited, all the other stakeholders in the business of DSPs are uneasy about this campaign, as they would have to accommodate a new payee. As I will examine in detail below, these include users, record labels, and the DSPs themselves. Featured artists and their managers are often in a position to negotiate favourable contracts, so they are not entirely sure of the benefit of a collectively managed right.

16

Do performers need another equitable remuneration right? It is not my objective to determine whether the FIPC is indeed fair in a normative sense, but I explain both fundamental positions briefly. It could be argued against the FIPC that collectively managed rights erode the bargaining potential of exclusive rights. This is because exclusive rights allow performers to trade each of their rights for the perceived value of their performance, which varies from performer to performer. In contrast, a collectively managed right is often negotiated by the CMOs in collaboration with the relevant trade union on behalf of all performers, which results in a (low) set fee with management costs (at about 15 per cent for Phonographic Performance Limited [PPL]). Alternatively, if this right is added to an exclusive right, powerful record companies could claim that the license fee for that particular right (in this case the making available right) has already been taken care of collectively. They then will pull back at attempts to negotiate an additional fee. Supporters of the campaign argue that the argument for exclusive rights works best in a perfect free market, where all the parties have equal bargaining power. [24] But this is a winner-take-all market, where only a small minority has any bargaining power, whilst the vast majority of performers are forced to accept the terms offered by powerful contractors in order to make a living. [25]

17

The complex process through which law is made in the European Union is called the ‘ordinary legislative procedure’. [26] In its simplest description, the European Commission proposes legislation, which is amended by the European Parliament and passed on for approval by the Council of Ministers. In practice however, each of the bodies is involved in all stages; so for instance, while the EC gauges the need for reform, by opening consultations and commissioning reports, it also receives recommendations from the Parliament and Member States. At the later stage, the approval by the Council of Ministers is really a drawn-out negotiation between the Council and the Parliament, both of whom submit proposals to each other. Meanwhile, the Commission can change its proposal at any time. As Kretschmer has put it, ‘proposed legislation is a constantly moving target’. [27] This flexibility is especially relevant for the different stakeholders affected by a particular piece of legislation and whose work is to influence the process to their advantage.

18

In this section I analyse policy statements by looking out for the use of the word ‘fairness’. I begin with the presidential guidelines for the European Commission cycle 2014-2019 entitled ‘A New Start for Europe: My Agenda for Jobs, Growth, Fairness and Democratic Change. Political Guidelines for the next European Commission.’ Considering the use of ‘fairness’ in its title, I do not wish to promote a top-down approach to the use of the word, but rather to use these guidelines as a contextual starting point. I take the view that ‘fairness’ is continuously produced and reproduced by all of the actors involved in this chain of action that forms the copyright reform process. To quote Foucault on the circulation of power:

power is not to be taken to be a phenomenon of one individual’s power over others, [but] must be analysed as something which circulates […]. Power is employed and exercised through a net-like organisation. And not only do individuals circulate its thread; they are always in the position of simultaneously undergoing and exercising this power. [28]

19

As the concept of fairness progresses through the Vice-Presidency and Directorate General to the Commission and Parliament and is meanwhile adopted by copyright stakeholders, the concept gains a life of its own. As I will demonstrate, however, this process is not a random one, but one neatly framed by ideology.

20

In September 2014, following the launch of his presidency programme, Juncker consolidated the structure of the new European Commission designed to facilitate the implementation of the guidelines. [29] The structure consists of seven vice-presidents in addition to the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Policy & Security Policy, each leading one project. Former Estonian Prime Minister Andrus Ansip was given the task of leading the project team ‘A Digital Single Market’, overseeing the work of twelve Commissioners and their Directorate Generals (DGs). Within this project, Günther Oettinger, the Commissioner for DG Digital Economy and Society, was nominated to lead a copyright reform. On Oettinger’s promotion, this role was taken over temporarily by Andrus Ansip, [30] and finally by Mariya Gabriel in July 2017. [31]

21

In the political guidelines, the words ‘fair’ or ‘fairness’ appeared 13 times, six times when referring to its title. Otherwise, Juncker’s fairness is one directed towards a general category of (tax-paying and law-abiding) citizens and the private sector. Specific sections of society, such as that of labourers, which will become the focus of the FIPC debates, were excluded at this stage.

22

On his appointment letter to Ansip, Juncker mentioned fairness just once regarding the need for a ‘fair level-playing field for all companies offering their goods and services on-line and in digital form’. [32] Juncker’s letter emphasises a vision to ‘make Europe a world leader in information and communication technology’ through greater harmonisation. [33] Job creation and the development of creative industries would be an effect of this, and to this end the economic language focuses on infrastructure investment and user growth.

23

This language is also reflected in Andrus Ansip’s blog, which until September 2017 hosted 79 posts. [34] The posts cover topics including the progress of the Digital Single Market team activities, issues around internet safety and trust, infrastructure, start-ups and internet skills, international relations and in less measure gender equality, cultural diversity, research, education and health. To Juncker’s distant, generalising, category of citizen, Ansip has added some consideration of the vulnerable, such as children, the elderly and ill, as well as unemployed youth. Women in the context of gender balance are also addressed. Amongst the private sector, the broadcasting, telecoms and media sectors are the ones singled out. Between these citizens and the private sector lies the much talked about start-up environment, which is expected to bring innovation. Entrepreneurship is thus supported, whilst employment is not deemed worthy of mentioning.

24

‘Fairness’ does not appear in the posts’ headings, but it is mentioned occasionally within posts. A trawl of 30 posts shows the concept of fairness used in nine blog posts. However, the strong ideal of fairness promoted by Juncker in a remote and unspecified manner, becomes diluted in Ansip’s informal voicings and continues to be very much focussed on the general citizen and competition rules between corporations. ‘Fair remuneration for artists’ as the FIPC would have it, starts to gain traction by the end of 2015 in two of Ansip’s blogposts. One of them carries the phrase in the title of this article (‘We want artists to be fully and fairly paid for their work’) and makes an additional case for ‘an internet with fair and equal access’. [35] With a similar but more compelling tone is a guest blog by Tibor Navraciscs, the Commissioner responsible for Education, Culture, Youth and Sport, in which he makes a nuanced case for the ‘fair remuneration for creators and for everyone who is part of the value chain’, talking about the need to remunerate fairly the seven million people employed by the cultural and creative industries. [36] But these are the exceptions to the rule in a series of posts focussed on entrepreneurship and corporations, whilst disengaged from the realities of the majority of digital service creators and users.

25

Responding to Juncker’s intention to modernise copyright rules, and without much certainty of how this intention would be exercised, [37] the Parliament appointed Julia Reda to report on the implementation of the last major copyright overhaul, the InfoSoc Directive. A German Pirate Party representative with the Green-EFA, Reda is the only Pirate Party MEP in the current 2014-19 parliament. Strongly in favour of open knowledge, on her election day she vowed to work towards a European Copyright Reform. [38]

26

In her draft report published in January 2015, Reda recommended the EU-wide harmonisation of copyright exceptions through four main principles: use of a more open norm based on the Berne Convention’s three-step-test; a reduction in term length; broad exceptions for educational purposes, and a simplification of the over-complex current rules. [39] Of relevance to the present case study is her recommendation to strengthen the bargaining power of authors and performers in contracts with other rightsholders and intermediaries. [40] Notably, her two uses of fairness relate to rules benefitting the general public. [41] This changes in the report adopted by the Parliament in June of the same year, where the simplicity and elegance of Reda’s draft report is replaced by a more complex and lengthy report that reflects the hard work of corporations in influencing Parliament over the preceding period.

27

Note that the FIPC was launched officially in May 2015. [42] Although performers had voiced similar intentions for about a decade, the current form of the campaign was launched ahead of the parliamentary vote on this report. It is significant that it is at this point that the concept of ‘fair remuneration’ enters the mainstream of the copyright debate.

28

The word ‘fair’ appears in the final report a total of 12 times, of which ten refer explicitly to fair remuneration or compensation. [43] The repeated use of the ‘fair remuneration’ phrase should be good news for the FIPC, especially the points addressing, first, the creation of contractual mechanisms for the regulation of what are considered to be unbalanced contractual relations [44] and, second, the intention to create parity in remuneration between the digital and analogue worlds. [45] The remaining points are likely to be more beneficial to rightsholders, which are more often than not the assignees of authors and performers. All in all, the careful language of the report, providing for all the parties, suggests that the balance could still tip in favour of any of the parties. But with the precedent set by the Commission’s language focussed on corporations and entrepreneurs, the group behind the FIPC still has a lot of work to do at this point.

29

The European Commission’s Proposal for a Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (henceforth the EC Proposal) was published on 14th September 2016. [46] Although much change is expected at this stage and some flexibility is built into it, the EC Proposal provides the structural framework for the Parliament and Council to work with. That is, the proposed amendments are drafted strictly in response to the EC Proposal and conforming to its structure.

30

The 33-page Proposal is pre-empted by an Explanatory Memorandum (11 pages), and the main body consists of Recitals (setting out the context for the articles taking into account their interpretation), and five Titles. The core of the Proposal is in the three middle Titles: Measures to adapt exceptions and limitations to the digital and cross-border environment (Title II); Measures to improve licensing practices and ensure wider access to content (Title III); and Measures to achieve a well-functioning marketplace for copyright (Title IV). This last one is composed of six articles in three chapters. Two titles carry the word ‘fair’: Article 12 ‘Claims to fair compensation’ refers to the sharing of compensation from copying between authors and publishers. Chapter 3 is entitled ‘Fair remuneration in contracts of authors and performers’. It is the core package granted to authors and performers and hence the focus of the attention of the FIPC.

31

The transparency obligation under article 14 provides that authors and performers are duly informed of the specificities of the exploitation of their works and performances by their contractual counterparts. This article formalises voluntary transparency statements already in place world-wide, such as the Fair Digital Deals Declaration proposed and subscribed to by the World Independent Network (WIN) [47] and the subsequent Code of Conduct for the French Music Industry. [48] Article 14 has thus been welcomed by authors and performers as well as by the few independent record companies that have subscribed to such statements. However, considering that current technological developments offer inexpensive tools to warrant transparency for all the relevant parties, the article is unnecessarily limited by paragraphs (2) and (3). These make the obligation subject to, first, a proportionality assessment between the value of the revenue and the administrative burden resulting from the obligation and, second, the ‘significance of the contribution’ to the overall work or performance. By limiting the obligation in this way, Article 14 of the EC proposal would benefit only a minority of high profile authors and performers. [49]

32

The contract adjustment mechanism under article 15 of the EC Proposal offers authors and performers the possibility of adjusting a contract they entered into when their bargaining power was low, so that the new terms offer them appropriate remuneration commensurate with subsequent success. The article thus acknowledges that authors’ and performers’ low revenue level may be linked to unfair contractual terms and, in this sense, it has been welcomed by these stakeholders.

33

However, the article has been subject to considerable controversy. From the perspective of authors and performers, it does not acknowledge the complexities of bringing such a claim to contractual counterparts with greater bargaining power (such as publishers, record companies and other commercial intermediaries). These include the high cost of engaging in such a dispute and the risk of compromising future engagements. From the perspective of record companies, the breadth of the wording represents contractual uncertainty. They argue that this is because investment in new artists involves large advances and promotion costs, which depend on a rise in ‘revenues and benefits derived from the exploitation of the works or performances’ in order to be recouped. [50] Also, record companies make the point that the profits from successful artists largely get reinvested in new ones that may not be as successful. This means that, if every successful artist gets paid the maximum possible share from the revenues from their recordings, investment in new acts will be reduced.

34

Article 16 of the EC proposal provides for the creation of a voluntary, alternative dispute resolution procedure for disputes related to obligations arising from articles 14 and 15. Such a procedure is generally preferred over litigation, but there are questions about who would preside over such a procedure.

35

In Chapter 3, the concept of ‘fairness’ in relation to authors and performers is put to the test. Instead of responding to the FIPC, Chapter 3 focusses on balancing the bargaining power between the parties to a contract, that is, authors and performers on the one hand, and corporations on the other. This outcome acknowledges a fundamental imbalance in contractual power relations. However, in seeking to also balance all of the stakeholders’ interests in the copyright reform process, the EC proposal falls short of addressing the contractual imbalance. As I describe below, it is here that competing notions of ‘fairness’ begin to stand out.

36

Section 5.4 of the Impact Assessment (IA) produced by the European Commission to accompany the EC Proposal gives details about the reasoning behind the implementation of Articles 14-16. [51] According to the Public Consultation and other documents produced by campaigners, authors and performers face a lack of transparency in their contractual relationships in relation to the type of exploitation of their works and performances and amounts owed. [52] The IA responded to this by stating that ‘the main underlying cause of this problem is related to a market failure: there is a natural imbalance in bargaining power in the contractual relationships favouring the counterparty of the creator, partly due to the existing information asymmetry’. [53] To address this problem, the IA considers three options, of which the EC chose the third and most comprehensive, that is, articles 14-16.

37

The debate that ensues reveals details about the lively lobbying process surrounding the European Commission’s work. This is recorded in the footnotes and reference literature which itself bears titles containing the word fairness. So, for example, footnote 529 references the Creators’ Rights Alliance, an umbrella organisation for authors and performers throughout the media sector. [54] Similarly, footnotes 542, 558 and 562 make reference to the Public Consultation results, which mention ‘a lack of “adequate or fair remuneration”’, [55] call for a ‘healthy competition to ensure fair remuneration for creators’ [56] and state that ‘a buy-out contract prevents [creators’] adequate or fair remuneration’. [57]

38

The only mention of the FIPC requests appears in this discussion under Option 2 (Imposing transparency obligations on the contractual counterparties of creators), where creators are described as strongly supporting ‘transparency obligations leading to appropriate solutions per sector’. [58] The IA adds: ‘Some would however claim that transparency obligations on their own are not sufficient and would call for further intervention on unfair contracts or the introduction of an unwaivable remuneration right’. [59] Footnote 557 expands on this, explaining that some stakeholders claim that ‘an unwaivable right for remuneration is necessary to ensure a minimum appropriate remuneration to creators’, and referencing the Society of Audiovisual Authors’ White Paper and the FIPC. [60]

39

Much has happened since Juncker’s initial use of the word ‘fairness’, where it was mentioned in a manner disengaged from the specificities of his large constituency but promoting a ‘fair playing field’ for the companies involved in the production of digital services. In the context of the copyright reform within the project of the Digital Single Market, ‘fairness’ has received more attention as spelled out by the different actors. Fairness is now related to the remuneration of authors and performers, specifically meaning ‘a more balanced playing field in contractual relations between authors and performers and their contractual counterparts’. Meanwhile, the meaning given by the FIPC—for which fairness translates as ‘the introduction of an unwaivable equitable remuneration right’—has not yet garnered support. Most significantly, reading through the effect of Articles 14-16 on authors and performers, Juncker’s intention of ensuring fairness amongst corporations remains intact. I now turn to a more nuanced examination of specific stakeholder perspectives.

40

The study is based on 15 one-hour interviews, which were conducted between 2016 and 2017 in London and Brussels. Interviewees represented nine stakeholder groups, two political parties, and the position of one European civil servant. I note that the limited number of interviewees does not reflect the potential views of the entirety of the affected population. Rather, I have taken great care in talking to high-level representatives of UK trade associations, including CEOs or Policy Affairs officials holding the views that are most likely to find their way to EU policy-makers. In order to give further resonance to the interviews, I have combined these with extensive fieldwork at record industry and government events as both an observer and a participant, and with primary literature including online resources from stakeholder websites, the European Commission and Parliament websites, news websites, and social media.

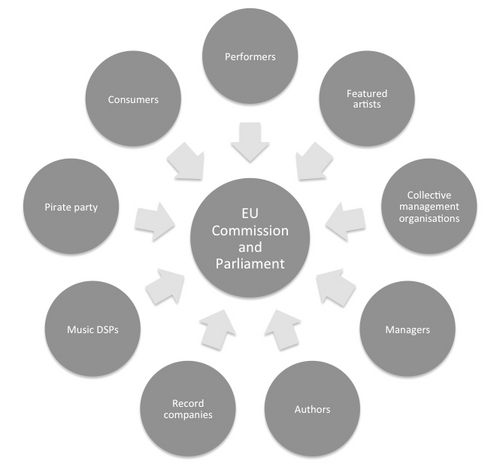

Figure 1: Choice of stakeholders

41

The choice of stakeholder groups is summarised in Figure 1 and was sought to represent a wide range of stakeholders both favourable and not-so-favourable to the FIPC. I have organised stakeholders starting from those participating in the FIPC (performers, featured artists, CMOs), moving on to those favourable but not officially involved in the campaign (managers and authors), then introducing those opposed to it (record companies and DSPs), and finalising with those who are traditionally left out of the debate but who also have important stakes in it (Pirate Party and consumers, who closing the circle, again are likely to support the campaign).

42

With the skilful support of research assistant Adrian Aronsson-Storrier, I designed an interview schedule for each individual respondent touching on the following themes: overview of the campaign; relevance of articles 14-16 of the EC’s Proposal; and lobbying practices in the UK and Europe. I structured each schedule around these themes bearing in mind individual interests and priorities, and also gave respondents the flexibility to respond in their own time and lead me in unexpected directions. I have anonymised the interviews to allow respondents to talk freely without potentially harming their careers. I took notes during the interviews and prepared field notes describing my overall impression of the respondents and interview conditions. Through immersion in these combined sources, the concept of fairness began to emerge as a leading theme in copyright debates.

43

The legal term ‘performers’ is a broad one, encompassing what the industry would call orchestral musicians (whether freelance or employed), session musicians (whether for live, recording, film or TV session work), featured artists (signed to major or indie labels) and self-releasing artists. While each group has distinctive features, most of them overlap with each other, with performers taking different roles throughout their careers. These distinctions amongst performers are not reflected in the UK or EU copyright systems but are important within the industry. As I discuss below, the different groups of performers often represent conflicting interests which come to the fore in situations like the one described here, where legislative reform is at stake.

44

For lack of a better term, I will use ‘performers’ to describe the first two groups: orchestral and session musicians. This may be confusing at times but acknowledges the fact that these musicians represent the great majority of performers. In the UK, performers are typically represented by the Musicians’ Union (MU), founded in 1893. The MU has a membership of 30,000 musicians, who were described by an interviewee as representing ‘the musical labour force’. [61] While some of them may be well known within the industry, they may be less well-known by the general public.

45

According to the campaign documents [62] and interviews, [63] performers’ associations believe that all performers deserve royalties. They argue that due to contracting practices that buy performers out of their rights, performers need an unwaivable ER right. In other words, by implementing the new ER right, the campaign ultimately seeks to address the performers’ lack of bargaining power. For performers, therefore, a ‘fair internet’ is one that remunerates performers collectively for making available their music online for on-demand use of their recorded performances, regardless of contractual agreement. Their incentive is economic based on lack of bargaining power.

46

Under this term I group together featured artists and self-releasing artists. Featured artists are those who are featured on album sleeves and promotional material and are often signed by indie or major labels. As noted above, under UK and EU copyright law, featured artists and self-releasing artists are still performers, but in industry practice they fulfil different roles and might represent different interests.

47

Most featured artists sign contracts that may be more advantageous than those signed by the majority of performers, but that may still not be in their favour. These may include a small percentage of royalties tied to conditions such as the infamous packaging and breakage deductions even on digital income. [64] A small minority of featured artists—the most famous ones—have enough bargaining power to negotiate with their powerful counterparts a contract that will benefit them in the long term. Self-releasing artists take care of the entire process themselves and so do not need to enter into contracts, unless by choice and when it is in their favour. This group encompasses very famous artists who were launched to fame by a major label and then became independent, like Radiohead, or well- and not-so-well-known DIY artists who manage the entire process with the help of sub-contractors, like Imogen Heap [65] and Amanda Palmer. [66]

48

Regarding the FIPC, there are differences in opinion between, on the one hand, the large majority of featured artists in less favourable contracts and, on the other, the small, but influential, minority of featured artists in favourable contracts and successful self-releasing artists. The first group supports the FIPC under the same argument offered by performers.

49

The second group understandably has its reservations: firstly, collectively managed rights, such as this right would become, have administration costs that they may not be willing to pay. Secondly, featured artists would see themselves in a situation where they would have to share their revenue with session musicians, which they do not do at the moment. Thirdly, if the unwaivable ER right is introduced instead of the exclusive right (and not alongside this right), then they would lose the opportunity to negotiate the value of that right, that is, they would lose bargaining power vis-à-vis powerful record companies. This case illustrates Kretschmer and Kawohl’s observation that the most successful artists tend to align their interests with investor interests—in this case with record companies. [67] This explains why these artists are happy to campaign alongside and represent the interests of power record companies. In a winner-take-all market, ‘they benefit disproportionately from the current copyright system’. [68] Because the incentive of highly successful artists is economic, relative bargaining power has to be assessed carefully.

50

In the UK, the body representing this conflicting group is the Featured Artist Coalition (FAC), a small association if compared with the MU, founded in 2009. As a key member of the International Organisation for Artists, the FAC publicly supports the FIPC. This was not without some internal tension, though.

Exclusive rights are only stronger and better in an efficient market. Music is not an efficient marketplace and, therefore, the security of compensation through remuneration rights at a lower level is more attractive to most artists than the ability to exploit and negotiate individually on their exclusive rights. So, for me, even if the Fair Internet Campaign had been successful, you would hope, in an ever-improving market, if digital lives up to its vision of transparency and the ability to actually see what’s going on, you would expect those arrangements to be transitional in some sense, because, ultimately, the cost-effectiveness direct… [sic] and, you know, to do better, more commercial deals at lower costs, with exclusive rights, that we have more control over, should be better. So, it depends again, on the timescale you’re looking at. [69]

51

The hesitation above refers to the cost-effectiveness of the management of rights as this interviewee explained later:

If you do business through a CMO, you’re accepting that you’re going to pay a lot of costs, yeah, and in the UK, we’re very lucky that our CMO is quite transparent. […] Now, I’m going to say something quite contradictory really, in a sense, because, on the one hand, okay, so because of the lack of transparency, I’d rather have secure revenue than no revenue, so I’d rather have revenue with significant costs deducted that I know I can count on, than allow myself to be ripped off all the time. [70]

52

This view is a complex one which combines digital technology with transparency, transparency with the relative cost-effectiveness of exclusive and ER rights, and this in turn with different timescales. This bringing together of multiple perspectives and possibilities ultimately reflects the unique position of featured artists. However, as a representative body, the FAC takes the same view as the MU: a ‘fair internet for creators’ is one that remunerates artists for making their music available online.

53

In the UK, license fees for performers are paid by record companies and are collected by the CMO in charge of collecting license fees on behalf of record companies. This is PPL, a CMO set up by record companies. Although over the years performers have increased their say over how PPL is run, [71] idiosyncrasies related to this history remain. For example, PPL is not part of AEPO-Artis, the European association of performers’ collective management organisations and is therefore not part of the FIPC. The CMOs that are part of AEPO-Artis have different histories that involve representation of performers, in the same way that musicians’ unions across the world represent the interests of performers. In this role, AEPO-Artis is acutely aware of performers’ lack of bargaining power. [72]

54

However, it could be argued that CMOs have an additional interest in collecting license fees, as they get to keep a percentage fee to cover running costs which will grow with the management of additional rights. Or as one interviewee put it: ‘if you have a bunch of collecting societies sitting round a table and you ask what the answer should be, the answer is collective management, irrespective of the question’. [73] For these reasons, it makes sense that performer CMOs are behind the FIPC. For performer CMOs a ‘fair internet for creators’ is therefore one that provides a collectively managed solution for remunerating artists for making their music available online. Their incentive is the economic well-being of performers and is based on their members’ lack of bargaining power.

55

Managers represent performers and artists and, in doing so, receive a cut of their income. Managers are therefore generally sympathetic to performers’ and featured artists’ causes. However, considering that there are split views between these two groups regarding the FIPC’s proposals - their representative body in the UK - the Music Managers Forum (MMF), is ambivalent. Although not officially part of the FIPC, the MMF endorses the campaign’s ideals but does so from the sidelines: ‘we’ve supported the FAC’s supporting it’. [74]

56

The Digital Dollar Reports I and II commissioned by the MMF clearly make the case for the two groups, but ultimately they remain inconclusive. [75] However, these reports make it absolutely clear that contracts offered by major and some indie labels are exploitative. Their idea of fairness is a situation whereby this power imbalance is addressed, whether through greater transparency, contract adjustment mechanisms by which inexperienced artists turned famous become legally entitled to change the terms of their contracts, or ER rights. Their incentive is therefore economic, considering relative bargaining power.

57

Music authors and performers have historically diverged over copyright matters. Authors see income deriving from performers’ rights as diminishing their own. Yet under the EU proposal, authors and performers of all stripes have been bundled together under Chapter 3 of Title II. [76] Some cross-sectoral campaigns do exist, such as the UK Creators’ Rights Alliance, under which authors and performers have jointly campaigned for a more level playing field vis-à-vis powerful contractors, including publishers, record companies and DSPs. This is the Fair Terms for Creators Campaign currently lobbying the EU government, of which the MU is a signatory, but the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors (BASCA) is not.

58

During this particular reform process, authors have sided with record companies to campaign against the value gap and for payment from DSPs protected under safe harbour rules, such as YouTube. This is because if successful, authors would be remunerated for making their works available online through their CMO, the Performing Rights Society (PRS), as they are by other commercial DSPs like Spotify. Since performers do not receive royalties from any DSP (the reason for the FIPC, in the first place), performers have decided to make sure they are first remunerated for on-demand services, before fighting a behemoth like YouTube, especially considering that YouTube offers alternative payment methods for artists.

59

In 2016, music authors and performers in the UK decided to overcome their differences and make some steps towards mutually supporting each other’s campaigns. Under the rationale that they should be working together against much greater powers, they have formed the Council of Music Makers. It may be through efforts such as this that some parliamentary committees have been more favourable towards the collectively managed solution proposed by the FIPC. As explained to me by a respondent from within the EC, legislators do like to see cross-sectoral agreement. [77] The surprise is that the equitable remuneration right applies now to both authors and performers. And both authors and performers have expressed some concern about this for the reasons outlined above, namely that it could weaken authors’ exclusive rights. For authors a ‘fair internet for creators’ is one in which authors can retain the highest possible income, even if that means siding with the weaker side for political support. Their immediate incentive is strategic, whilst their long-term incentive is economic, so their relative bargaining power has to be assessed carefully.

60

In terms of attitude towards performers, I have not found any significant divergences between indie and major labels. The general view here is that some performers deserve royalties, that is, featured artists. For session musicians, a buy-out is sufficient. One industry representative naturalised this position: ‘The nature of the performance of session musicians is that it is a buy-out of the exclusive rights. Obviously what they're paid allows for that, that's simply the nature of the work they do’. [78] Another put this in terms of justice:

Session musicians, and let’s be clear, we have an agreement with session musicians that pays them for playing of tracks, and you know, we pay them for a job, in the same way you pay anyone else. [Laughter]. Now, on broadcast, they happen to get a repeat fee, but there’s no, kind of, theoretical, there’s no kind of justice reason why someone who you pay to do something should then get paid again and again, and again and again. […] They’re paid per session, that’s how it works, in the same way that if you go to an orchestra and you play for an evening, you’re paid. [79]

61

The comparison of a recording with a live performance is remarkable, considering that it is thanks to license fees for secondary use that record companies have become so powerful. In short, record companies are happy to negotiate with successful featured artists but do not want to entertain the possibility of royalty payments for performers, as that would diminish their wealth. For record companies a ‘fair internet for creators’ is therefore one that retains the status quo: record companies are incentivised by economic gains and by ensuring current levels of bargaining power.

62

2016 marked the year when digital streaming started to be profitable. [80] This stood in contrast to years of investment in a technology that has been charged with saving the record industry from its post-Napster crisis. In subscription models, the aim of DSPs is to retain a percentage, typically of 30 per cent, of their total income and redistribute the remaining income to music rightsholders. However, DSPs have persuaded investors that this model works best after a certain number of subscribers has been achieved. Anything below that number initiates losses, which is precisely what has happened in the last few years since DSPs started to populate the market. Understandably then, DSPs are not keen on additional outgoings. Considering also that DSPs have received funding from powerful investors over this period, many of which are music rightsholders themselves, a restructuring of their outgoings would not be welcome either. Their argument turns the FIPC on its head: if DSPs have further outgoings, they will have to close down, in which case all musicians would lose, regardless of relative bargaining power. [81] This argument resonates with the EC, to the point that my Commission respondent repeated it almost verbatim. [82] For DSPs, like for record companies, a ‘fair internet for creators’ is therefore one that retains the status quo.

63

The first Pirate Party was established in Sweden in 2006 and the label has spread across several countries since. They are known for supporting civil rights, direct democracy, open access to knowledge, and privacy. Strong supporters of copyright reform, pirate parties have end-users as their primary beneficiaries. During a brief informal conversation with the only Pirate Party MEP, Julia Reda, on 24th June 2016, she disagreed in principle with unwaivable collectively managed rights. Her view was that authors and performers should be able to decide whether they want any money at all.

64

Here the incentive is not economic, but ideological: creators supporting open access should be able to do so without ifs and buts. In other words, by removing decision-making, ERs (whether MA or communication to the public rights) effectively remove creators’ bargaining power vis-à-vis open access. Thus, a ‘fair internet for creators’ is one that preserves creators’ freedom to either monetise or share their creations for free. Albeit an argument with little resonance in the industry and consumers (see below), Julia Reda, as member of the committee of legal affairs (JURI), was the copyright reform rapporteur and thus has had some influence over the process.

65

The 2014 Report on the Responses to the Public Consultation portrays consumers as favourable towards authors and performers. [83] Consumers are aware that ‘many contracts for the exploitation of works were concluded before the emergence of digital content distribution, hence they do not explicitly provide for royalties for online exploitation’. [84] They further point out that ‘the way in which new online streaming services are licensed may circumvent the payment of digital royalties to artists and hence contravene the aim of ensuring appropriate remuneration for creators and right holders in the digital world’. [85] Consumers therefore support EU intervention in this area, mainly in the form of contractual mechanisms that would allow authors and performers to retain some control over their works.

66

In May 2017, I attended a workshop conducted by AEPO-Artis in Brussels in which Isabelle Buschke, Head of Office of the Federation of German Consumer Organisations, came to the support of the FIPC. Her main agenda was the creation of a levy system, whereby consumers would pay a fee to access all creative products online, which would then be redistributed to the different industries. By overcoming the complexity inherent in individual DSP payment systems, she argued, a levy system would introduce the simplicity needed to bring down piracy and close the value gap - two of the greatest problems faced by record companies. However, in order to close the value gap, Buschke called for reassurance that the money was passed on to the creators. This would involve payments by DSPs collectively managed by CMOs. Her view was that consumers would be happier to pay for artistic products if they knew that artists were well remunerated. Therefore, for consumer associations, a ‘fairer internet for creators’ is one that remunerates creators for their investment in musical works and performances and the proposal put forward by the FIPC is one that they feel they can support. The incentive is economic in the sense that they seek the long-term well-being of the creative ecosystem. They support the FIPC because it would inch closer to re-establishing a balance in bargaining power.

67

The different positions can be summarised in three groups. For the groups most favourable to the FIPC, fairness is synonymous with ‘the introduction of an unwaivable equitable remuneration right’ based on the perception that performers are in a very low bargaining position (performers, less successful featured artists and their managers, performer CMOs and consumers). On the other side of the fence are those groups that consider fairness to be synonymous with retaining the status quo relative to the FIPC. These include those with the highest bargaining power (record companies and highly successful featured artists) and those who worry about the quantity and source of payment allocated to performers (as well as record companies and highly successful featured artists, authors and DSPs). The exception to these two groups is the argument put forward by the Pirate Party, for whom fairness translates into the creators’ freedom to monetise or freely share their creations. The incentive is ideological: to retain individual freedom to decide over the collective benefit of copyright.

68

I now examine how these views have been received and reproduced by the Parliament.

69

After its release in August 2016, the EC Proposal moved on to be scrutinised in Parliament. In the legislative process, the Parliament is responsible for proposing amendments to the initial proposal and negotiating these with the Council. During this time, trade associations and lobbying groups are busy making their views about the EC Proposal heard in Parliament and the amendments reflect this. The first set of amendments proposed in April 2017, finally brought good news to the FIPC, with some of the amendments sympathetic to its cause.

70

In the context of the EU copyright reform, the Legal Affairs Committee (JURI) has taken a leading role in amending the EC Proposal. This involves drafting a report that serves as a first critical reflection on the EC draft proposal [86] and by requesting opinions from other committees. The committees that have been asked for opinions are: Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO) [87] ; Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE); [88] Culture and Education (CULT), [89] and most recently, Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE). [90] The adopted opinions of IMCO, ITRE and CULT contain nearly 1000 amendments. Among these amendments there are only a few devoted to Articles 14-16.

71

IMCO focuses its efforts on limiting the controversial proportionality assessment designed to eliminate the obligation of offering transparency to those earning the least. For the majority of authors and performers in a weak bargaining position, this is good news. For this group, IMCO has re-established some sense of fairness by offering greater transparency and thus balancing the bargaining power of the different contractual parties.

72

The best news for the FIPC comes in the form of the new Art.14a by ITRE [91] and CULT: [92] both committees offer an equitable remuneration right for authors and performers in addition to the exclusive making available right. While both articles 14a bear the same title (Unwaivable right to fair remuneration for authors and performers), only ITRE’s proposal is fully unwaivable. In contrast, CULT’s allows EU member states to proscribe the waiving of the right [93] and creates two scenarios under which the right can be waived. [94] The second simply provides a mechanism for contractors to turn it into a waivable right. However, the first scenario interestingly responds to Reda’s concern regarding the clashing of unwaivable rights with open access provisions. It does this by allowing an author or performer to ‘grant a free non-exclusive right for the benefit of all users for the use of his or her work’. [95] Finally note that, unlike the wording of the FIPC’s suggested amendments, the addition of Art.14a, includes authors as well as performers, leaving authors with a question mark over the effect of this right on their bargaining power.

73

ITRE’s new Art.15a [96] regarding a reversion right under extreme negligence represents a thoughtful start, but it still imposes many conditions on authors and performers to extract themselves from their contracts. Regarding Art.16, both ITRE and CULT [97] offer provisions to level the playing field when using the alternative dispute mechanism, such as third-party representation (CULT and ITRE) and anonymity (ITRE). CULT also provides that ‘the costs directly linked to the procedure should be affordable’. [98]

74

A combination of the three sets of amendments would give authors and performers the greatest assurances in terms of strengthening their bargaining power. With these combined changes the intention of providing fairness, understood as ‘a more balanced playing field in contractual relations between authors and performers and their contractual counterparts’, is the closest to a real action. However, it is doubtful that the three sets of amendments will merge in this idealised way. Amongst the three, ITRE represents the interests of authors and performers more strongly, while counter-intuitively, CULT appears more cautious of stepping on the major players’ footsteps. [99]

75

All in all, the FIPC has taken some hold, despite the main obstacles remaining the same: the record companies’ resistance; the uncertainty of DSPs but also record companies and authors over quantity and source of payment, and from the European Commission’s perspective, the long-term balance of interests. Yet considering that some opinions included the FIPC’s proposal, the campaigners have some reason for hope.

76

By April 2018, the Legal Affairs Committee had provisionally scheduled the vote on their report for June 2018, a date that has been moving for almost a year. This vote then needs to be confirmed by the entire Parliament, which means that some form of consensus should ideally be reached with the Council by then. Discussion on the Council’s proposals have been underway; but given the delays, the regular six-monthly change of Council Presidency brings new challenges. In order to retain the relevant amendments, FIPC will need to work a lot harder with MEPs and each of the countries’ Council Ministers.

77

With David Harvey’s A Brief History of Neoliberalism in mind, the process described here, as well as the choice of words employed by the parties, reads like a case sample of neoliberal forces at work. [100] Neoliberalism, according to the author, is a political economic theory that holds that ‘human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade’. [101] In line with this theory, the role of the state is not only to preserve an institutional framework appropriate to such practices, but also to create it, ‘by state action if necessary’. [102]

78

Taking hold since the 1970s, neoliberal thought has become the hegemonic mode of discourse, permeating what we perceive to be common sense. In its hijack of the concept of individual freedom, neoliberal thought is appealing. Yet the assumption that individual freedoms are guaranteed by freedom of the market is misleading. As Harvey points out, values of individual freedom and social justice are not necessarily compatible: ‘Pursuit of social justice presupposes social solidarities and a willingness to submerge individual wants, needs, and desires in the cause of some more general struggle for, say, social equality or environmental justice’. [103] While these differences can be bridged, Harvey continues, in neoliberal rhetoric ‘all forms of social solidarity were to be dissolved in favour of individualism, private property, personal responsibility, and family values’, ultimately benefitting a small capitalist or entrepreneurial class at the expense of a much larger labouring class. [104]

79

By emphasizing the significance of contractual relations in the marketplace, neoliberalism:

holds that the social good will be maximized by maximizing reach and frequency of market transactions, and it seeks to bring all human action into the domain of the market. This requires technologies of information creation and capacities to accumulate, store, transfer, analyse, and use massive databases to guide decisions in the global marketplace. […] These technologies have compressed the rising density of market transactions in both space and time. They have produced a particularly intensive burst of […] ‘time-space compression’. The greater the geographical range and the shorter the term of market contracts the better. [105]

80

This is the political economic environment sought by Juncker and the European Commission via Ansip and his ‘Digital Single Market’ project. Entrepreneurs are at the centre of this strategy, that mostly ignores any other characterisation of Europe’s citizens. Seen in this light, Articles 14-16 of the EC Proposal make perfect sense in addressing a problem of bargaining power: the need to establish better information (transparency) and an environment that optimises market transactions. By regulating contracts, the state interferes at the point where individuals meet to transact and avoids drawing in any sense of collectivity (and with it social justice), as is suggested by the FIPC. As one of my interviewees pointed out:

The idea of a right to transparency, a right to renegotiate and an independent alternative dispute resolution mechanism caused a direct response by the Commission to try and help find something for performance that was market-driven, would not conflict with the right to give the freedom to contract and that would show their political and emotional commitment to artists in Europe, despite the inability to support the Fair Internet Campaign. [106]

81

It is understandable that record companies are against any proposition that may compromise their ability to increase their wealth. They oppose adding administrative burdens as proposed by the FIPC and mechanisms that remove contractual certainty as currently suggested by Articles 14-16. As members of Harvey’s capitalist class and the driving force behind neoliberal ideology, record companies have invested considerable capital in shaping copyright the way it is and so will defend the status quo. Their aim in this reform process is to extract wealth from those digital service providers operating outside the realms of their long-established licensing mechanisms, notably YouTube (as suggested by Recital 38 and Article 13 of the EC Proposal, not the focus of this paper). But the idea that they might well share potential proceeds with the labour force behind their products—the creators and content producers—is not one that they want to entertain. As Thomas Edsall has explained:

During the 1970s, business refined its ability to act as a class, submerging competitive instincts in favour of joint, cooperative action in the legislative arena. Rather than individual companies seeking only special favours […] the dominant theme in the political strategy of business became a shared interest in bills such as consumer protection and labour law reform, and in the enactment of favourable tax, regulatory and antitrust regulation. [107]

82

The position of the most successful artists towards the FIPC is consistent with this. As Kretschmer and Kawohl have shown, when artists arrive at a point where they have level bargaining power, they coincide with the ideal neoliberal market conditions: a situation where a zero-cost transaction is determined solely by market signals. [108] Collective agreements would get in the way of this by adding complexity to the transaction and the intrinsic costs of managing and distributing payments to a collectivity they have only just surpassed. The cost of these transactions, insignificant in light of the wealth they extract from their exclusive rights, is too high a price to pay for others’ potential benefit. The neoliberal definition of individual freedom supports this view and makes it perfectly acceptable in public opinion. In contrast with record companies, however, I can see no reason why successful artists would oppose Articles 14-16.

83

Reda’s argument on the other hand, draws attention to the fact that copyright is an opt-out system: every original creation is automatically protected by copyright—and thus drawn into the market system—without the need for registration. However, authors and performers are free to assert their wish to opt-out of their rights and make their creations freely available to the public. An unwaivable right such as that proposed by the FIPC, would stop creators from opting out, and would demand that every use was licensed by collective management organisations. The resistance to the unwaivable right, in the name of a small minority who might opt out, upholds the individual freedom to oppose imposed market transactions and thus to benefit the wider public by granting it open access to knowledge. It is a view with a long-term commitment to the ideological imperative of open knowledge that does not, however, overturn the copyright regime. Articles 14-16 address creators’ challenges with bargaining power without having to diminish this ideological commitment (even though, as CULT’s amendment 92 proposing Art.14a(2) shows, Reda’s view could also be made compatible with the FIPC’s proposal).

84

Where creators are concerned, as Harvey puts it drawing on Marx, ‘an empty stomach is not conducive to freedom’. [109] So where copyright is the principal, albeit imperfect, mechanism ensuring remuneration from creativity, collective action aiming to restore some of its inherent imbalance might be worth embracing. This is also the understanding reached by consumers, who are willing to pay to overcome this imbalance. The current language of Articles 14-16 is weak (even with the amendments proposed by various parliamentary committees) and is unlikely to address the immediate needs of the majority of performers.

85

The performers’ and consumers’ views overlap with the views of those managers and featured artists that are aware that not all of their constituents fit into the bracket of the highest earners. This overlap of the perspectives of the less powerful stakeholders with consumers suggests that there is a serious power imbalance in the record industry. The oversupply of musicians in a winner-take-all market creates the perfect situation for the exploitation of the less powerful by those in power: the imperative of Harvey’s neoliberal regime.

86

It is this imbalance that the FIPC seeks to address. Yet there is a question mark over whether the FIPC’s proposal alone can reduce an imbalance that has external causes. A slightly better solution is that presented by the ITRE and CULT committees, in which the FIPC’s proposal is offered in addition to Articles 14-16 proposed by the commission. Yet this would add more complexity to an already complex copyright system. In the digital era, whether accepting or rejecting a neoliberal regime, this mounting complexity of the copyright system betrays the system’s inherent deficiencies made explicit by the Pirate Party. Under this rationale, Articles 14-16 with or without the FIPC’s proposal are short-sighted solutions that further sustain the neoliberal regime.

87

The objective of this article was not to determine whether the FIPC is indeed fair in a normative sense. Rather, I have shown how the concept of fairness develops its own self-reinforcing cycles of signification in the process of European copyright reform, drawing attention to how emerging discourses are consistent with hegemonic neo-liberal thought.

88

I started by explaining what the FIPC is, describing the associations behind it and their motivations for engaging in this campaign. I have provided some background for the legal tool demanded by this group and have outlined the advantages of exclusive rights over equitable remuneration rights under perfect market conditions. Considering that the labour market of the record industry can best be described as a winner-take-all market, where bargaining power of the majority of musicians is very low, I have assessed the need for equitable remuneration rights. I then described the general tone of the European Union members regarding fairness in the record industry, by explaining how reform is made and how the copyright reform sits within the wider plan of the current EC presidential cycle. I focussed on EC President Juncker’s vision for his presidency, the Team Leader for Digital Single Market Andrus Ansip’s language employed in his regular blogposts, Julia Reda’s copyright report and, finally, the EC Proposal for a Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market. Analysis of stakeholder views provided further detail on the multiple ways in which the concept of fairness is produced and reproduced in the current process of copyright reform.

89

As I have sought to demonstrate, the concept of fairness is fragmented and very much dependent on the relative bargaining power of stakeholders. However, in considering the vision for a digital single market and, within it, fairness within the record industry, I have identified an overarching conception of fairness held by the European Commission and dominating the discussion that is deeply entrenched in neo-liberal thought. Under this regime, the facilitation of market transactions over ever-increasing geographical areas is expected to benefit entrepreneurs and the already powerful contractual counterparts, but little thought is given to the workers that are hit with increasing casualization and diminishing bargaining power. While the vision held by the European Parliament appears at this stage to be more heterogenous and negotiation with the Council will no doubt add more nuances to it, the framework offered by the European Commission can be taken for granted. In this setting, Rawls’s ideal theory mentioned above serves as a powerful reminder of how far the concept of fairness has been stretched.

90

On 25th May 2018, the Council’s Committee of Permanent Representatives (COREPER) published its common position on the EC proposal. On 20th June 2018, the JURI committee found a common position too. This was at first rejected by the Parliament on 5th July, but after renewed debate, finally approved on 12th September. The process is currently under Trilogue, the closed-door compromise negotiations between the Commission, Parliament and Council. The result of Trilogue needs then to be approved by Parliament for it to become a Directive. This is expected to take place early in 2019. Since the Parliament’s report incorporated the Council’s mandate, no big surprises are expected at this stage.

91

In the Parliament’s version (and not in COREPER’s), Article 14 includes a ‘principle of fair and proportionate remuneration’. Yet the wording is so broad that it adds little to the status quo. Nevertheless, considering that the reform process is still ongoing, FIPC representatives welcomed it with optimism: ‘the vote finally asserted the principle that all performers should be paid a fair and proportional remuneration for all modes of exploitation, including for on-demand uses, and sends a clear signal against persistent and unacceptable buy-out practices’. [110]

92

Paragraph 2 of this new article responds to Reda’s concern regarding the clashing of unwaivable rights with open access provisions, in the event that a Member State might be persuaded to make an equitable remuneration right unwaivable.

93

The transparency obligation of Article 14 has been specified slightly upwards. However, the proportionality assessment proposed by the EC remains (par. 2-3). The amended Article 15 makes it possible for representative organisations to act on the individuals’ behalf, which slightly addresses some of the complexities involved in individuals bringing a case against their powerful counterparts.

94

The bigger news relate to a new Article 16a, the ‘right of revocation’. This gives authors and performers the right to revoke their licensed or transferred rights when their work or performance is not being exploited or reported upon. Like Article 15, this article mainly addresses already powerful featured artists.

95

COREPER’s Article 16a is not in the Parliament’s version. This article strengthens articles 14 and 15 by making unenforceable any contract that does not comply with them.

96

Taken as a package, the so-called ‘transparency triangle’ importantly acknowledges the imbalance of bargaining power between authors and performers and their powerful contractual counterparts. Depending on the balance achieved between its different elements, especially by excluding the proportionality assessment, this set of right has the potential to go some way towards addressing the imbalance between authors and performers and their powerful contractual counterparts. As things stand, not much will be gained.

97

In short, after the parliamentary vote, the conclusions reached in this article still hold: the definition of fairness aligns best with that of entrepreneurs and the already powerful contractual counterparts, and less so with that of the content-creators with the least bargaining power.

My greatest thanks go to the interviewees who gave up their time to speak to me: this research would not have been possible without them. I am also grateful to Adrian Aronsson-Storrier, who assisted me throughout most of the interview stage with dedication and rigour. For inviting me to share my research with students and colleagues, I thank Poorna Mysoor (Intellectual Property Discussion Group, University of Oxford, November 2016), Tom Perchard (Music Research Series, Department of Music, Goldsmiths, University of London, November 2017), and the organisers of the IASPM conference (University of Kassel, June 2017). I also benefitted from thoughtful observations on earlier drafts by John Street, Christina Angelopoulos and one anonymous peer-reviewer.

I gratefully acknowledge The Leverhulme Trust for funding the research conducted for this article.

During the writing up stage, I accepted consulting engagements from the International Federation of Musicians (FIM). This work was unrelated to the Fair Internet for Performers Campaign.

* By Ananay Aguilar, Affiliated Researcher, Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Law (CIPIL), University of Cambridge, email: aa752@cam.ac.uk .

[1] John Rawls, Justice as Fairness: A Restatement (2nd Revised edition edition, Harvard University Press 2001).

[2] ibid 6.1.

[3] ibid 6.2.

[4] ibid 6.4.

[5] John Rawls, The Law of Peoples (Harvard University Press 1999) 89.

[6] Jean-Claude Juncker, ‘A New Start for Europe: My Agenda for Jobs, Growth, Fairness and Democratic Change. Political Guidelines for the next European Commission.’ 6.

[7] Juncker, ‘A New Start for Europe: My Agenda for Jobs, Growth, Fairness and Democratic Change. Political Guidelines for the next European Commission.’

[8] Chris Willman, Interview with Taylor Swift, ‘Exclusive: Taylor Swift on Being Pop’s Instantly Platinum Wonder... And Why She’s Paddling Against the Streams’ (11 June 2014).

[9] Peter Helman, ‘Read Taylor Swift’s Open Letter To Apple Music’ (21 June 2015) https://www.stereogum.com/1810310/ accessed 19 January 2018.

[10] There’s at least one other EU-level campaign using the term ‘fair’ in its title: see https://www.fairtermsforcreators.org/who-we-are.html .

[11] Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (c 48), s.182CA and WIPO Performance and Phonograms Treaty 1996, Art. 10, transposed in the EU via Directive 2001/29/EC, Art. 3 (2a) and implemented in the UK through the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003, Reg. 7.

[12] There’s at least one other EU-level campaign using the term ‘fair’ in its title: see https://www.fairtermsforcreators.org/who-we-are.html .

[13] European Commission, Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on copyright in the Digital Single Market 2016 [2016/0280 (COD)] Articles 14-16.