1

Advertisers are shifting their dollars away from traditional media to digital media. [1] Influencer marketing – the use of opinion leaders such as bloggers with many followers and readers to disseminate product messages – is gaining advertisers’ interest. [2]

2

Advertisers think that influencers, such as bloggers have a considerable impact on their readers – on what they wear, eat, drink, and buy. Moreover, bloggers can reach a large audience and are considered to be trustworthy sources. [3] Therefore, advertisers and social-media-focused agencies approach bloggers to review or promote their brand and products by sending bloggers free products, by promising benefits, or by paying them for writing a review. [4]

3

Thus, blog posts often include product proselyting. Sometimes this expression is the organic, honest opinion of the blogger, other times it is in the service of an advertiser. Therefore, there is a risk of blurring the boundaries between the blogger’s opinion and advertising, misleading readers about the commercial character of a blog, and making it difficult for the reader to discern commercial from non-commercial content. Consumer protection law demands that its commercial nature be adequately disclosed. The disclosure command is intended to help the consumer understand the context of the expression and recognize when blog content is advertising, so they can cope with the message accordingly. [5]

4

In Europe and the US, provisions about unfair commercial practices exist (See Section 5 of the FTC Act and the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive) aiming to protect users from misleading blends of opinion and advertising. These rules have been further interpreted and developed through the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in the US, [6] as well as through case law and self-regulation. [7] In Europe the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive is, moreover, subject to initiatives at the European level to prepare consumer law for the challenges of the digital economy and increasing transparency for consumers on platforms. [8] An important aspect in this context is increased transparency for hidden advertising. [9] In addition, especially in Europe, self-regulation is an important instrument with regards to adding further details and guidance on how to comply with the often very general norms of the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive and can sometimes even go beyond what is required by law. [10]

5

Sponsorship disclosures in blogs can help consumers recognize advertising and change consumers’ responses to sponsored posts. [11] However, little is known about the disclosures that are actually provided in blogs. Gaining insight into the disclosures that are currently used is important, as research has shown that consumers respond differently to different types of disclosures. [12] Insights in the characteristics of disclosures in blog advertising could set the scene for disclosure effect research, providing a framework or typology of disclosures that can be tested for their effectiveness.

6

Therefore, this study 1) presents the law and self-regulative provisions concerning blog advertising both in Europe and the US, and 2) documents the actual practice of disclosing blog advertising: if, and if so how, bloggers disclose influences from advertisers, and how these disclosures align with the regulations in place. We first discuss the codes and regulations addressing social media advertising and the requirement of disclosures in Europe, using The Netherlands as a case study, followed by the US. Second, we describe what is currently known from academic research about the effects of sponsorship disclosures. Third, we introduce and report our content analysis to examine how the regulations are actually put in practice by bloggers.

7

This study is the first to systematically assess blog advertising disclosure and provides an opportunity to advance our knowledge of social media advertising, influencer marketing, and the recent regulations and provisions regarding this phenomenon. To reach the research aims we present a comparison of the regulations regarding blog advertising in the US and Europe, and a content analysis of 200 blog posts stemming from the 40 most popular blogs in the Netherlands and the US. Based on the content analysis, and prior empirical research on the effectiveness of disclosures, we can articulate recommendations for improving regulations. Moreover, the insights of this study provide a valuable foundation for future research investigating the impact of disclosures and can contribute to the development of theories that may explain this impact.

8

The recognizability of advertising is a key element in consumer protection law, in the Netherlands and in Europe. The failure to inform readers about the blogger-brand relationship could constitute a misleading practice under the rules about unfair commercial practices in the Dutch Civil Code. More specifically for the media context, using editorial content to promote products and services without making it clear that a trader has paid for that promotion is also listed on the so-called blacklist of commercial practices. Any practices listed on the blacklist (Annex 1 of the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive) are always considered unfair. Similar prohibitions can be found in e-commerce and media law (for broadcasting and certain video services). [13]

9

It is important to notice, however, that the provisions about unfair commercial practices in principle only apply for the behavior of a trader toward consumers. [14] A “trader” is a person who acts for purposes that relate to his trade or business, or who acts ‘in the name or behalf of a trader”. Bloggers who write a review about a game or book because of purely personal, non-commercial reasons (e.g., because they found it interesting or liked it) will typically not qualify as a trader, with the effect that their practices do not fall under unfair commercial practice law, even if those reviews are, de facto, advertising. There is one exception, however; namely that the blogger who is not acting for his own trade can fall under the provisions regarding unfair commercial practices, especially if he can be considered to “act on behalf of the trader” (Art. 193a (b) Dutch Civil Code, transposing Art. 2(b) of the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive). [15]

10

Also in the Netherlands, advertising self-regulation is playing an important role in providing guidance and adding further details to the legal framework. The Dutch Advertising Code Authority, which is the self-regulatory body for advertising in the Netherlands, provides for example, some additional guidance on the question of when a user can be considered to act on behalf of the trader in its Advertising Code Social Media [16] and stipulates the obligation to inform about instances of social media advertising. The pre-condition is that the blogger has been offered a benefit (which can be a payment but also in natura) and that benefit does actually affect the credibility of the social media message. Being self-regulatory, adherence to the code and its provisions is in principle voluntary. For participating organizations, however, non-compliance of the code can lead to a compliance procedure before the Dutch Advertising Code Authority –thereby adding an additional layer of complaint procedures against irresponsible advertising. In addition, advertising that is non-compliant with the code could also constitute an unfair commercial practice itself. [17] The latter could potentially lead to enforcement actions before the Dutch Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM), which is the regulatory authority that is responsible for monitoring compliance with consumer law and competition law (and certain provisions in data protection law), and that is, among others, tasked with enforcing the rules on unfair commercial practices (and able to impose fines, unlike the Dutch Advertising Code Authority). [18]

11

The code clarifies that professional advertisers as well as bloggers (distributors) can be held responsible for compliance with the provisions in the code. A further amendment in 2017 clarified that that the code also applies to vloggers, and the Data Driven Marketing Association, a self-regulatory instance, issued new guidance on vloggers. [19] What is more, unlike the provisions about unfair commercial practices, this code specifically suggests how bloggers and advertisers can inform consumers about the fact that social media advertising is taking place, for example by stating (translated from Dutch into English) “I received product XXX from brand YYY” or “Brand YYY encouraged me to write this blog.”

12

Interestingly, the code also foresees a specific duty of the advertiser to inform bloggers (distributors) about the relevant provisions and to proactively encourage distributors to obey the rules and act if they fail to do so. Only if the advertiser does so, he can exonerate himself from the failure to comply with the rules. [20] Children below 12 years may not be engaged as vloggers, and advertising (also on social media) that is directed at children must inform children about the commercial character in a way that children can understand. [21]

13

The Social Media Advertising Code is still fairly new (dating from January 2014) and has so far only led to few complaints, some of them directed at the blogger [22] and some at the company. [23] In 2016, the Dutch Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) initiated an investigation into online reviews. The consultation resulted in guidelines that are only directed at companies and marketing service providers in situations where consumers write the reviews for review websites, not individual users that engage in social media advertising. [24]

14

In the US, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) employs a catch-all statute to address problems of unfairness and deception, Section 5 of Federal Trade Commission Act (FTCA). The Act broadly prohibits deceptive trade practices, but leaves these undefined, empowering the FTC to use its expertise and enforcement power to apply the mandate to new circumstances as they arise. [25] The FTCA also broadly prohibits “unfair” trade practices; however, the use of this legal theory is disfavored, and the US is less reliant on a blacklist approach of enumerated unfair acts.

15

The FTC has long held that undisclosed financial connections in seller expression is wrongful. Among the FTC’s first reported cases concerned a vacuum sales company that falsely claimed in advertisements that it was an impartial expert on the devices, when in reality, it had a special arrangement to earn higher profits from two models. [26]

16

Turning to news publications, the FTC issued an advisory opinion in 1968 warning advertisers that clothing commercial messages—even truthful ones—in the garb of news copy was deceptive. [27] With the rise of social media, the FTC began warning both brands and endorsers of disclosure obligations. The FTC investigated a 2014 advertising campaign by Lord & Taylor, a US department store, in which the store paid “fashion influencers” on Instagram to photograph themselves wearing a “Paisley Asymmetrical Dress.” Lord & Taylor settled the case. [28] In September 2017, the FTC settled a case against two social media “influencers” who did not disclose their stake in a gambling website that they promoted through effusive messages, such as “Made $13k in about 5 minutes on [the website] betting. Absolutely insane.” [29]

17

In addition to enforcement actions, the FTC encourages compliance with the FTCA by issuing “Guides” on various marketing and advertising issues. These Guides are opinions—not binding law—of the Commission and notionally they set enforcement priorities and act to warn the private sector about deceptive practices. [30] Thus, the full spectrum of commands included by guides may never have been litigated and upheld by a court. Nonetheless, companies acting in good faith will follow the guides, because a mere investigation by the FTC can cost tens of thousands of dollars in lawyer fees to resolve.

18

Unlike the Dutch Advertising Code, the guidelines are not an instance of self-regulation but rather meant to inform companies on the FTC’s perspective and interpretation of the rules, to enable and promote compliance.

19

The Endorsement Guides were updated in 2016 to also reflect new marketing techniques, such as blogging, native advertising, and social marketing. [31] With an annual budget of just over $300mm, the FTC cannot possibly police all advertising. Thus, the FTC explained that it would not monitor individual bloggers. [32] The FTC left the possibility intact that it could investigate on a case-by-case basis against individual bloggers; however, it did announce that the focus of its investigations would be on the advertiser, not the endorser.

20

As the Endorsement Guides explain, any connection between the endorser and the seller of the advertised product that can “materially affect the weight or credibility of the endorsement” (i.e., the connection is not reasonably expected by the audience) [33] must be fully disclosed. [34] While the FTC illustrates the scope of the code with various examples, it also makes explicit that it does not require specific wording; neither do the Endorsement Guides give any specific guidance regarding the wording of the disclosure. According to the FTC, “What matters is effective communication, not legalese.” [35] That being said, the FTC does provide some suggestions, including formulations such as: “#ad”, “Company X gave me this product to try …” or “Some of the products I’m going to use in this video were sent to me by their manufacturers”. [36]

21

Unlike the Dutch Code, the FTC Endorsement Guides do not speak about concrete responsibilities of advertisers in relation to endorsers. However, in the FAQ document as well as in the examples mentioned in the Endorsement Guides, the FTC does make clear its view that advertisers and intermediaries are responsible for endorsers’ compliance, and therefore, are expected to teach endorsers to adequately disclose their endorsements, and to monitor compliance. [37] A similar line of interpretation has been recently confirmed in one of the few enforcement actions of the Guides in relation to social media advertising thus far. [38]

22

Some self-regulatory codes exist in the US. For example, the Word of Mouth Marketing Association (WOMMA) issued social media disclosure guidelines, [39] which by and large reflect the FTC policies, suggesting a number of possible formats for disclosure. As a piece of self-regulation, compliance with its provisions is voluntary, but to the extent that members bind themselves to such provisions and do not comply, the FTC can investigate and pursue them for deceptive trade practices.

23

Next to the developments in the social media advertising codes and regulations, some empirical studies have looked into the effects of the disclosure of blog advertising. For instance, research showed that, depending on its content, a disclosure of the commercial purpose of a blog can influence the credibility and perceived influence of a blog, the credibility of the blogger, and the attitude toward the message. [40] Revealing the commercial nature of a blog can also reduce readers’ willingness to share the message and purchase intentions of the advertised product. [41] In addition, Campbell, Mohr and Verlegh [42] showed that disclosing advertising in blogs can - depending on the timing - affect consumers’ brand recall and brand attitudes. In the context of recommendations in interpersonal communication, explicitly acknowledging a financial reward for the recommendation (“I am satisfied with the institute, but I am also happy about receiving a reward for my recommendation”) reduced the evaluation of the recommended institute. [43] This effect was only found in communication among strong ties, and therefore could also apply to bloggers and their loyal readership. Furthermore, research has shown that disclosures can increase the recognition of a blog post as advertising, which consequently induces resistance and lowers brand attitudes and purchase intentions of the product reviewed in the blog post. [44] Together these studies indicate that disclosures can empower media users to recognize advertising in blogs and have some (undesirable) effects on responses to blogger, the blog, and the advertised brand or product.

24

But do bloggers actually provide disclosures, and if so how? With respect to this question, only one empirical article exists to our knowledge; Kozinets et al. [45] investigated a “seeding” campaign in which 90 influential bloggers were given a new mobile phone and were encouraged, but not obligated, to blog about it. Although 84% mentioned the phone in their blog, certainly not all of them disclosed their connection to the brand. The researchers conclude that whether and how bloggers disclose their participation depends on the type of blogger and narrative. Whereas some of them emphasized their honesty and not being “bought,” others expressed their disbelief (“I thought it was a scam”) and even defended and authenticated their claims about the phone. Others intentionally concealed their participation in the campaign. This study shows that there is a considerable variation in the use of disclosures, and that certainly not all blog advertising is being disclosed.

25

Despite some evidence for the effects of disclosures and the variation of disclosures, little is known about how often blog posts actually contain advertising, and if and how this advertising is disclosed. Therefore, we propose the first research question:

RQ1: How often do bloggers provide disclosures of advertising?

26

Second, the regulations provide some specific guidelines about the disclosure format. Rules in the Netherlands and in the US require bloggers to disclose any connection to an advertiser. In addition, the Dutch Advertising Code states that a disclosure should explicitly communicate any compensation (in money or in kind) the blogger received from the advertiser. In line with these regulations, empirical research has demonstrated the importance of the explicitness and content of a disclosure. Carr and Hayes [46] found that when the connection with a third party was explicitly disclosed, it positively influenced the perceived credibility of the blogger, making the blog more influential. However, when the disclosure was more implicit, and only hinted at a possible commercial connection between the blogger and the brand, this reduced the credibility of the blogger. These findings are in line with those of Hwang and Jeong. [47] Their experiment showed that when consumers are skeptical toward product review posts, a simple disclosure stating that the blog was sponsored by a third-party reduced the blogger’s credibility and consumers’ attitude toward the message. However, a disclosure that stressed that the blog post was sponsored but that contents were based on the blogger’s own opinions, did not have such negative effects, and resulted in the same levels of credibility and attitudes as no disclosure. These effects can be explained by the idea that the more explicit a blogger is about the commercial connection, the more honest and credible that person is perceived to be. Therefore, consumers do not appreciate impartial, equivocal (i.e., technically true), and deceitful disclosures. [48]

27

To test whether the disclosures used in practice are consistent with the rules, we study whether disclosures explicitly mention the advertiser (i.e., the brand or product name), providing information about the relationship between the blogger and the advertiser, and whether it provides information about any compensation received. In addition, as the guidelines [49] also instruct that a disclosure should be clearly legible and noticeable, we also examine the font size.

28

Furthermore, research has demonstrated that the positioning of a disclosure influences its impact. Campbell et al. [50] showed that the effects of a disclosure depend on its timing. Participants inferred greater influence of the placement when the disclosure was presented after, rather than before, blog advertising. Moreover, a disclosure resulted in a correction of brand attitudes when presented after, but not when presented before the blog advertising. Additionally, the FTC’s .Com Disclosures document directs that a disclosure should preferably be designed in such a way that “scrolling” is not necessary to find it, emphasizing the importance of the positioning of a disclosure. [51] Therefore, we investigate where disclosures are provided (e.g., above or below blog advertising) and whether it is necessary to scroll down to see it.

29

Altogether, because the regulations provide very specific examples of how to disclose blog advertising, and empirical research implies that different forms of disclosures result in a different impact on the blog reader, it is important to assess disclosure format. Examining disclosure format allows for identifying different types of disclosures. It further allows an overview of the disclosures that are used in practice, which can be tested in further studies to disentangle which disclosures can help consumers to recognize blog advertising. Therefore, our second research question is:

RQ2: In what way is advertising in blogs disclosed?

30

Third, in an attempt to gain some understanding of the relevance of existing legal and self-regulatory provisions of social media advertising, we investigate how frequently brands are mentioned in blogs and compare this to the frequency of disclosures. Analyzing this brand-disclosure co-occurrence provides insight into the discrepancy between the provision of disclosures and the existence of blog advertising and allows us to speculate about the actual level of compliance with the regulations. In addition to the content analysis, we asked the bloggers to verify whether the inclusion of brands and products was indeed advertising. By doing so, we aim to assess how prevalent the practice of blog advertising is. Therefore, we enquire:

RQ3: How often do blogs mention brands and products, and do bloggers provide disclosures when blogs contain advertising?

31

Fourth, the social media advertising regulations between countries are similar in many ways, but there are also differences. In the US, social media advertising was implicitly covered by the FTCA but only recently addressed specifically in a guide. However, in the Netherlands further interpretation and specification of existing laws is a fairly recent development and primarily the result of self-regulation. Therefore, one might expect greater awareness among US bloggers and more compliance with the regulations than among Dutch bloggers. On the other hand, in the Netherlands bloggers are held responsible for compliance with the regulations, whereas in the US the focus is more on the advertisers. From this point of view, one might expect more strict use of disclosures among bloggers in the Netherlands. Our research question states:

RQ4: Are there any observable differences in the extent to which bloggers provide disclosures (RQ1), the disclosure format (RQ2), and brand-disclosure co-occurrence (RQ3) between the US and the Netherlands?

32

Fifth, we examine differences among the four most popular blog themes, which are food, beauty, fashion, and tech(nology). Advertising could be more natural and suitable for one blog theme (e.g., fashion blogs about clothing, and beauty blogs about make-up) than for another (e.g., food). Therefore, our last research question states:

RQ5: Are there any observable differences in the extent to which bloggers provide disclosures (RQ1), disclosure format (RQ2), and brand-disclosure co-occurrence in blogs (RQ3) between blog themes?

33

We conducted a content analysis comparing 200 blog posts from the US and the Netherlands. To determine the four biggest blog categories (categories that comprised the highest number of blogs) within the US and the Netherlands, we used www.technorati.com . The identified themes were food, fashion, beauty, and technology. Next, the five most popular blogs (with the most unique visitors per month) per theme were selected for both countries (a complete overview can be requested from the authors). For these blogs the five most recent posts were selected for the analyses. This resulted in 100 blog posts from Dutch and American blogs (N = 200). Blog posts were collected between June 2014 and October 2014, so for all blog posts the current regulations did apply.

34

Two independent coders, blind to our research questions, coded the blog posts. Both coders were trained for all variables by one of the authors. A codebook was used that was specifically developed for this study. The training procedure took approximately one month, and in this period 18% (n = 36) of the total blog posts were double coded in order to calculate the inter coder reliability. This training sample included five blog posts of each of the four blog themes for the Dutch blogs and four blog posts per theme for the American blogs. Based on this initial coding, Krippendorff's Alpha was calculated (α = 0.78) for each variable and ranged from 0.53 to 1 (see Table 1). [52] Inconsistencies found among the coders were extensively discussed in order to reach agreement. Parts of the codebook were altered and information was added because of insights that arose during the training process. Subsequently, the remaining 164 blog posts (80 Dutch blog posts and 84 American blog posts) were divided between the coders and coded by them.

35

Table 1. Overview of Intercoder Reliability

|

Variable |

Krippendorff's Alpha (α) |

|

Disclosure provided |

1 |

|

Disclosure: Mentioned brand name |

1 |

|

Disclosure: Mentioned product name |

0.62 |

|

Disclosure: Mentioned receiving of compensation |

0.63 |

|

Size of the disclosure |

0.62 |

|

Position of disclosure |

0.81 |

|

Brand names mentioned in blog post |

0.71 |

|

Promotional features mentioned in blog post |

|

|

Discount |

1 |

|

Direct link to a branded and/or selling website |

0.74 |

|

Giveaway or free sample |

Constant |

|

Slogan |

0.53 |

36

The codebook included several variables in six areas: disclosure presence, disclosure format, brands and products mentioned in blog posts, general information about the blog and blogger, general information about the blog post, and comments on the blog post. Only the relevant variables for this study are reported below.

37

We coded whether the blog post contained one or more disclosures. A disclosure is operationalized as a statement with the purpose to clarify the commercial motives of the blog advertising. All disclosures in the blog post were listed (see Table 3).

38

We coded whether the disclosure included: brand name, product name, and the receiving of compensation. In addition, we coded the size of the disclosure (i.e., if the disclosure was coded as smaller, the same size, or larger than the text in the blog post); and the placement of the disclosure, (i.e., in title, above the text, in the text, between sentences, or below the text of the blog post).

39

We also coded whether brand names were mentioned in the blog post and the number of brand names mentioned in the post. A brand was operationalized as “a distinctive commercial term used by a firm to identify and/or promote itself or one or more of its consumer products or services.” [53] All brands mentioned in the post were listed and the type of promotion (i.e., whether the blog post included the official slogan of the brand, a direct link to a branded and/or selling website, a giveaway action, or a discount for the blog readers) was coded.

40

To verify that the blog posts that mentioned brands or products were actually cases of blog advertising, we sent emails to all bloggers about these specific branded blog posts in addition to the content analysis. For the specific blog posts, we asked them whether they (1) received a payment or any form of compensation to write about these brands. And, (2) if so, what they received for this (e.g., money, a product, or a voucher), and finally (3) from whom they received this.

41

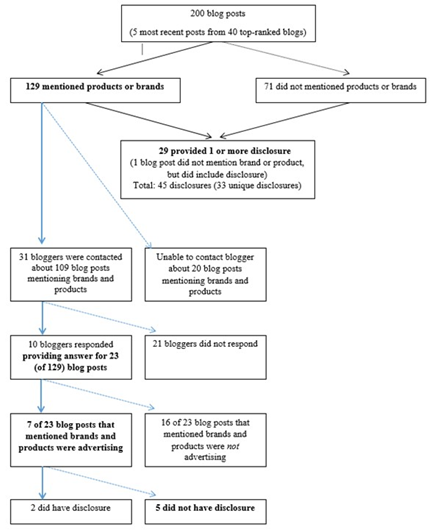

The results of the content analysis can be found in Table 2 and Figure 1. A total of 29 (15%) of the 200 coded blog posts provided one or more disclosures. Most of the blog posts (n = 20) provided one disclosure, whereas three blog posts gave two, five provided three, and one provided four disclosures. This left us with a total of 45 disclosures of commercial sponsorship.

42

Table 2. Disclosure Presence, Disclosure Format, and the Mention of Brand and Products in the Netherlands and the US

|

NL |

US |

Total |

||||

|

No |

% |

No |

% |

No |

% |

|

|

Disclosure Presence |

||||||

|

Blog posts with disclosures |

14a |

14% |

15a |

15% |

29 |

15% |

|

Branded blog posts with disclosures |

13a |

22% |

15a |

21% |

28 |

22% |

|

Disclosure Format |

N=17 |

N=28 |

N=45 |

|||

|

Mentions brand or product name |

7a |

41% |

8a |

29% |

15 |

33% |

|

Mentions receiving of compensation |

2a |

12% |

6a |

21% |

8 |

18% |

|

Size |

||||||

|

Font smaller than text blog post |

4a |

23% |

9a |

32% |

13 |

29% |

|

Font same as text blog post |

12a |

71% |

17a |

61% |

29 |

64% |

|

Font larger than text blog post |

1a |

6% |

2a |

7% |

3 |

7% |

|

Scrolling necessary to see disclosure |

11a |

65% |

20a |

71% |

31 |

69% |

|

Position of disclosure |

||||||

|

Above the blog post |

2a |

12% |

7a |

25% |

9 |

20% |

|

Between sentences of blog post |

1a |

6% |

3a |

11% |

4 |

9% |

|

Below the blog post |

9a |

53% |

14a |

50% |

23 |

51% |

|

In text of blog post |

3a |

18% |

3a |

11% |

6 |

13% |

|

First word or sentence |

2a |

12% |

0a |

0% |

2 |

4% |

|

In title |

0a |

0% |

1a |

4% |

1 |

2% |

|

Brand and products |

||||||

|

Blog posts that mention brands |

58x |

58% |

71y |

71% |

129 |

65% |

|

Verified as advertising |

6 |

10% |

1 |

1% |

7 |

5% |

|

Type of promotion |

||||||

|

Discount |

0x |

0% |

3y |

3% |

3 |

2% |

|

Direct link to website |

25a |

25% |

43b |

43% |

68 |

34% |

|

Giveaway or free sample |

1a |

1% |

2a |

2% |

3 |

2% |

|

Slogan |

0a |

0% |

0a |

0% |

0 |

0% |

Note. a,b Numbers with a different superscript in the same row differ significantly between countries at p < .05 NL = The Netherlands.

x, y Numbers with a different superscript in the same row differ significantly between countries at p < .10.

43

Because some blog posts provided more than one disclosure, a total of 45 individual disclosures were analyzed. Format varied a lot, as can be seen from the 33 unique disclosures that were found (see Table 3). Of all disclosures, 15 mentioned the brand or product name (which is 33% of all disclosures), and only eight mentioned compensation received from the advertiser. Furthermore, most of the disclosures (n = 29, which is 64% of all disclosures) had the same font size as the blog post text. Only three had a larger font, making it stand out from the blog post, whereas 13 had a smaller font size, making it harder to notice. Despite FTC regulations stating that scrolling down should not be necessary to see the disclosure, in 31 (69% of all disclosures) of the cases it was necessary to scroll down. In line with this finding, 23 of the disclosures were located below the blog post (which is more than half, 51%, of all disclosures). Nine disclosures (20%) were positioned above the text, six (13%) within the text, and two were in the first sentence (4%). One disclosure was part of the title.

44

In total, 65% of the blog posts mentioned brands. On average, blog posts mentioned 1.49 brands (SD = 1.77). Most blog posts (n = 69) cited one brand, whereas 13 of the blog posts mentioned the maximum number of six brands. When selecting the 129 branded blog posts, the mean number of brands mentioned was 2.30 (SD = 1.73). This means that many blog posts contain brands or product names, and when they do, they typically mention more than two.

45

Three of the blogs included a discount for the brand or product, three advertised a giveaway or free sample, but none cited a slogan. Of all blog posts, 34% provided a direct link to the website of the brand or a website selling the brand. Most of these blog posts (n = 48) provided one hyperlink, and two provided a maximum of six links. In addition, 31 of the blog posts contained videos, and in 58% (n = 18) of them, one or more brands were mentioned.

46

Of the 129 branded blog posts, 22% (n = 28) included a disclosure. One Dutch blog post provided a disclosure but did not mention any brands in the blog (making the total of blog posts with disclosure 29). The disclosure itself said: “This trip was offered to me by Visit Valencia.com and Tix; see my disclaimer here” (Table 3, Case 2, The Netherlands). In this case the blog post was advertising a trip to the Spanish city and a travel website. This shows that disclosures are necessary, even when the commercial relationship does not revolve around a specific brand.

47

The low level of brand-disclosure co-occurrence of merely 22% indicates a low level of compliance with the social media advertising regulations. Before drawing any conclusions regarding bloggers’ compliance with the regulations, we had to verify whether these branded blogs were actually advertising. The 129 branded blog posts stemmed from 38 unique blogs (Min = 1 branded blog post stemming from a blog, Max = 5). We were able to send 31 blog(gers) an email about 109 of the branded blog posts to verify the purpose of the brand or product mentions. These emails included 15 direct emails to the blogger, 16 indirect emails via the website contact form, ‘info’ email address, or the bloggers’ management. The remaining seven blogs, responsible for 20 of the branded blog posts, did not provide any contact information (for an overview see Figure 1).

48

We received an answer to our emails from 10 bloggers (32% of the sent emails). These 10 emails were about 27 different blog posts. Two of the responses did not address the questions about the blog posts, so for four blog posts the background remained unclear. This means we got an answer to whether 23 (of a total of 129) branded blog posts were actually a case of blog advertising.

49

Table 3. Disclosures Provided in Coded Blog Posts (in Random Order)

|

The Netherlands |

US |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. * Disclosures from Dutch blogs that were translated into English.

50

For 16 blog posts, the bloggers said they did not receive any compensation to write about the brands mentioned in them. Seven of the 23 blog posts mentioning brands were a result of a commercial relationship: one blogger was paid to write a blog post about the brand, one was a PR deal, one received a trip, one blogger made a deal with a restaurant, and three received the product to review it on their blog. Interestingly, five of these seven blog posts containing advertising did not include a disclosure of this relationship to the brand. Although six of the ten bloggers we emailed, explicitly told us to always disclose any commercial relationship (without us asking them), our small sample of blog advertising (n = 7) shows bloggers certainly do not always comply with the social media advertising regulations.

51

To answer RQ4, we compared the two countries by conducting chi-square analyses for the dichotomous variables, and ANOVAs for the continuous variables. We found little significant differences between the two countries. For brevity and clarity, we only report the significant differences. Results showed that there is a marginal significant difference between the countries with respect to the number of blog posts that mentioned brands, χ2 (1) = 3.69, p = .055. The American blog posts seem to include brands more often (71%) than Dutch blog posts (58%).

52

With regard to the type of promotion, the Dutch blog posts provided no discounts for a brand or product, whereas a few (3%) American blog posts did. This difference was marginally significant, χ2 (1) = 3.05, p = .081. Moreover, the American blog posts provided direct links to a website selling the brand or the website of the brand itself (43%) more often than the Dutch blog posts (25%), χ2 (1) = 7.21, p = .007. In addition, the American blog posts (M = 0.78, SD = 1.28) provided significantly more links than the Dutch blog posts (M = 0.33, SD = 0.67), F(1, 198) = 9.67, p = .002, η2 = .05.

53

Figure 1. Overview of content analysis and results of contact with bloggers

54

To answer RQ5, we compared the four blog themes by conducting chi-square analyses for the dichotomous variables, and ANOVAs for the continuous variables. Again, we only report the significant differences.

55

There was a marginal significant difference in the use of disclosures, χ2 (3) = 7.54, p = .056, and a significant difference in the number of disclosures provided per blog post, F(3, 196) = 4.93, p = .003, η2 = .07, among blog themes. The figures clearly show that most disclosures (26%) are provided in beauty blogs. Bonferroni post hoc comparisons showed that blog posts on beauty blogs (M = 0.52, SD = 1.03) contained significantly more disclosures, compared to food (M = 0.12, SD = 0.48), fashion (M = 0.14, SD = 0.40), and tech (M = 0.12, SD = 0.33) blogs.

56

Comparing the 45 disclosures provided in the blog posts revealed significant differences in the blog themes with regard to mentioning brands or products in the disclosure, χ2 (3) = 13.16, p = .004: Disclosures used in fashion blogs most often mentioned brand or product names.

57

Furthermore, there were significant differences in the mentioning of brands, χ2 (3) = 29.59, p < .001, and the number of brands mentioned, F(3, 196) = 9.10, p < .001, η2 = .12 among the blog themes. Mostly fashion (78%) and beauty (80%) blogs mentioned brands (tech 66%, food 34%). Post hoc analyses using the Bonferroni adjustment showed that there were significantly more brands mentioned in fashion blogs (M = 2.28, SD = 2.08) compared to food (M = 0.60, SD = 1.21) and tech (M = 1.30, SD = 1.54) blogs, and significantly more brands mentioned in beauty blogs (M = 1.76, SD = 1.73) compared to food blogs. In other words, fashion and beauty blogs mentioned the most brands and product names.

58

When selecting only the 129 branded blogs, the number of disclosures significantly differed between blog themes, F(3, 125) = 3.34, p = .022, η2 = .07. Bonferroni post hoc analyses showed that beauty blogs (M = 0.65, SD = 1.12) provided significantly more disclosures than fashion blogs (M = 0.18, SD = 0.45), and marginally significantly more than tech blogs (M = 0.18, SD = 0.39), but not compared to food blogs (M = 0.29, SD = 0.77). All other comparisons were not significant. This indicates that beauty blogs most often mention brands and also provide the most disclosures of advertising.

59

This study presented the regulations in the EU - specifically The Netherlands - and the US on blog advertising, and systematically assessed actual practice of disclosure by studying a sample of popular blog posts. The FTCA and related guides in the US, and self-regulative provisions in Europe urge advertisers and endorsers, such as bloggers, to disclose any commercial relation. These disclosures should be clear and conspicuous [54] because advertising to consumers should be recognizable as such. However, our legal and content analyses show a significant discrepancy between legal rules and actual practice. Accordingly, our content analysis of 200 blog posts from the 40 most popular blogs across four different blog themes and two countries, provided us with five insights about what bloggers actually say and do, which are particularly relevant to the current regulations.

60

First, our study shows that 15% of all blog posts provided one or more blog advertising disclosures. This demonstrates that at least some blog posts were in compliance with the legal and self-regulatory provisions and provided blog advertising disclosures.

61

Second, a comparison of the 45 blog advertising disclosures in the sample shows that there is great diversity in the way disclosures are presented. This demonstrates that there is certainly not one uniform disclosure format. Although the codes and regulations in both the Netherlands and the US require a blogger to specifically mention any connection with an advertiser, only one-third of the disclosures mentioned the brand or product name (as required by the rules). Many of the disclosures only stated “sponsored,” “affiliated link,” “PR sample,” or “advertorial.” Moreover, very few disclosures stated that the blogger had received compensation. An important note to this issue is that we cannot determine which of the blogs actually did receive compensation and did not mention this. This could indicate that bloggers do not often receive compensation, or that when bloggers are paid, they rarely mention it.

62

Concerning the size of the disclosure, we found that most (64%) are presented in the same font as the text of the blog post, but many also use a smaller font. Most of the time, disclosures are placed below the blog post, often requiring scrolling to see the disclosure. This is not in accordance with the requirement that a disclosure must be presented in a clear and accessible manner and should ideally be visible without scrolling. However, research on the positioning of disclosures [55] showed that disclosures at the end of a blog can be effective. Thus far, we can conclude that the existing rules could be improved by being better informed by empirical evidence in actual user behavior.

63

According to the FTC .Com Disclosure document, “The ultimate test is whether the information intended to be disclosed is actually conveyed to consumers”. [56] Overall, our findings indicate that, although disclosures are sometimes provided, bloggers usually do not make an effort to create a prominent disclosure, making it difficult for the consumer to notice it, and calling in question the efficacy of those disclosures that are provided. Additionally, many disclosures do not provide sufficient information to understand the connection between the blogger and advertiser.

64

Third, our study shows that blogs do often mention brands and product names. Of the 200 blog posts coded, two-thirds mentioned one or more brands and product names. An important limitation of a content analysis, however, is that we cannot be sure whether the brands and product names are mentioned because of a commercial connection with this brand. In an attempt to verify whether the blogs mentioning brands were actually advertising, we contacted the bloggers behind these blogs. Although very few responded, this did show that many blog posts mentioning brands or products were not based on a commercial relationship (70%, i.e., 16 of 23), but it could also mean that the bloggers in question were not willing to disclose that relationship to the researchers. If anything, these findings point to some of the difficulties with monitoring for compliance.

65

Fourth, our study reveals some interesting differences between the Netherlands and the US. The American blog posts appear to include brands more often than Dutch blog posts, and they include more promotional features, such as discounts and links to a brand’s website, or websites selling specific brands. Based on this, American blogs may be more commercial in nature than their Dutch counterparts. However, we found no differences in the use of blog advertising disclosures.

66

Fifth, our results demonstrated some distinctions among the four most popular blog themes (i.e., food, beauty, fashion, and tech). Blogs about fashion and beauty contained the most brand and product names. Probably these blogs often include posts about makeup and clothing from specific brands, making it more likely to include brands than food and technology blogs. Interestingly, the use of disclosures is also highest within these themes. Fashion blogs in particular mentioned brand or product names, clearly informing readers about a commercial connection. These are promising findings, indicating that blog themes in which the mentioning of brands is most natural and most often used shows greater compliance with the regulations requiring disclosures. Future research may specify how this develops for other blog themes.

67

An important limitation of our study is that we analyzed blog posts from 2014. Although the codes and regulations already urged the disclosure of sponsored content in 2014, since then, the codes and guides have been updated (e.g., the US Endorsement Guides were updated in 2016 and the Dutch Advertising Code was updated in 2017). In addition, as the FTC noticed that many influencers did not clearly and conspicuously disclose their relationships to brands, they sent out more than 90 letters warning and reminding influencers and marketers of their obligation to disclose commercial relationships. [57] Future research is needed to investigate whether these new developments have affected whether and how bloggers disclose blog advertising, and to ascertain how effective these new measures and efforts have been.

68

Our findings provide some important implications for the theoretical development of the effects of sponsorship disclosures and further research. Table 3 shows an overview of the disclosures used in real life. The Persuasion Knowledge Model is often used as a theory that can explain why disclosures may influence consumer’s responses to sponsored content. [58] The archetypes of disclosures derived from this study should be tested to examine whether these disclosures are clear and understandable (a requirement in the regulations for both the Netherlands and US) and thus whether they can actually increase the use of persuasion knowledge. This is not something we can derive from this content analysis. The existing variety and lack of standardization may lead to confusion among users. More research could provide vital information about the extent to which consumers understand the disclosures, the best format to effectively inform consumers about the commercial nature of a blog post, and whether there is a need for standardization.

69

Although the advertisers are responsible for compliance with the regulations, they are also responsible for training their endorsers to use adequate disclosures. Other possible areas for research include the level of awareness of the rules among bloggers, the extent to which the existing rules match with social norms and ethical perceptions among bloggers, the extent to which advertisers develop monitoring and training schemes, and the way in which they ensure (or fail to ensure) compliance with the rules. Furthermore, further research in the legal area could relate to the broader question about the extent to which professional parties can be held legally accountable or responsible for the actions of amateur users.

70

Finally, these findings also have important implications for law and policy. Transparency and disclosures are a central element in consumer protection and in the context of social media advertising. The current findings suggest that for the time being, compliance with the rules for blog advertising may be rather low. In case bloggers do provide disclosures, the format varies, which can possibly lead to further confusion among users, and may be an argument in favor of stipulating clearer guidance on or even standardization of the disclosure format. This is in light of the fact that bloggers will typically be legal laymen, and in the absence of clear guidance, will find it difficult to judge when a disclosure is in compliance with the regulations.

71

This study has also demonstrated how difficult it is for the monitoring authorities to actually ascertain whether a conflict with the existing regulations is present. Though blogs do seem to mention brands frequently, it is difficult to conclude from this alone the existence of a relevant relationship or connection to an advertiser and rule out other explanations, such as social habits and the way the mentioning of brands is integrated in the way users communicate. In addition, given the large variety of disclosures provided in blogs, also the disclosures themselves are difficult to recognize and monitor. Finally, even if empirical evidence finds instances of non-compliance, clear standards are still missing on how solid this evidence needs to be to be externally valid and justify intervention. Therefore, while this study suggests that the rules are relevant, it also suggests that monitoring and compliance would need to focus on the advertisers (as the FTC has already indicated). Additional arguments in favor of concentrating on advertisers is that here the incentives to comply are probably the lowest (as disclosure can have a potentially adverse effect on the advertising outcomes), as well as the potential invasiveness and privacy-intrusiveness of monitoring compliance on the side of users.

The authors would like to thank Anne-Jel Hoelen from the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) for her constructive feedback and useful suggestions, and Melanie de Looper and Youssef Fouad for their assistance during this project.

* By Dr Sophie C. Boerman, assistant professor of Persuasive Communication, Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), University of Amsterdam;

Dr Guda van Noort, associate professor of Persuasive Communication, Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), University of Amsterdam;

Prof. Dr Natali Helberger, professor of Information Law, Institute for Information Law (IViR), University of Amsterdam;

Prof. Chris J. Hoofnagle, adjunct professor of law and of information, University of California, Berkeley.

[1] Interactive Advertising Bureau [IAB], Digital advertising revenues hit $19.6 billion in Q1 2017, climbing 23% year-over-year, according to IAB (2017), available at https://www.iab.com/news/ad-revenues-hit-19-6b/ .

[2] AJ Agrawal, Why influencer marketing will explode in 2017 (2016), available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/ajagrawal/ .

[3] Marijke de Veirman, Veroline Cauberghe, and Liselot Hudders. Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising 36, 798-828 (2017).

[4] Long-Chuan Lu, Wen-Pin Chang, and Hsiu-Hua Chang. Consumer attitudes toward blogger’s sponsored recommendations and purchase intention: The effect of sponsorship type, product type, and brand awareness. Comput Hum Behav. 34, 258-266 (2014).; June Zhu and Bernard Tan. Effectiveness of blog advertising: Impact of communicator expertise, advertising intent, and product involvement. (2007) ICIS 2007 Proceedings, Montreal, available at http://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/ .

[5] Sophie C. Boerman, Eva A. Van Reijmersdal and Peter C. Neijens. Sponsorship disclosure: Effects of duration on persuasion knowledge and brand responses. Journal of Communication. 62, 1047-1064 (2012).

[6] Federal Trade Commission [FTC] The FTC’s endorsement guides (2015), available at https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/ .

[7] Word of Mouth Marketing Association [WOMMA]. WOMMA social media disclosure guidelines (2017), available at http://womma.org/wp-content/uploads/ ; The Dutch Advertising Code with information about the working procedures of the advertising code committee and the board of appeal (2017), available at https://www.reclamecode.nl/bijlagen/SRCNRCEngelsmei2017.pdf ; Social Code, Richtlijnen voor reclame in online video (2017), available at https://www.cvdm.nl/wp-content/ .

[8] European Commission, COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL AND THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE. A New Deal for Consumers, COM/2018/0183 final, Brussels, 11.4.2018.

[9] Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL amending Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5 April 1993, Directive 98/6/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Directive 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards better enforcement and modernisation of EU consumer protection rules, Brussels, 11.4.2018 COM(2018) 185 final, (p. 18, though primarily for the situation of search engines).

[10] See e.g. International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), Advertising and Marketing Communication Practice, Consolidated ICC Code, Paris, 2011.

[11] Caleb T. Carr and Rebecca A. Hayes. The effect of disclosure of third-party influence on an opinion leader's credibility and electronic word of mouth in two-step flow. Journal of Interactive Advertising 14, 38-50 (2014).; Yoori Hwang and Se-Hoon Jeong. “This is a sponsored blog post, but all opinions are my own”: The effects of sponsorship disclosure on responses to sponsored blog posts. Comput Hum Behav 62, 528-535 (2016).; Eva A. Van Reijmersdal et al. Effects of disclosing sponsored content in blogs: How the use of resistance strategies mediates effects on persuasion. Am Behav Sci. 60, 1458-1474 (2016); Jonas Colliander and Susanna Erlandsson. The blog and the bountiful: Exploring the effects of disguised product placement on blogs that are revealed by a third party. Journal of Marketing Communications 21, 110-124 (2015).; Veronica Liljander, Johanna Gummerus, and Magnus Söderlund. Young consumers’ responses to suspected covert and overt blog marketing. Internet Research 25, 610-632 (2015).; Chris J. Hoofnagle, and Eduard Meleshinsky. Native advertising and endorsement: Schema, source-based misleadingness, and omission of material facts. Technology Science (2015).

[12] Carr and Hayes supra note 7; Hwang and Jeong supra note 7; Bartosz Wojdynski and Nathanial Evans. Going native: Effects of disclosure position and language on the recognition and evaluation of online native advertising. Journal of Advertising 45, 157-168 (2016).; Nathaniel Evans, Joe Phua, Jay Lim and Hyoyeun Jun. Disclosing Instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral intent. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 1-12 (2017).

[13] For video content on social media the self-regulatory initiative by a number of “YouTubers for YouTubers” is worth mentioning, in which YouTubers under the auspice of the Dutch Media Regulator, i.e. the authority for the regulation of advertising in video content, commit to observing transparency in reporting about commercial influences (but also where YouTubers bought products), and give concrete examples how this should be done, Social Media Code: YouTube, 2017, available at https://www.cvdm.nl/wp-content/ and https://www.desocialcode.nl/ .

[14] Dirk Willem Frederik Verkade. Oneerlijke handelspraktijken jegens consumenten. Vol 49. Kluwer (2009).

[15] Art. 2 (b) Unfair Commercial Practice Directive. Note that falsely claiming or creating the impression that a trader is not acting for purposes if his trade or represents himself as a consumer constitutes an unfair commercial practice, according to No. 22 of the Annex I of the Unfair Commercial Practice Directive.

[16] The Dutch Advertising Code supra note 6.

[17] Not at least because Art. 193 g of the Dutch Civil Code, according to which claiming to be committed to self-regulation, while not acting in accordance with that regulation constitutes a commercial practice that is always unfair, Art. 193g (1) of the Dutch Civil Code.

[18] The Dutch Advertising Code Authority can only publish findings of non-compliance and, if necessary, bring them to the attention of the Dutch Authority for Consumers and Markets, who then can decide to initiate an enforcement action.

[19] DDMA. Vloggen: Hoe heurt het eigenlijk? (2017) available at https://ddma.nl/actueel/ .

[20] The Dutch Advertising Code supra note 6.

[21] The Dutch Advertising Code supra note 6.

[22] RCC 17 November 2015, 2014/00917 (Daniel Wellington & Influencers).

[23] RCC 2 October 2017, 2017/00518 (Rivella & Doutzen Kroes); RCC 26 October 2017, 2017/00650 (Corendon & Influencer).

[24] ACM. ACM calls for increased transparency in online reviews (2017), available at https://www.acm.nl/en/publications/publication/ ; ACM. Richtlijnen voor ondernemers voor gebruik online reviews. (2017), available at https://www.acm.nl/nl/publicaties/publicatie/ .

[25] Chris J. Hoofnagle. Federal trade commission privacy law and policy. Cambridge University Press (2016).

[26] FTC v. Muenzen, 1 F.T.C. 30 (1917).

[27] Advisory Opinion 191, Advertisements which appear in news format, Dk. No. 683 7080, 73 F.T.C. 1307. February 16, 1968.

[28] In the Matter of Lord & Taylor, LLC, No. 152 3181 (2016).

[29] In the Matter of CSGOLotto, Inc. et al., No. 162 3184 (2017).

[30] The FTC’s endorsement guides supra note 5.

[31] The FTC’s endorsement guides supra note 5; US Government Publishing Office. Electronic code of federal regulations (2017), available at https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/ ; FTC. Native advertising: A guide for businesses (2015), available at https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/ ; Mediakix. FTC endorsement guidelines for 2016 [infographic], (2016), available at http://mediakix.com/2016/09/ .

[32] The FTC’s endorsement guides supra note 5.

[33] The FTC cites the example of a film star who advertises a product. Here the audience can reasonably expect that the film star has been paid, making it unnecessary to disclose that connection. See also the definition in the guidelines of the WOMMA (2017, p. 1): “A “material connection” is any relationship between a speaker and a company or brand that could affect the credibility audiences give to that speaker’s statements or influence how the audience feels about that company or brand; (for example, because of perceived bias); this can include any benefits or incentives such as monetary payment, free product, exclusive or early access, value-in-kind, discounts, gifts (including travel), sweepstakes entries, or an employer/employee or other business relationship.”

[34] The FTC’s endorsement guides supra note 5.

[35] The FTC’s endorsement guides supra note 5.

[36] The FTC’s endorsement guides supra note 5; Federal Trade Commission [FTC]. .Com disclosures. how to make effective disclosure in digital advertising. (2013), available at http://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/ .

[37] The FTC’s endorsement guides: What people are asking. (2015), available at https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/ .

[38] Final consent order in the matter of ADT LLC, DOCKET NO. C-4460 (2012), available at http://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ .

[39] WOMMA supra note 6.

[40] Carr and Hayes supra note 7; Hwang and Jeong supra note 7; Colliander and Erlandsson supra note 7.

[41] Liljander, Gummerus, and Söderlund supra note 7.

[42] Margaret C. Campbell, Gina S. Mohr, and Verlegh Peeter W.J. Can disclosures lead consumers to resist covert persuasion? The important roles of disclosure timing and type of response. Journal of Consumer Psychology 23, 483-495 (2013).

[43] Peeter W.J. Verlegh, Gangseog Ryu, Mirjam A. Tuk, and Lawrence Feick. Receiver responses to rewarded referrals: The motive inferences framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 41, 669-682 (2013).

[44] Van Reijmersdal et al. supra note 7.

[45] Robert V. Kozinets, Kristine de Valck, Andrea C. Wojnicki, and Sarah J. S. Wilner. Networked narratives: Understanding word-of-mouth marketing in online communities. J Market 74, 71-89 (2010).

[46] Carr and Hayes supra note 7.

[47] Hwang and Jeong supra note 7.

[48] Carr and Hayes supra note 7.

[49] The FTC’s endorsement guides supra note 5; The Dutch Advertising Code supra note 6.

[50] Campbell, Mohr, and Verlegh supra note 37.

[51] FTC .Com disclosures supra note 31.

[52] Andrew F. Hayes and Klaus Krippendorff. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication methods and measures 1, 77-89 (2007).

[53] Monroe Friedman. The changing language of a consumer society: Brand name usage in popular American novels in the postwar era. Journal of Consumer Research 11, 927-938 (1985).

[54] WOMMA supra note 6; The Dutch Advertising Code supra note 6; FTC .Com disclosures supra note 31.

[55] Campbell, Mohr, and Verlegh supra note 37.

[56] FTC .Com disclosures supra note 31.

[57] FTC Staff Reminds Influencers and Brands to Clearly Disclose Relationship. (2017), available at https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/ .

[58] Boerman supra note 4; Hwang and Jeong supra note 7.