Untitled Document

urn:nbn:de:0009-29-57378

1. Introduction*

1

Lately, teaching has had to adapt to fundamental and urgent shifts. After more than two years into a global pandemic and several COVID-19 variants, life is progressively returning to normal. The majority of governments have lifted several, if not all, restrictions. This trend is valid for academic life as well. With Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) shut down for a large part of 2020 and 2021 and engaged with dual delivery and gradual return to in-person teaching in 2022, the academic year 2022/2023 is seeing a general resumption of on-campus activities. However, it is unlikely that things will return to exactly as they were before the COVID-19 pandemic. Firstly, as public health experts warn, COVID-19 is still “a global health threat”. [1] Hence, we might need to remain flexible and be prepared to face future emergencies. [2] Secondly, education has seen a paradigmatic digital shift over the past three years. Several investments have been made, new service providers have entered the market and offered additional services, staff have been trained on these services, further teaching methodologies have been developed, and several have proven pedagogically helpful or simply more efficient in addressing some issues (e.g., the lack of teaching spaces). Hence, some tools introduced during the pandemic are likely to remain.

2

This might be the case with e-proctoring systems. These are technologies designed to monitor student behaviour during online exams. Their function is to replicate in-person invigilation and guarantee the integrity of exams. [3] However, the extensive intrusion into the private sphere of students and numerous publicised cases of discriminatory outcomes [4] have raised several questions about these tools.

3

Used for many years now in some parts of the world, online proctoring software entered European HEIs during the first COVID-19-related lockdowns. Faced with urgent rules, HEIs were forced to reflect on how to guarantee the integrity of online exams, opting in some cases for e-proctoring solutions. This brought the conversation on the credibility, necessity, and reliability of e-proctored assessment methods to the forefront of academic discourse.

4

The growing use of e-proctoring tools in European HEIs during the pandemic is confirmed in an explorative study the authors conducted between April and July of 2021. [5] The research targeted 38 HEIs in the United Kingdom, Italy, and the Netherlands, collecting 194 responses to a 32-question survey. It resulted that 13.10% of educators have been using e-proctoring systems during the pandemic, and 8.70% were offered the possibility to opt-out and choose a non-e-proctored alternative. [6] These results cannot be generalised, but they signal the emergence of e-proctoring usage among traditionally non-distant education providers. At the same time, they show that e-proctoring was not the only means to guarantee the integrity and validity of exams, as a large part of the respondents organised online exams without remote invigilation.

5

By now, most universities are back to on-site exams. However, the possibility of yet another upsurge of the coronavirus has led a few HEIs to ensure that formal rules for reinstalling online proctoring processes are in place for when the circumstances might make it necessary. These rules, incorporated, for example, as Examination Board rules and responsibilities, describe the framework for organising distance (written) exams with online fraud prevention measures. While almost lifted everywhere, pandemic-related restrictions have left long-standing traces in the functioning of HEIs and the performance of educational activities. This legacy makes the critical evaluation of e-proctoring systems a necessary exercise for the determination of academic education imaginaries in a hybrid future.

6

The paper aims to map the legal landscape of e-proctoring in the EU. To this end, this contribution provides a brief overview of the technical aspects of e-proctoring systems (Section 2) and existing literature (Section 3) to map the state of the art of the debate. Section 4 critically discusses the case law consolidated over the past two years around e-proctoring systems, identifying points of convergence and divergence between the decisions. Section 5 reflects on the role of collective actions to enforce data protection rights and on the limited role it played in the e-proctoring controversies. After the submission of this contribution for review, a preliminary decision in the field of anti-discrimination law was issued for the first time in the Netherlands. Section 6 includes this relevant update and focuses on the legal means beyond data protection law for countering the discriminatory effects caused by the adoption of some e-proctoring tools. Section 7 sums up the results of the research.

2. E-proctoring systems: a brief technical overview

7

E-proctoring systems include a set of methods, software, and devices to monitor students at distance during an online test or exam. Online proctoring systems were already developed and used before the pandemic. [7] This was not only the case for massive open online courses (“MOOCs”) and online HEIs but, in some circumstances, also traditionally non-distant learning institutions were relying on them (e.g., to organise computer-based tests at universities for a large cohort of examinees or to introduce more flexibility for some categories of students, such as athletes). [8] However, during the pandemic, their use has become much more widespread as, in some cases, it was considered the only available solution to perform exams and ensure their integrity.

8

Nowadays, various third-party commercial options are specifically designed to manage online exams and remote student invigilation. In principle, such tools enable HEIs and staff members to verify the student's identity at the beginning of the exam, monitor their activity, set up technical restrictions on their computer (e.g., block browsing during the exam or disable copy-paste shortcuts), remotely control and manage the exam and generate a report out of the monitoring activity. [9]

9

With reference to the invigilation modalities, Hussein et al classify e-proctoring tools into three main categories: live proctoring, recorded proctoring, and automated proctoring. [10]

10

The first solution, live proctoring, essentially replicates the physical surveillance but via webcams and microphones. Here, a physical proctor remotely verifies the student’s identity at the beginning of the exam and monitors their video and audio during the whole duration of the session. In some cases, the invigilator can require a video scan of the workspace to verify that the student does not have any forbidden material at hand.

11

The second category, recorded monitoring, involves capturing and storing students' video, audio, computer desktop, and activity log for a subsequent human check.

12

Finally, automated proctoring relies on artificial intelligence systems to verify, for example, students’ identities via a biometric recognition system and/or to automatically detect suspicious behaviours. In this latter case, the algorithm processes students’ data (e.g., eye or facial movements, voice, keystroke loggings) and environmental data (such as background noise and the presence of other people in the room) to spot signs of cheating. [11] In case of anomalies, the system flags the issue for human review—usually the professor or the trained proctor—or can automatically terminate the assessment.

13

Many e-proctoring services usually offer a combination of the features mentioned above. As this brief overview suggests, there are various levels of intrusiveness in the students' personal sphere depending on the proctoring modalities or the adopted settings. In any case, they all process personal data (relating to the examinees, the examiners, and potentially third parties entering the room), thus triggering the application of data protection law. In the next Section, we will outline the risks and legal issues raised by e-proctoring as emerging from the literature.

3. Legal issues of e-proctoring

14

The increased use of e-proctoring systems has raised several concerns, including from a legal perspective. In the literature, many authors have stressed the potential clash between the use of such tools and fundamental rights and freedoms, particularly regarding the right to privacy, data protection, and non-discrimination.

15

For instance, it has been emphasised that the use of e-proctoring tools is likely to create or foster inequalities, e.g., for disabled people (who can be penalised by the anti-fraud system because they need to use screen readers or dictation software), [12] people with caring responsibilities (whose exam can be disrupted if the person they care for requires their immediate attention), or low income students who might not be able to afford suitable technical equipment, a reliable internet connection, or a room of their own. [13]

16

Moreover, the risk for ethnic minority groups is particularly high when using facial recognition technologies. Several studies have shown that such software is often trained on biased datasets and are systematically better at recognising white people, and particularly white men. [14] Hence, negative consequences for certain groups may occur due to the error rates of such tools or their deployment in a particular context.

17

Concerning privacy, the tracking of students’ activity increases the risks of surveillance. [15] In this respect, scholars have warned against the chilling effect that pervasive monitoring can have on “students’ intellectual freedom” [16] and their educational privacy. [17]

18

Scholars have also expressed serious concerns about e-proctoring from a data protection perspective. The automated decision-making process performed by such software can impact examinees in a significant way (i.e., the suspected behaviour can be reported, or the exam can be automatically terminated), and it remains unclear to what extent the ex-post human review is an appropriate guarantee in practice. [18]

19

Moreover, unlike its analogic counterpart, e-proctoring technologies inevitably generate new data and favour their collection and storage. The retention of such amounts of data increases, as a consequence, the risks of the re-purposing and sharing of data without the data subject’s awareness. [19] Such risks might range from situations where the HEI has an obligation to disclose such information to the commercial uses performed by the e-proctoring tools or to data breaches. [20]

20

Data security is, indeed, another critical point highlighted in the literature. Security concerns are even more worrisome considering the intimate nature of the data processed via e-proctoring (i.e., exam results, but potentially also biometric data). [21]

21

Furthermore, the potential threat to fundamental rights caused by e-proctoring is directly recognised in the AI Act proposal, [22] where AI systems intended to assess students or determine their access to educational programs are classified as high-risk (hence, subject to stringent rules for their authorisation). [23]

22

Lastly, the choices that dictate the use of e-proctoring systems contribute to shaping our modern educational infrastructures, with a potential effect on education itself. This means that the existing risks for privacy, data protection as well as the discriminatory effects of these systems all become particularly salient beyond the individual, on a broader societal level.

23

Some of the legal issues just outlined in this paragraph have been challenged before European courts and supervisory authorities over the past few years, mainly from a data protection perspective. Very recently, the discriminatory effect posed by these systems has been challenged in the Netherlands.

24

In the following Sections, the decisions concerning e-proctoring will be critically analysed to understand the state of play of this evaluation of practice within the EU legal framework. Section 4 will focus on data protection: the paper will assess the main arguments used in the decision to see to what extent the GDPR can protect against the risks raised by monitored online exams. Section 6 will discuss the anti-discrimination case and the possible remedies available under the equality framework.

4. E-proctoring cases and data protection: a critical analysis

25

The data protection implications of e-proctoring tools have been assessed in a few European legal systems so far and with different outcomes. We counted one pre-pandemic decision [24] and seven decisions from 2020 onwards. [25] In terms of data protection authorities (“DPA”) guidance, the French Commission Nationale Informatique & Libertés (“CNIL”) has issued a note with recommendations on surveillance and online exams in 2020. [26]

26

The e-proctoring systems examined in the court decisions varied, ranging from recorded to automated proctoring. [27] Such systems were partly customisable, and the HEIs adopted different features and retention policies. None of these cases reported the use of a facial recognition system to authenticate the examinees, nor the adoption of a fully automated decision-making process (i.e., there is no automated termination of the exam, but the recorded video/audio and the score for the deviant behaviour are reviewed ex post and the final decision is made by the examiner or the examination board). [28]

27

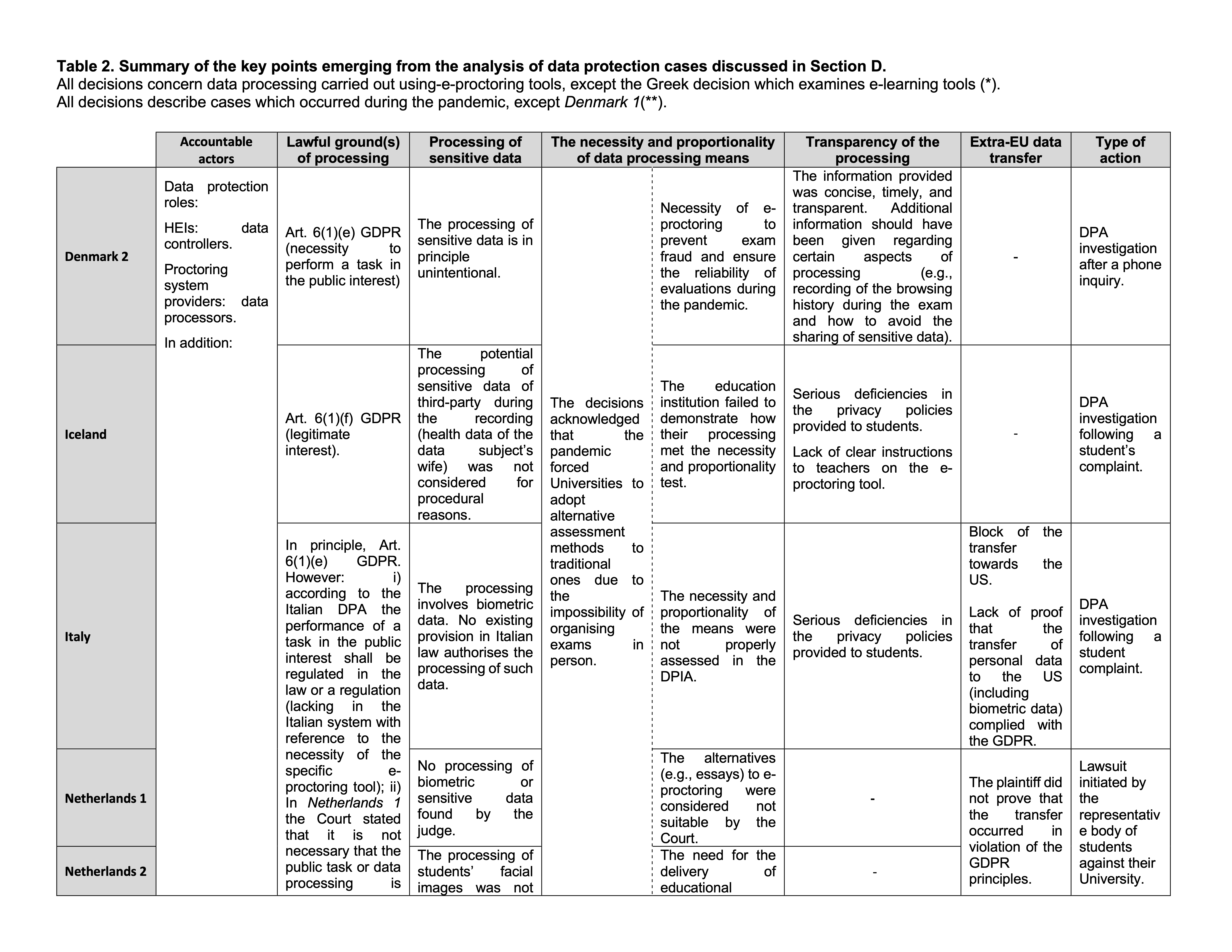

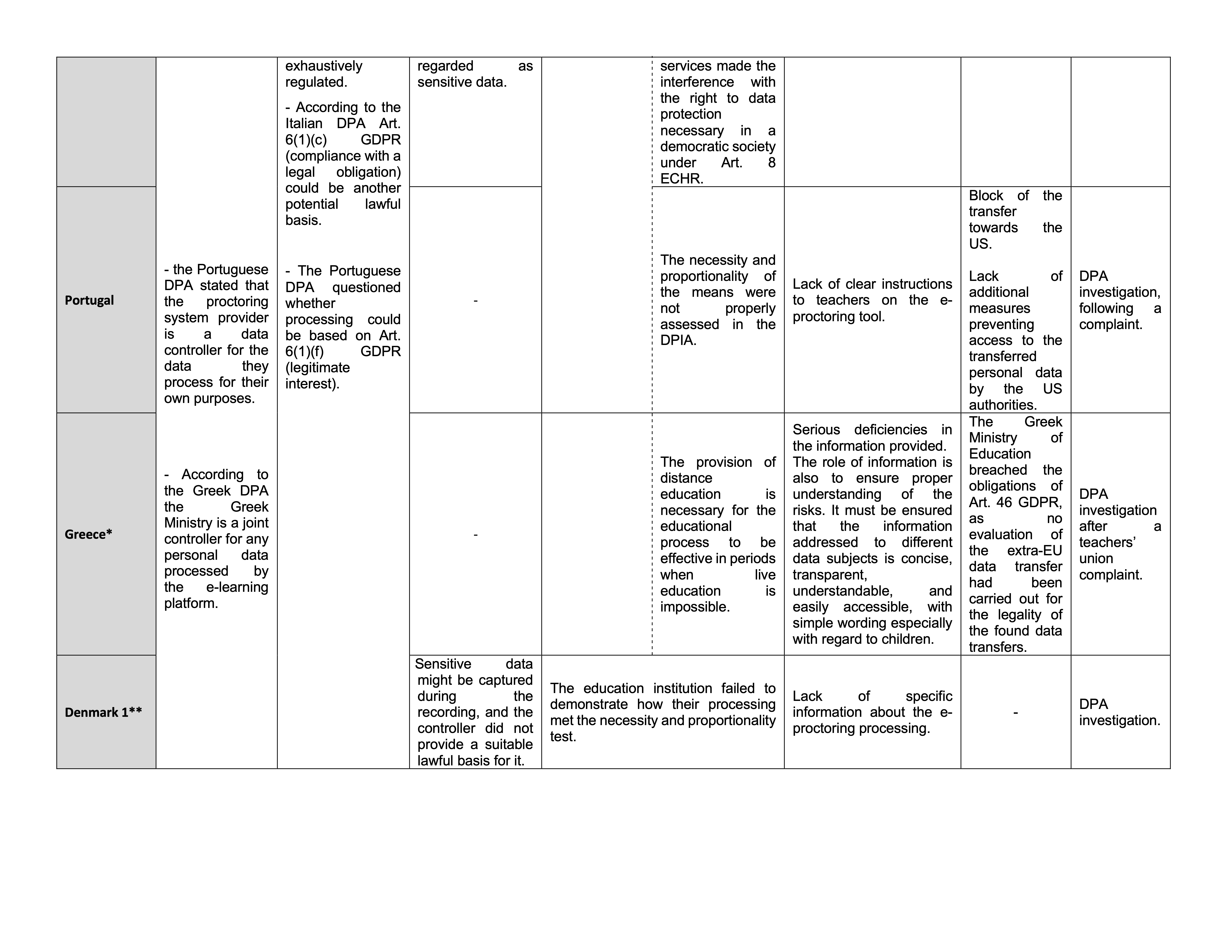

The table below includes the list of decisions summarising their main outcome.

Table 1. List of the e-proctoring cases with data protection claims and summary of the main outcomes of the decisions

|

Abbreviations |

Decision |

Type of invigilation |

Outcome of the decision |

Notes |

|

Denmark 1 |

Datatilsynet - 2018-432-0015 |

Automated e-proctoring system |

Violation of Arts. 5(1)(c), 9, and 13 GDPR |

Pre-pandemic case

Use of e-proctoring in a high school |

|

Denmark 2 |

Datatilsynet - 2020-432-0034 |

Recorded e-proctoring |

Processing in line with data protection rules |

Pandemic case

Use of the software at a HEI |

|

Germany |

OVG Nordrhein-Westfalen, Beschluss vom 04.03.2021 - 14 B 278/21.NE |

Recorded e-proctoring |

Claim dismissed for procedural reasons |

Pandemic case

Use of the software at a HEI |

|

Iceland |

Persónuvernd - 2020112830 |

Recorded e-proctoring |

Violation of Arts. 5(1)(a) and 13 GDPR |

Pandemic case

Use of the software at a HEI |

|

Italy |

Garante privacy - Ordinanza 9703988 - 16 Sep 2021 |

Automated e-proctoring system with flagging feature to spot cheating behaviours |

Violation of Arts 5(1)(a), (c), (e). 6, 9, 13, 25, 35, 44 and 46 GDPR

Violation of Art. 2-sexies of the Italian Data Protection Code (concerning the processing of special category data necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest) |

Pandemic case

Use of the software at a HEI |

|

The Netherlands 1 |

Rb. Amsterdam - C/13/684665 / KG ZA 20-481 |

Automated e-proctoring system with flagging feature to spot cheating behaviours |

Claim dismissed |

Pandemic case

Use of the software at a HEI

Judge for the preliminary injunction |

|

The Netherlands 2 |

Gerechtshof Amsterdam - 200.280.852/01 |

Same as in The Netherlands 1 |

Decision confirms the outcome of The Netherlands 1 |

Pandemic case

Use of the software at a HEI

Appeal of The Netherlands 1 decision |

|

Portugal |

CNPD -Deliberação/2021/622 |

Automated e-proctoring system with flagging feature to spot cheating behaviours |

Violation of Art. 5(1)(a), (b), (c) GDPR |

Pandemic case

Use of the software at a HEI |

28

In terms of general outcomes, the DPA decisions (with the only exception of Denmark 2) found at least one, but usually numerous, GDPR violations in the application of e-proctoring systems, notably with regard to transparency rules (Denmark 1, Iceland, Italy) or the safeguards on extra-EU transfer (Italy, Portugal). On the contrary, Dutch courts reached an opposing conclusion.

29

Hence, in order to have a clearer understanding of the state of the art of the case law concerning e-proctoring tools and data protection, it becomes relevant to comprehend the different points raised in the decisions, the arguments used, and the friction within the legal framework.

30

In the following subsections, we will focus on the four main points that emerge from the cross-analysis of the decisions on e-proctoring, notably: 1) the actors involved in processing for e-proctoring purposes and the allocation of responsibility between them; 2) the lawfulness of the processing; 3) the respect of the right to information towards the data subject when deploying the e-proctoring system; 4) the challenges of cross-border data transfer.

4.1. Accountable actors

31

The responsibility of universities has seen an undoubtedly horizontal consensus across all decisions from either courts or national DPAs. HEIs that have used e-proctoring systems for exam invigilation are all considered data controllers, with the e-proctoring system providers qualified as data processors. Such conclusions align with what has already been noticed regarding the relationship between the education provider and the third-party platform used for e-learning purposes. [29]

32

Remarkably, the Portuguese DPA articulated in greater detail the role, responsibility, and liability of the HEI and those of the e-proctoring provider, highlighting that the latter shall be seen as a data controller for the data they process for their own purposes (e.g., for the improvement of the service or for research). [30]

33

All the examined decisions look at the relationship between two actors: the HEI, on the one hand, and the e-proctoring platform, on the other. Even if not dealing with an e-proctoring case specifically, it is worth mentioning a Greek DPA's decision that goes a step further in analysing the responsible and liable actors in providing distance learning in schools. [31] The decision remarked that commercial e-learning service providers usually process data for purposes other than those set out by the HEI. This personal data collection and processing for their own distinct purposes qualifies these providers as data controllers for this function. Following this rationale, the Ministry of Education is the institution enabling and creating the conditions for this additional collection of personal data. Hence, in light of CJEU case law, [32] the Greek Ministry shall be considered a joint controller for the processing of personal data by the service provider. [33] While the reasoning is relatively succinct, and in reality, inconsequential for the Ministry itself as no further conclusions are put forward following this qualification, the recognition of the Ministry as a joint data controller for the data processing operations performed at the initiative of the private service provider, reveals the elevated responsibility of the State when favouring the implementation of distance learning tools.

34

Finally, all reviewed decisions and relevant opinions share the recognition of the responsibility of institutions in the decisions related to e-proctoring and remote teaching more generally. The recognition of a joint controllership between (private) service providers and (public) educational institutions, stressed by the Portuguese and Greek DPA, highlights the dependencies created between these two actors during the decision-making processes that lead to putting in place online education or e-proctoring systems. This “responsibilisation” of educational institutions shows the strong role of HEIs in enabling processing, making it possible for service providers to reuse educational data for autonomous purposes. [34] Moreover, it acknowledges the power dynamics at play throughout the establishment of big data-driven infrastructures. [35]

4.2. The lawfulness of the processing

35

The principle of lawfulness is a fundamental data protection pillar that protects data subjects, by requiring the processing to be compliant with the law, and necessary and proportionate to pursue a legitimate aim. [36] While there is a general agreement in all the analysed decisions towards the existence of a ground that can potentially legitimise the processing of personal data for e-proctoring purposes, the outcomes of the processing of sensitive data and the assessment of the necessity and proportionality of the means for ensuring the integrity of the exam diverge substantially.

4.2.1. Lawful ground(s) of e-proctoring processing

36

The first legal requirement that each HEI, as data controller for e-proctoring purposes, shall respect is the reliance on a lawful basis. [37] The majority of the cases found that the e-proctoring processing (whether live, recorded or automated) can fall within the umbrella of Article 6(1)(e) GDPR which qualifies data processing as lawful when “necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest”. [38] Whether the HEI is a public or a private entity, according to DPAs and judicial decisions, putting in place monitored online exams can be considered as “necessary to fulfil a task in the public interest”, i.e., to provide education, organise exams, and issue valid academic qualifications. [39]

37

The Italian DPA and the Dutch judge focused on the aspects of the processing that the law must regulate when Article 6(1)(e) GDPR is used. [40] In this respect, according to the Dutch judge of the first instance, it is not necessary “that the public task or data processing is exhaustively regulated in a law in a formal sense, it is sufficient that the main features are known in the law”. [41] Hence, the use of the automated e-proctoring tool was considered compatible with the Dutch legal framework. A more restrictive stance is taken by the Italian DPA, which stresses that the flagging system monitoring students' behaviour during the exam entails profiling. This processing creates specific risks for students (e.g., the exam can be invalidated) in violation of the principle of non-discrimination. [42] According to the DPA, when the processing relies on the lawful basis provided for by art. 6(1)(e) GDPR, such risks shall be properly assessed in a specific legislative provision. [43] The latter, however, was found missing in the Italian system, leading the DPA to invalidate the processing.

38

Contrary to the other decisions, the Icelandic DPA found the lawfulness of the processing in the legitimate interest of the HEI to ensure the integrity of exams and the quality of studies. [44] In the opinion of the DPA, such interests were not overridden by the students’ fundamental rights and freedoms, a fortiori because the students who did not have facilities at home were offered to take the online exam in the HEI buildings. However, the decision did not thoroughly discuss the feasibility of such an alternative. For instance, it emerges from the complaint that the student could not accept this option due to the health conditions of his spouse (who was a suspected COVID-19 contact). Such a situation then leaves more than a doubt concerning the actual chance of the person accessing the exam without the use of the e-proctoring system proposed by the university.

39

Finally, the Italian DPA also contemplates the possibility that e-proctoring might be grounded in Article 6(1)(c) GDPR, i.e., the necessity of the HEI to comply with a legal obligation. [45] However, this point is not further elaborated by the Authority.

40

A substantial agreement instead can be found in the express refusal of consent as a basis that can legitimise the processing of personal data when deployed by a HEI for e-proctoring purposes. This result is not surprising as it applies a consolidated interpretation of the consent requirements. [46] In particular, the manifestation of will shall be “freely given”, i.e. the data subject shall have a real choice whether to accept the processing for e-proctoring purposes, and, in this context, such a choice might be impaired by the imbalance of power between the students and the HEI, the lack of equivalent alternative modalities for the exam, or the inability to take the exam without agreeing to the further processing performed by the platform. For example, the Icelandic DPA stated that consent may not be a lawful legal basis for processing due to the nature of the relationship between the university and the students. For the Portuguese Authority, the consent was de facto imposed if students wanted to do the exam (hence, it was not freely given).

4.2.2. Processing of sensitive data

41

During the invigilation activity, the video recording can capture images or sounds revealing the ethnic or racial origin of the examinee, and the flagging system relies on the elaboration of the student's movements to identify suspicious behaviours. Whether such activities qualify as the processing of sensitive data, including biometric information, is a question that was answered quite differently in the analysed decisions. [47]

42

The first divergence concerns the classification of the information collected for detecting signs of cheating as biometric data. As known, biometric data are defined as those “personal data resulting from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person, which allow or confirm the unique identification of that natural person, such as facial images or dactyloscopic data”. [48] The definition reflects that biometric data are generated through the use of specific technologies that elaborate individuals’ features to identify (1:n biometric identification) or confirm (1:1 biometric verification) the data subject’s identity. [49]

43

In Denmark 2, the lawfulness of the processing of biometric data was raised but dismissed because it was proven that the system was not adopting any facial recognition technologies. Student IDs were checked randomly by the staff instead. In the Dutch cases, the judge of the injunction affirmed that the e-proctoring system was used for authentication purposes, [50] but it seems to emerge from the decision that the staff manually verified students’ identity at the end of the exam. With regard to the use of the flagging system to analyse students’ behaviour, the same decision quickly concluded that it did not entail any processing of biometric data. [51]

44

Different from the Dutch court, the Portuguese and Italian DPAs affirmed that the automated analysis of the students’ behaviour was processing of a “particularly sensitive nature”. [52] Both decisions stressed that such data were not used to identify or confirm the student's identity. [53] Nevertheless, they were used to profile students. [54] Without entering into the assessment of the legal nature of such data, the Portuguese authority stated that the processing was disproportionate. [55] On the contrary, the Italian decision specifically recognised that the e-proctoring system was generating, through automated means, a biometric template, i.e., a digital representation of the biometric characteristics of the students extracted from the video recording, and, as a consequence, the university was processing biometric data to verify the presence of the student during the exam and to spot anomalies in their behaviours. [56] Given the classification of the students’ facial images as biometric data, the Italian Authority applied the stricter regime established for special categories of data. [57]It concluded that, since there was no national provision to date that authorised the processing of such sensitive data for ensuring the integrity of exams, the processing was unlawful.

45

The second point of divergence in the decisions analysed concerns the classification of the information contained in the video recording, able to reveal the ethnic or racial origin, as sensitive data.

46

The Court of Appeal of Amsterdam (Netherland 2) is again very restrictive in its interpretation, excluding that the facial images—e.g., those contained in the student ID card—can trigger the protection reserved in the GDPR for special categories of data. [58] First, because the processing is not meant to process the sensitive characteristics; [59] and, second, because it is unlikely that the lecturers will discriminate against students based on those attributes. [60]

47

Similarly, the Danish DPA (Denmark 2) affirms that although “it cannot be ruled out that personal data covered by Art. 9 GDPR may be processed in connection with the monitoring of examinees’ computers” [61], the processing of such information is, in principle, unintentional. Hence, it dismisses the point of the university, which was declaring to rely on Article 9(2)(g) GDPR (i.e., the necessity of the processing for reasons of substantial public interest). Instead, the Authority recommended the controller to encourage students to avoid the sharing of sensitive data during the examination. [62] In a 2018 decision (Denmark 1), the DPA excluded as well the applicability of Article 9(2)(g) GDPR, considering its narrow scope (i.e., “which is namely assumed to be used, e.g., for processing of personal data for the purpose of health security, monitoring and alerting, prevention or control of communicable diseases and other serious threats to health” [63]). However, on that occasion it clearly stated that the controller should have identified another suitable lawful basis for the processing of sensitive data that can be accidentally recorded during an online exam.

48

The legal status of pictures and videos is not unproblematic. [64] There are only two direct references in the GDPR (Recital 51 and Article 4(14)) to them, and they are both related to biometric data. However, this is not the only special category of data that can be inferred from a picture. In its ‘Advice Paper on special categories of data’ [65], the Article 29 Working Party admitted the possibility that images of persons, like those captured by surveillance cameras, can reveal information about the ethnic origin or the health status of an individual and, as a consequence, can be classified as sensitive data. This initial interpretation, however, was not confirmed in the following Guidelines 3/2019 where the European Data Protection Board affirmed that video footage could be covered by Article 9 only if the processing is aimed at inferring special categories of data. [66] This ambivalence reflects the two main approaches that have emerged in the literature so far: a first approach (context-based) considers information in terms of special category of data and whether it is possible to derive the sensitive attribute from the circumstances of the processing; a second approach (purpose-based) retains that information can be considered under the umbrella of Article 9 when the controller aims to infer and use the sensitive characteristic. [67] The Netherlands and Denmark 2 cases seem to align with this latter approach.

49

However, the recent CJEU decision in OT offers some elements to reconsider the above mentioned assessment. [68] In this case, the EU Court went for a context-based interpretation, affirming that the publication of the spouse's name on the controller's website can indirectly reveal the sexual orientation of the data subject and shall be classified as a processing of sensitive data. [69] The Court, in particular, stated that the notion of special category of data shall be interpreted broadly to guarantee a high level of protection of fundamental rights, especially in cases where the data's sensitivity can seriously interfere with privacy and data protection. [70]

50

If the rationale is to ensure an enhanced level of protection for those data that can reveal sensitive information through an intellectual operation of deduction or comparison, we might assume that the e-proctoring activity consisting of the recording of a video that is automatically elaborated for spotting signs of fraud and that can be assessed by the lecturer, should be considered as a processing of sensitive data. Especially in this case, the intention to rely on the sensitive characteristics should be considered irrelevant: both humans and machines can be affected by biases and give rise to disadvantageous treatment in practice. [71] That is why, for example, written assignments are usually marked anonymously. [72] On the contrary, recommendations on the measures to avoid the unintentional sharing of sensitive data, as suggested in Denmark 2, might eventually be considered a minimisation strategy, which presupposes a processing of sensitive data and the need to be covered by one of the conditions under Article 9(2) GDPR. Indeed, even if some elements are easy to hide from a camera (and we should question whether such a request is legitimate in terms of freedom of expression), others are impossible to (e.g., physical characteristics revealing our ethnic origin).

51

Finally, it shall be mentioned that the Icelandic claimant was trying to introduce a point about the recording of another subject’s sensitive data, potentially captured during the videocall. In that case, while the student was taking the exam, his spouse was having a remote medical consultation, and the claimant was worried that the conversation could have been recorded. The issue was dismissed for procedural reasons (although the DPA noticed that, considering the circumstances of the exam, the recording of the data subject’s wife would have been unlikely). [73] It is, however, another sign that shows how the deployment of an e-proctoring process can be intrusive, breaking the boundaries between the public and private spheres, revealing students’ private life and personal circumstances.

4.2.3. The necessity and proportionality of the e-proctoring processing

52

Overall, with the clarifications mentioned in Section 4.2.1, the examined decisions recognise that Universities can use e-proctoring systems to pursue the legitimate aim of ensuring the organisation and integrity of exams during the pandemic. However, for the processing to be legitimate, its operations shall be necessary and proportionate in relation to its purpose.

53

With regard to this issue, the French DPA adopted some general guidelines in the document “Surveillance des examens en ligne : les rappels et conseils de la CNIL'' [74], outlining a few case scenarios and examples. The DPA considered that real-time video surveillance or snapshots of audio/video during examinations do not appear prima facie disproportionate. On the contrary, tools that allow the remote control of students’ computers or the use of facial recognition systems might not be proportionate to the purpose of online examination.

54

All the decisions acknowledged that the pandemic forced universities to consider alternative assessment methods to traditional ones due to the impossibility of organising exams in person. [75]

55

The Icelandic DPA recognised that the e-proctoring processing was necessary to prevent exam fraud and ensure the reliability of evaluations and, thus, the quality of studies during the pandemic. [76] A similar conclusion was reached in Denmark 2. The Danish Authority acknowledged the assessment of the need for examination supervision performed by the HEI in relation to its courses, finding that the university adopted the e-proctoring tool only for one exam where it was crucial to ensure that students did not receive any external help (since there was only one correct identical answer and students did not have to explain how they reached that solution), [77] chose the least intrusive e-proctoring program, and had a proportionate storage period (21 days). [78]

56

The Dutch judge considered the potential interference of the use of e-proctoring tools with the right to data protection as necessary in a democratic society according to Article 8(2) ECHR because of the restrictions adopted during the COVID-19 period and the need to ensure the provision of education (which was considered in its economic relevance as well). [79] Moreover, the Court affirmed that the interference with Article 8 ECHR was proportionate due to the absence of alternative e-proctoring tools which were equally efficient at preventing fraud as the one adopted by the university in its case.

57

The rest of the decisions came to an opposite outcome. [80] The Italian and Portuguese Authorities recognised that the necessity and proportionality of the means were not properly considered in the HEIs' Data Protection Impact Assessment (“DPIA”).

58

The Italian DPA, in particular, noticed the excessiveness of: 1) the data collection (the system did not simply inhibit some functions on the student’s computer, but it also generated information based on their behaviour which was not considered strictly necessary for ensuring the validity of the exam), and 2) the retention policy (initially five years, reduced to one during the proceeding). [81] These elements led the Authority to declare the violation of the principles of minimisation, storage limitation, and data protection by design and default.

59

Reaching a similar conclusion, the Portuguese DPA started from the consideration that the processing involved a massive collection of data for the purposes of profiling and monitoring students. However, there was no assessment of the appropriateness, necessity, and proportionality of such a processing in relation to the general objective of ensuring the integrity of the exams. Furthermore, the scoring system assessing deviant behaviours was considered fairly opaque, making it impossible to evaluate the necessity and proportionality of the collection. Thus, the DPA concluded that the data minimisation principle was not respected. [82]

60

All in all, the examined decisions investigated the necessity and proportionality of the processing’s means, with different outcomes. This is not surprising, considering that this assessment should entail a case-by-case evaluation.

61

While the break of the pandemic was, in principle, considered a reason for the necessity of the interference with the right to privacy and data protection, the concrete implementation modalities of the e-proctoring tools led DPAs to sanction the most intrusive e-proctoring processing, i.e., those entailing students’ profiling or the calculation of the “cheating score”. The only exception is the Dutch case, where the automated e-proctoring was indeed admitted. Here, however, the decision seems to derive from a procedural reason rather than a substantive one, i.e., the lack of adequate evidence provided by the claimants. The Dutch judges considered, in fact, that the students did not furnish suitable and less intrusive alternatives, able to overturn the university’s assessment.

62

On a more general level, the DPIA proved to be a crucial document that was extensively used by the majority of DPAs to evaluate the legitimacy of the controllers' choices critically and, in particular, the necessity and proportionality of the measures adopted. For instance, even if the case was not focusing on e-proctoring but on distance education more generally, the Hellenic DPA consistently highlighted that the provision of proof in support of the necessity and proportionality of the COVID-related measures taken by the Ministry of Education should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, especially due to the diverse ways in which these measures have the potential to impact different educational tiers. The evaluation on this case-by-case basis is expected to be performed (and subsequently proven) in the DPIA document. The engagement with this document is less evident in the Icelandic and Dutch decisions, where the Authority and the judges checked the performance of the DPIA but without an extensive engagement with the merit of the assessment.

4.3. The transparency of the processing

63

One critical factor that led to the invalidation of the majority of e-proctoring processing was the implementation of the principle of transparency. Such a principle, enshrined at Article 5 GDPR, requires the data controller to inform the data subject about the key aspects of the processing—including its risks—in a clear and timely manner (not only at the beginning of the processing operations but also after a data subject’s request or in the case of data breach affecting data subjects rights). [83] The analysis of the cases reveals that universities largely failed in their duty to inform students about the processing occurring during e-proctoring.

64

The Danish (in Denmark 1), Italian, and Icelandic DPAs highlighted serious deficiencies in the content of the privacy policies provided to students. In particular, such cases pointed out the lack of adequate information about crucial aspects of the processing, such as the modalities of the monitoring, [84] data subjects’ rights, [85] and profiling. [86]

65

The Portuguese and Icelandic DPA also emphasised the lack of clear instructions for teachers on the conditions and features of the respective e-proctoring tool. The Icelandic Authority considered that the training and education about the system was a complementary aspect of the duty to inform the student under Article 13 GDPR. [87] Meanwhile, the Portuguese Authority stated that the lack of instructions to lecturers introduced an excessive margin of discretion on staff, denoting a scarce delimitation of the purpose of the processing and a lack of data minimisation by the controller. [88]

66

The Italian DPA noted further violations of the principle of transparency, following the guidelines of the WP29. [89] First, noticing that the privacy policy used general formulas in relation to data storage, the DPA admonished the need to detail the specific storage period for the different categories of data processed. Second, in relation to the lack of relevant information concerning the transfer of data extra EU, the DPA affirmed the need to inform the data subjects about the country where the data were exported, the lawful ground for such a processing, and the specific safeguards for them. [90] Third, even though the DPA recognised that the e-proctoring system was not fully automated (hence, excluding the application of Article 22 GDPR) [91], it recalled the importance of informing data subjects about the risks of the processing in a meaningful way, avoiding situations where they are taken by surprise. In practice, this means that the controller shall make the individual aware of the logic of the e-proctoring algorithm and its consequences. [92]

67

Interestingly, the Portuguese case takes a different stance on the application of Article 22. The Lusitanian Authority, examining an e-proctoring tool similar to the Italian one, doubted that the intervention of a member of the staff, in case of a notification of anomalies in the student’s conduct, could be considered a genuine human intervention. Given the lack of instructions to teachers and the lack of transparent information about the parameters used by the algorithm to signal deviant behaviours, the staff would have little elements to draw their own conclusions. [93] It did not elaborate further on Article 22 GDPR (for instance, about the existence of the conditions under Article 22(2) GDPR), but it alluded to the lack of remedies for the students to contest the decision. [94]

68

While both the Italian and Portuguese Authorities confirmed the need to inform data subjects about the logic and parameters of the e-proctoring algorithm, the Court of Appeal of Amsterdam quickly dismissed the possibility that the university should provide full insights into how the suspected behaviour is detected. In the opinion of the Court, such information could actually conflict with effective fraud prevention. [95]

69

Finally, with reference to the form of communication, the Italian DPA provided additional indications. It condemned the adoption of vague formulas (e.g., ‘by way of example but not exhaustive’) in the text of the privacy policy, the use of hyperlinks that do not lead to the relevant page, and the use of layered notices not accompanied by the full privacy policy. Moreover, the DPA had the occasion to specify that the mandatory disclosures required under Article 13 GDPR cannot be fulfilled by providing information to the students' representatives. Each and every data subject should be targeted instead.

70

In Denmark 2 the information provided by the university to the students was overall positively evaluated. According to the DPA, the specific target was reached with a letter describing the e-proctoring processing in a “concise, transparent, easy to understand, easily accessible form, and in a clear and simple language” [96], and the letter was in addition to the general information notice that individuals receive at the beginning of their studies (which remains accessible on the university communication platform). [97] However, the Danish DPA pointed out that the university should have specified that the system records the browsing activity during the exam and that it is able to capture sensitive information, encouraging the HEI to fix such issues.

4.4. Extra-EU data transfer

71

Many European DPAs have expressed their concerns and issued decisions regarding the legitimacy of occurred data transfers outside of the EU in the context of e-proctoring.

72

The Italian DPA has underlined that many transfers to the US of data collected during remote teaching activities lacked an adequate lawful basis. [98] This trend was confirmed in the e-proctoring decision at stake. The DPA ascertained that the transfer was based on standard contractual clauses (“SCCs”). However, the technical and organisational measures were not sufficiently described in the contract by the importer and, as a consequence, were not in line with the requirements established by the same SCCs, as data subjects may not rely on such measures. [99] Similarly, the Portuguese DPA underlined the lack of an appropriate transfer mechanism with respect to two e-proctoring applications used by the university. According to the national supervisor, the university did not adopt the additional safeguarding measures to protect data in line with the Schrems II principles. [100]

73

Remarkably, the Dutch courts in Netherlands 2 rejected the claim made by the plaintiffs with regard to the extra-EU data transfer and highlighted that they did not plausibly demonstrate that anyone not authorised by the university to view the video and audio, such as the service provider itself or US intelligence agencies, could gain access. [101] This appears to be quite a peculiar perspective, since the GDPR requires—in first stance—proof of the establishment of adequate safeguards for the protection of transferred personal data. The GDPR’s approach is that of minimising the risk of access, by preventing access episodes through enacted safeguards. Along these lines, the Dutch Court appears to postpone the focus of the analysis to a secondary and pathological moment that the GDPR intends to approach through anticipatory protection tools. Hence, in line with the GDPR’s objectives, the Court should have rather focused on the proof of safeguards instead on the proof of access. This is the approach taken in the Italian decision instead.

74

The cases mentioned above illustrate the concrete challenges for transferring data outside of the EU after the invalidation of the Privacy Shield. The DPA decisions are not isolated cases but follow a series of other important interventions in the sector of edTech. The Austrian DPA, for example, found that Google analytics services used for educational monitoring purposes were violating Article 44 GDPR, for they did not ground outside EU data transfer in one of the legal bases envisaged by the GDPR. [102]Similarly, the CNIL deemed the SCCs relied on by Google to be ineffective in so far as these did not “prevent access possibilities of US intelligence services or render these accesses ineffective” [103]. The transfers enacted by Google were thus considered to undermine “the level of personal data protection of data subjects as guaranteed in Art. 44 of the GDPR”. [104] The Danish government has announced a ban on Google Workspace and Chromebooks in Danish schools, noting that data processed from online education activities could be accessed by non-EU authorities in manners inconsistent with EU data protection law. [105] More recently, a data governance study in UK schools showed that little has changed since the invalidation of the EU-US Privacy Shield, and many companies continue to transfer education data to the US. [106]

75

It is yet to be seen how the new draft US-EU adequacy decision “Data Privacy Framework”, under discussion within the EU institutions, will address the concerns that have emerged so far. [107] In this respect, the EDPB raised several concerns in its Opinion 5/2023, restating the presence in the draft of existing issues related to "the rights of data subjects (e.g. some exceptions to the right of access and the timing and modalities for the right to object), the absence of key definitions, the lack of clarity in relation to the application of the DPF Principles to processors, and the broad exemption for publicly available information". [108] Similar concerns were expressed by the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (“LIBE”) in a draft motion for a resolution on the proposed adequacy decision, pointing out that, despite the changes introduced in the US legal order, the US system does not still grant an equivalent level of data protection. [109] Hence, the LIBE called on the Commission to continue the negotiations and urged not to adopt the draft of the adequacy decision presented on the 13th of December 2022. The European Parliament confirmed this view in its Resolution on the adequacy of the protection afforded by the EU-US Data Privacy Framework, urging the Commission "not to adopt the adequacy finding until all the recommendations made in this resolution and the EDPB opinion are fully implemented". [110]

76

This situation concerning the EU draft transfer inevitably highlights the technological dependence of HEIs on third-party providers subject to foreign law and the risks associated with such a choice. [111] Therefore, it is crucial to reflect on the possibility that edTech tools could be developed by European public players, who shall take into account—by design—the needs of the institutions and the EU values embedded in the Charter of fundamental rights and CJEU case law.

5. E. Countering e-proctoring systems with GDPR collective action

77

GDPR enforcement processes—either through the exercise of data rights before the data controller, or through recourse to a DPA or courts—are key in understanding how e-proctoring systems can be inspected, challenged, and lawfully restrained. Whether at a university or an e-proctoring service provider level, personal data processing left unchecked risks, principally, harming students’ fundamental rights. It is thus important to inspect the degree to which students and other (collective) entities are empowered to challenge e-proctoring systems bringing claims in front of the relevant authorities to contest the exclusionary and intrusive effects of online invigilation.

78

As our above analysis shows, e-proctoring systems can and have been challenged in both national courts and data protection authorities with relative success. It is interesting to note that on many occasions, universities were ordered to stop using specific e-proctoring software due to the GDPR violations observed by the DPAs. To this day, national courts have not delivered similar decisions.

79

Student complaints vis-a-vis the national DPAs is what instigated the decisions against the use of e-proctoring systems in Italy, Portugal, and Iceland. As we briefly presented above and as summarised in the Annex, students were able to raise arguments ranging from GDPR violations (unlawful consent to the processing of personal data, etc.) to violations of fundamental rights such as privacy and data protection. [112] These cases stayed well within the realm of individual direct action that aims to counter harms experienced by students in the deployment of e-proctoring systems.

80

Personal data protection normative frameworks tend to centre around the individual. This perspective is an important dimension of the way in which data protection law ensures (levels of) control over personal data. Yet, there are different ways in which data protection law—and the GDPR in particular—enables collective empowerment beyond the individual. While understudied in scholarship and underused by policymakers, judges, and authorities, it is vital to explore GDPR collective action as a tool to challenge e-proctoring systems, especially as it has become widely accepted that data-driven technologies often provoke harm beyond the individual level.

81

The GDPR creates the procedural framework within which individuals can claim redress of individual harms incurred to each data subject respectively, but through acting collectively. [113] The recent Ola/Uber cases [114] show how these types of processes can empower groups of individuals when they exercise their rights in a coordinated manner. The Oracle/Salesforce case [115] is another stellar example of this understanding of collective action because its reasoning goes well beyond the limited number of individual claimants. This procedural framework requires a representative organisation or simply the coordination of numerous individuals, who bring one single procedure forward. Collective action can also refer to a single action on behalf of a group of individual data subjects operating to obtain a collective gain.

82

In the case of e-proctoring, we believe that GDPR collective action can be viewed as one available tool to tackle and counter harms suffered by specific groups of students or even by the student body as a whole. However, their (limited) exercise has not been particularly successful.

83

Collective student action has been a key instrument for ensuring the broader impact of the desired outcome. In Germany, for example, a complaint contesting the use of e-proctoring software was filed jointly by a university student and a digital rights non-profit organisation (the Gesellschaft für Freiheitsrechte (“GFF”)). [116] The complaint regarded the storage and processing of video and screen-recorded data by the e-proctoring software that the university chose for conducting student exams during the lockdown. The requested injunction failed to produce the desired outcome of restricting the storing of exam video recordings, as the motion was denied by the Court on the basis of procedural elements, preventing the examination of substantive aspects. [117] In particular, the Court stated that it could not address the lawfulness of the processing in the emergency proceeding. An overview of the injunction reveals that the urgent procedure which was chosen due to the student circumstances was not the appropriate juridical forum, especially when the objective was to produce an impactful decision that would contribute to counter surveillance and e-proctoring system normalisation in HEIs. This case is a representative example of litigation efforts to ensure a strategic outcome against the use of e-proctoring software.

84

When thinking about the effects upon individuals of powerful systems mediated through data-driven technologies, strength in numbers is critical. For this reason, GFF is decidedly attempting to create the necessary conditions for introducing collective action representing multiple students. Namely, the NGO has launched a public call looking for affected students. According to the call, GFF “want(s) to win fundamental decisions against excessive surveillance through online proctoring - and the best way to do that is with several cases that illustrate the problem”. [118]

85

Similarly, in Netherlands 1 and 2, rather than individually instigated student complaints, it was the representative body of students who launched a lawsuit against their university challenging the decision and the conditions of use of e-proctoring systems for online invigilation. The representative student council body contested the unlawfulness of the personal data processing, the discriminatory effects of the software, and the lack of student participation in the decision-making process regarding the use of e-proctoring systems for exam invigilation. This case is among the few that were brought forward by students on the basis of multiple GDPR violation claims.

86

Interestingly, among all the cases examined, the student council was the only one challenging the institutional decision-making processes that led to the introduction of the e-proctoring systems. These processes did not involve the input and feedback from the student council, characterised by the university as “unsolicited advice” on the use of online proctoring. [119] The Amsterdam Court in Netherlands 2 rejected the student council’s claims invoking the internal regulations that permit such ‘emergency’ decisions to be taken unilaterally by the administrative body of the university without having to necessarily consider the input of student representative bodies. Remarkably, but not surprisingly since this was a civil litigation, the Court put the responsibility to determine, describe, and explain all available alternatives to all types of invigilation processes that are occurring in the context of student exams on the claimants, i.e., student council. [120] Ιn sum, this means that the Court conceded that the student council's input was not necessary in the decision-making process regarding e-proctoring systems; at the same time, the Court decided to put the burden of explanation (and proof) on the advantages of alternative solutions to that same student council.

87

Finally, the Dutch Court in Netherlands 2 recognised the admissibility of the student council as a claimant in this case. However, it did not justify the decision based on the GDPR procedural standing rules nor clarified whether the claimants represented the university’s students in their collective interests vis-a-vis the GDPR violations in question. This lack of clarity is but one example illustrating the need for legal and procedural certainty in collective action cases with GDPR-based claims.

88

Similarly, in Greece, following a complaint filed by the association of teachers and even though the decision addresses remote teaching in general and not e-proctoring specifically, the DPA delivered its opinion highlighting the constitutional duty of the state to ensure the provision of education. [121] This duty, according to the DPA, provides the necessary precondition to any decision that is geared towards fulfilling that obligation. As mentioned in Section D.I, the complaint was filed with the Greek DPA by the private schools' teachers' union. It is noteworthy that the DPA found the union to not have the standing to file such a complaint because it did not operate under a specific mandate. [122] The lack of clarity about the need for representation mandates with regard to the defence of individual and collective interests and the inconsistencies in collective representation at national levels are creating the space for inefficiencies of GDPR enforcement. [123]

89

Overall, we contend that collective action cases instigated by students and/or represented by student bodies and other similar organisations help (re)shape the public interest objectives of HEIs to a participatory model that includes student voices in determining student interests as a whole. In this context, the GDPR can constitute a solid legal basis for these actions because of its potential to uncover harms and inequalities. This has certainly proven to be true in the Ola/Uber cases and can follow similar paths in contesting e-proctoring systems. However, existing disparities in national collective action legal frameworks could limit the full potential of these mechanisms.

90

Beyond the data protection framework, equality law can be distinctly mobilised for the same purposes, as shown in a recent case in the Netherlands. In the next Section, the paper will present the first case contesting the discriminatory effects of the identity recognition feature of an online invigilation software, discussing the remedies available to challenge e-proctoring practices under the EU anti-discrimination legal framework.

6. The right to non-discrimination and e-proctoring

91

The above analysis reflects on the effectiveness of data protection tools as forms of accountability and assessment for e-proctoring systems used by public educational institutions. Despite the potential of the GDPR as a frame of reference and enforcement tool to protect human rights, the above-mentioned decisions did not go beyond data protection concerns. For instance, the discriminatory risks brought by e-proctoring were rarely put forward and discussed. However, such risks have become more and more pressing over the past few years.

92

As mentioned in Section 3, many concerns have been raised about the error rates of the e-proctoring’s facial recognition systems used for authenticating students leading to discriminatory effects against, such as black examinees. [124] Those students, for instance, have reported trouble logging into the virtual environment or were only able to do so when shining additional light on their faces. [125]

93

An e-proctoring software was used by the California bar for the admission exams organised remotely during the COVID-19 lockdown. Three students with disabilities sued the California bar because it refused to modify its remote proctoring protocols, which were making it impossible for disabled test-takers to efficiently sit the remote exams. [126] In Gordon v. State Bar of California, [127] the Court rejected the preliminary injunction because it did not recognise a concrete harm in the proctoring processes especially vis-a-vis the broader COVID-19 crisis. These are but some examples of reported exclusion. [128]

94

It is important to note that the discriminatory effects of e-proctoring systems are often linked to the facial recognition software and the room scan features of e-proctoring. Bias in these types of algorithms is not new, leading some academic institutions to reject or cease the use of e-proctoring systems citing accessibility and equality concerns. [129] However, as evidenced by our case law analysis, contesting e-proctoring systems has shown its limitations because the examination of data protection and privacy compliance did not always consider potential harmful, discriminatory effects. [130] For instance, while the plaintiffs did mention discrimination concerns in their litigation in the Netherlands 2 decision, barely any reference to this was provided. In particular, the students argued the potential for discrimination based on the protected characteristics of students recorded for the purposes of identification and online invigilation that might be revealed such as race or religion. However, the Court remarked that it does not appear to be possible that the material recorded will be used for discriminatory purposes but does not provide further arguments for such reasoning.

95

So, the question remains: what are the tools available to counter the discriminatory effects of e-proctoring systems? In examining this, we should also stress that while anti-discrimination law could constitute a suitable tool for software affecting a protected category, other groups (e.g., people with limited internet access) are not directly covered by this legal instrument.

96

The discriminatory effects caused by the facial recognition system were not specifically discussed in the decisions analysed in the previous Sections (see Table 1) because it was ascertained that students’ identities were manually checked by the examiners.

97

However, if a facial recognition system was adopted, the GDPR might have offered some (limited) grip to combat algorithmic discrimination. Article 22 GDPR might apply, but on the condition that the processing was solely automated with no meaningful human oversight. Moreover, the DPIA would offer the chance to assess and address discriminatory effects. [131] However, these sections of the DPIA often remain not sufficiently investigated.

98

Beyond the GDPR, anti-discrimination law is another relevant framework whose impact against e-proctoring systems is soon to be tested for the first time in the Netherlands. [132] During the submission of this paper, the first European case of an anti-discrimination complaint against the facial recognition system of an e-proctoring tool was filed by a student within the College voor de Rechten van de Mens (the “Netherlands Institute for Human Rights”, hereinafter “NIHR”). [133] According to the submitted complaint, [134] the student had difficulties logging into the e-proctoring system because the facial recognition software could only detect her face with the light pointing straight at her. The student claimed that this software’s inability to detect black people, especially when a public HEI mandates the use of this software, was discriminatory. The university’s initial response to the student was to attempt to decouple the student's skin colour from the factors considered by the facial recognition proctoring algorithm mainly due to the lack of proof of the existence of such a link. The response to the internal complaint was that “they cannot establish an objective link between the student's skin colour and whether or not the digital surveillance system is functioning properly”. [135] Against the backdrop of this case, it is useful to evaluate anti-discrimination laws as defensive tools against harms caused by e-proctoring algorithmic systems.

99

As explained by the complaint filed by the student, the Dutch anti-discrimination law qualifies indirect discrimination as whenever any apparently neutral provision, standard or practice related to people of a particular religion, belief, political opinion, race, gender, nationality, heterosexual or homosexual orientation or marital status is particularly harmful when compared to its effect on other people. [136]

100

The NIHR published an interim judgement on the 7th of December 2022. [137] It found that the facts presented by the student were sufficient for a presumption of indirect discrimination based on race, because: a) she was disadvantaged by the anti-spying software; and b) there is academic research showing that facial detection software generally performs worse on people with darker skin colours. [138] The NIHR applied existing legislation according to which, when there is a presumption of discrimination (so-called prima facie discrimination), the burden of proof shifts to the defendant, who must justify the use of the software. [139] In this respect, the NIHR concluded that the university had not provided sufficient evidence to do so. Hence, it gave ten weeks to the university to further substantiate its defence and reserved its final decision. As some authors have stressed, if the algorithm is a black box, it might be quite challenging to provide evidence of the lack of discrimination. [140]

101

Universities have a duty under anti-discrimination law to ensure that the practices—including e-proctoring features—are not unduly disadvantageous to any students before implementing them. To this end, they should choose a provider who will ensure this condition is satisfied.

102

In GDPR terms, this duty of care can be reflected in the application of the fundamental principles, such as accountability, fairness, and integrity. The principles of proportionality and necessity may play a significant role in assessing the lawfulness of the processing through e-proctoring software, also in relation to the assessment of discrimination risks. Moreover, it would be interesting to see national courts or DPAs assessing the existence of discrimination through the DPIA and the lens of the fairness of processing, a principle affirmed by Article 8 CFREU and Article 5 GDPR. This assessment could take place, for instance, when contesting a biased e-proctoring system that involves biometric authentication to sign in.

7. Final remarks

103

Over the past three years, many concerns have been raised in relation to the risks and situations of harm of e-proctoring implementation at universities during the pandemic. [141] Such concerns have been voiced and examined across Europe in a series of cases that were collected and critically analysed in this paper. In this final Section we summarise the legal takeaways of the analysis and pinpoint the more systemic issues that need to be addressed in relation to e-proctoring, and edTech more broadly.

104

Even if e-proctoring will not generally be needed by traditionally non-distant HEIs anymore (unless new emergencies arise), it might still be considered by those universities which are offering online programs, or which want to keep online assessments as an option. Hence, it is relevant to understand to what extent e-proctoring tools shall be used or implemented by universities in the post pandemic world.

105

The case analysis shows that Courts and Authorities i) took the emergency situation into account in their decisions, ii) identified key problematic issues in the use of e-proctoring tools from a data protection point of view; and iii) non-discrimination issues emerged later, and the litigation is, at the moment, less developed when compared to data protection.

106

With reference to the first aspect, the situations of urgency and emergency faced by HEIs due to the COVID-19 lockdowns entered the balancing exercise to assess the legitimacy of alternative exam measures and, in some circumstances, led to the justification of the adoption of remote proctoring. However, now that the peak of COVID-19 is over as a global health emergency it is important that universities review the measures implemented during the past three years and abandon those that are no longer necessary or proportionate.

107

Secondly, data protection authorities found several points of friction between the deployment of remote invigilation and the GDPR, leading, in the majority of cases, to the block of the processing. For instance, the most invasive features, including the profiling of students for flagging suspicious behaviours, were banned by DPAs on a number of grounds, such as the lack of proportionality or lawful basis for the processing of sensitive data or for the extra-EU data transfer.

108

Different lines of reasoning were followed by civil courts. Dutch judges, in Netherlands 1 and 2, generally admitted the legality of the use of automated e-proctoring during the pandemic, confirming the assessment performed by the university.

109

When the processing did not involve the controversial flagging feature, all DPAs stressed some issues in the implementation of the transparency measures adopted by the universities to inform students.

110

Indeed, the lack of information provided to students and staff was a critical deficiency highlighted by the supervisory authorities. This situation might be a consequence of the general opaqueness of the system (noticed, for instance, by the Portuguese DPA). The lack of information on the “cheating score” and the way it should be reviewed by examiners raises several questions as to the effective presence of the “human in the loop” in this kind of situation. Hence, where there is no authentic human oversight, Article 22 GDPR should find application and this will cast more than a doubt about the possibility to justify an automated decision, based on profiling, against the students on any grounds of Articles 22(2) or (4) GDPR.

111

DPAs and Courts developed divergent reasonings on two further important issues that can put into question the use of e-proctoring tools: 1) the scope of Article 6(1)(e) GDPR and to what extent the processing performed in the exercise of a public task should be sufficiently specified in a law or regulation; and 2) the assessment of the legal status of pictures and biometric templates collected or generated during e-proctoring operations.

112

With reference to the first point, the Italian DPA convincingly points out that the profiling feature and the flagging system raise new risks for the protection of fundamental rights that should be adequately considered in a specific law or regulation. The necessity to guarantee the integrity of exams and degrees is indeed a task carried out in the public interest by HEI, but the legal framework in place reflects a situation where the exams were supposed to be organised in a more traditional fashion. Hence, unless this specific processing is adequately regulated in a law, detailing the limits and safeguards of it, the feature to monitor the behaviour of students during the online exam might not be grounded on a lawful basis (at least in Italy, the flagging system was declared to be in violation of Article 6 GDPR).

113

On the contrary, the Dutch judges seem to have adopted a lighter interpretation of the requirements needed under Articles 6(1)(e) and (3) GDPR or, at least, they did not consider the e-proctoring data processing particularly intrusive as to justify a more tailored regulation. Hence, given these different interpretations, this point might be contested in a future litigation or investigation before a data protection authority.

114

With regard to the second aspect—the assessment of the legal nature of pictures and videos collected during the exam, the decisions raise some further issues concerning the notion of biometric and special categories of data.

115

All the cases examining the flagging systems excluded that the processing of pictures to assess the students’ behaviours was used to identify or verify the identity of individuals. The definition of biometric data and its classification as a special category of data in the GDPR is quite narrow and it might not include situations like the one here, namely biometric categorisation. [142] Nevertheless, as pointed out by the Italian Authority, when the system generates a biometric template, it is performing a processing that is preparatory to the identification and verification of the identity, even if the data is not used for this purpose in the end. [143] In other words, following the DPA’s logic, the attitude of the template to “allow or confirm the unique identification of that natural person” (Article 4(14) GDPR) can meet the definition of biometric data.

116

A different question is whether the processing of biometric data that is not used to uniquely identify an individual will attract the regime designed for the special category of data. As pointed out in Section 4.2.2, the reference to biometric data is quite narrowly crafted in Article 9, and the GDPR seems to have drawn a distinction between identification and verification based on the level of risk that these activities pose to individuals. [144] Nevertheless, many scholars have been quite vocal about the pitfalls of this classification, considering that —for whatever purpose a biometric data is used—the characteristics that can be extracted from it still retain a considerable potential to enable the identification of individuals or negatively affect them. [145] Moreover, and as we have already highlighted, biometric data is one of the areas where Member States can intervene to specify further conditions for the processing. Hence, biometric classification performed with some e-proctoring tools could entail the processing of special categories of data (as affirmed, for example, in the Italian case).

117

As for the pictures not transformed into biometric data, but collected and stored during the invigilation procedure, we have seen that these have the potential to reveal sensitive attributes related to ethnic origin, religious beliefs or political opinions. The legal nature of such data has been debated, but the CJEU has recently confirmed a broad understanding of the notion of sensitive data: if it is possible to infer the sensitive characteristics from the context of the processing, data should be treated as a special category and protected accordingly. This interpretation would be able to address most of the discriminatory concerns as data controllers will have to properly assess the disparate impact for students in the DPIA and, if the system is adopted, appropriately justify their choices and safeguards in place (for instance, how to train the examiner who reviews the flagged videos or how to explain how the “cheating score” is calculated).

118