Untitled Document

urn:nbn:de:0009-29-55610

1. Introduction*

1

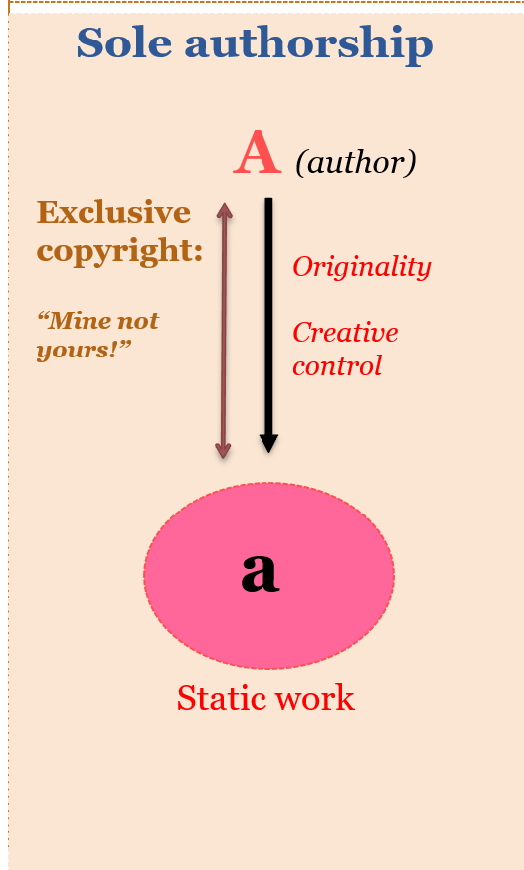

Since its inception, the evolution of modern copyright law has been characterized by a dominant narrative of exclusive property rights. [1] Exclusivity can be defined as the quality of a legal right in a tangible or intangible good that precludes any person other than the rightholder from benefitting from the utilities of that good. [2] The essence of copyright law is the exclusive copyright that is granted to an author over the work created by them. The exclusive copyright enables the author to reserve the utilities of that work (e.g. reproduction, adaptation, communication to the public etc.) to their own individual enjoyment (i.e. ‘mine not yours’). It further grants the author an affirmative claim to prevent any other person from benefitting from the utilities of the copyright protected work without their authorization. [3]

2

The exclusivity-based narrative is reinforced by copyright’s individualistic conception of authorship that frames authorship as an individual relationship subsisting between a specific person (i.e. author) and the expression (i.e. work) that is created by that person (or originates from them). This individualistic conception of authorship is at the core of copyright law’s perception of an author as a solitary romantic genius who is the sole creator of unique works that originate from their own individual intellect. [4]

3

This paper posits that Wiki authorship—an emerging model of collaborative creation in the digital humanities—challenges this individualistic conception of authorship and consequently the dominant exclusivity-based narrative of copyright law. It further argues that, in order to give legal expression to the relationships that exist among authors engaged in the creation of a work under the Wiki authorship model, it is necessary to introduce a parallel notion of an ‘inclusive’ copyright to the copyright law toolbox. In doing so, it proposes a paradigm shift in the conception of copyright as a tool for individual ownership (‘mine not yours’) to a property right that is capable of collective ownership by an open community of rightsholders (‘mine and yours’).

4

The notion of an ‘inclusive’ copyright that is advanced in this paper, is based on the concept of an ‘inclusive’ property right proposed by Dusollier. [5] Dusollier envisages an inclusive property right as a legal relationship between a person and a tangible or intangible good that is characterized by the absence of a power of exclusion and a plurality of persons being included in the collective use of that good. [6] Accordingly, Dusollier’s concept of an ‘inclusive’ property right is based on two key characteristics: (a) a legal right to a good that is held by a plurality of persons which is characterised by the collective enjoyment of the utilities of that good; (b) an absence of a power or privilege on the part of any person to exclude an owner of the inclusive property right from benefitting from the utilities of the good. ‘Inclusivity’ can thus, be described as the quality of a legal right to benefit from all or some utilities of a tangible or intangible good that is held by a plurality of legal subjects in a collective way without any person having the power to exclude the rightholder from such benefit. Dusollier, acknowledges that inclusivity is a spectrum and identifies different types of property regimes that display varying degrees of inclusivity. For instance, the public domain—where inclusivity arises through an absence of exclusive property rights—would be located at one end of the inclusivity spectrum while copyleft licenses such as GPL and Creative Commons (CC)—that use contract as a tool to include others in the collective enjoyment of a good subject to exclusive copyright—would be located towards the other end. [7] The inclusive copyright that is proposed in this paper is situated at a mid-point on this spectrum. As elaborated in greater detail in section 4.1 below, it refers to a copyright that is shared among an open and indeterminate community of contributing authors which grants to each of them an equal and symmetrical right to collectively benefit from the utilities of a work (good), without one single author having a power or privilege to exclude another author from such benefit. Unlike in the case of copyleft licenses, here the quality of inclusivity materializes through a positive legal right that is held in rem by each inclusive copyright holder (as opposed to a right in personam that is granted by the holder of an exclusive copyright by contract). Yet, unlike goods in the public domain, inclusive copyright does not denote an absence of exclusive rights. Rather, inclusive copyright grants each rightholder a positive right of ownership in the common work (good) that can be ‘defensively’ enforced to prevent the exclusive appropriation of the work by any person (including any other inclusive copyright holder) and to prevent its use in violation of generally applicable terms and conditions. Thus, the inclusive copyright will comprise a dimension of exclusivity that, unlike the classical notion of exclusive property rights, is not directed towards preserving the individual enjoyment of the work (good) but rather aims to sustain and perpetuate the inclusive and collective enjoyment of the common work (good) over time by preventing its exclusive appropriation. [8]

5

This paper proceeds in four parts. Part 2 describes the Wiki authorship model—which I refer to as authorship carried out under Public Open Collaborative Creation (POCC) model—as a new archetype of collaborative creation that is based on a creation ideology that is collective and inclusive. Part 3 analyses the inability of the existing notion of exclusive copyright to give adequate legal expression to the relationships between persons engaged in the creation process under the POCC model. Part 4 proposes the development of an ‘inclusive’ copyright that would be more suited for giving legal expression to the relationships among the authors of a POCC work. The concept of an inclusive copyright is still at a very early stage of development and many issues relating to its scope, area of application and modalities of enforcement remain unresolved; part 5 provides a glimpse into some of these issues and discusses possible strategies for their resolution.

2. POCC as a new archetype of collaborative creation

6

POCC is a term I coined to describe a collaborative creation model that is steadily gaining in popularity within the digital humanities. I define it as creation taking place through the contributions of a multiplicity of persons under a model of sequential creation, resulting in the production of a literary, artistic or scientific work, which remains in a continuous state of change and development over an undefined period of time. [9] As per the structure of the POCC model, a plurality of authors collaborate in the creation of a single work by modifying and building upon expression contributed by each other within a process of incremental creation. This process of creation takes places within an open-ended time span which allows it to continue over an indefinite period of time. The term ‘work’ is used here to denote that the intellectual content created under a POCC model of authorship would typically display sufficient originality to qualify for copyright protection.

7

At present, the use of the POCC model can be observed in many collaborative creation projects that result in the production of a diverse array of literary, artistic and scientific content. The best-known examples of such creation projects are the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia [10] (hence the term Wiki authorship) and free open-source software (FOSS) creation projects such as VLC [11] and Debian [12]. In addition, it is used for the creation of collaborative fictional stories by the Folding Story [13] platform and This Exquisite Forest [14] project used it in the creation of collaborative graphic art.

8

To illustrate the POCC model better, let us consider the creation process of a Wikipedia article (or ‘page’ as they are commonly referred to). Every Wikipedia article on a given topic is created by a multiplicity of contributors each building upon the expression contributed by previous contributors by means of adding to, modifying and in some instances even overwriting that expression. Even though the individual contributions may differ both in quantitative and qualitative terms, each contribution constitutes an integral step in the creation process. While this sequential creation process results in a literary work that remains in a constant state of evolution it nevertheless succeeds in preserving the work’s character as a single coherent work that, taken as a whole, will qualify for copyright protection at each stage of its evolution. [15]

9

In many cases, the contributions will take the form of ‘tweaks’ or very incremental changes or additions to existing content. This process of ‘tweaking’ is a hallmark of the POCC process and the following example that is based on the creation process of the headnote of the Wikipedia article on ‘Alexander the Great' serves to elucidate this process. [16]

10

In November 2004, Participant ‘T’ makes the following contribution to the headnote.

...Alexander the Great, was one of the most successful military commanders of the Ancient

world

In May 2007, Participant ‘U’ revises it as follows,

...Alexander the Great, was one of the most successful Ancient Greek military commanders of the Ancient world in history

In June 2007, Participant ‘V’ deletes the words ‘Ancient Greek’ as he feels it confuses the sense of what the sentence seeks to convey,

...Alexander the Great, was one of the most successful Ancient Greek military commanders in history

In January 2011, Participant ‘X’ partially re-writes the sentence,

Alexander was known to be undefeated in battle and is considered one of the most successful commanders of all time

11

For the moment, the POCC model is employed in the digital sphere and is primarily used in the creation of digital content over Internet platforms. [17] The genesis of the POCC model within the digital sphere is understandable as the potential for connectivity and networking offered by the Internet and the tools and infrastructure offered by digital technology for collaborative and incremental creation [18] provide the perfect conditions for the model to flourish. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the POCC model has the potential to be used in non-digital offline settings as well, for example in the creation of street art and graffiti and in the creation of music through jamming sessions. Indeed, it is possible to draw comparisons between the POCC model and folkloric traditions of storytelling, indigenous art and traditions of religious discourse. This gives rise to the interesting question whether the POCC model is in fact a completely ‘new’ archetype of authorship or whether it in fact signals the re-emergence of an ancient form of collaborative creation within the digital sphere. [19]

12

The value of the POCC model lies in its ability to harness the skills, talents, knowledge and experience of a large and diverse group of otherwise unconnected individuals from all corners of the globe within a common collaborative value creation endeavour. These individuals are motivated to participate in the POCC process through non-pecuniary considerations [20] such as peer-recognition [21], the enjoyment derived from engaging in a creative pursuit within a community of like-minded individuals and the satisfaction derived from collaborating in the creation of content that generates social, cultural and scientific value. [22]

13

The capacity of the POCC model to direct and sustain a large-scale collaborative authorship effort resulting in high-quality creative output is testified by the Wikipedia project that has matched (and in some respects overtaken) other conventional encyclopaedias published by corporate entities both in terms of comprehensiveness (number of articles and range of disciplines) [23] and reliability. [24] Similarly, VLC software has overtaken Windows Media Player in relation to robustness, sophistication and simplicity of use. [25] Thus, the POCC model of authorship holds significant implications for the democratization of creative production by reflecting a commons-based approach [26] to creation that challenges the traditional market-based creative economy.

2.1. The POCC model

14

The POCC model can be described in relation to four main characteristics: openness, chain of sequential creation [27], creative autonomy and ideology. As will be discussed below, these characteristics imbue POCC authorship with an inclusivity and dynamism that differentiates it from conventional models of collaborative authorship that are recognized by copyright law.

2.1.1. Openness

15

The quality of openness can be described in relation to two aspects of the POCC process.

2.1.1.1. Open creation process.

16

Firstly, the POCC process is ‘open’ to any member of the public, subject to generally applicable terms and conditions of participation. These terms and conditions are twofold. The most important category are terms and conditions that regulate the way in which any member of the public can benefit from the utilities of the POCC work (or any portion thereof) by engaging in the sequential creation process. These terms and conditions are applicable without distinction to persons who seek to use the POCC work both within and (where such use is permitted by the terms and conditions) outside the dedicated platform. They are usually imposed through standard-form open-public licenses (e.g. CC and GPL) but can also take the form of specific terms and conditions that are formulated to fulfil requirements of a particular creation project. For example, Wikipedia articles are subject to a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license that determine the ways in which they can be reproduced, adapted or made available to the public. Any person who wishes to use a Wikipedia article (or any portion thereof) must agree to be bound by the terms of the CC-BY-SA 3.0 license, regardless as to whether the intended use is to be carried out within the Wikipedia platform or outside it. [28] Similarly, in the case of FOSS programs contributors agree to abide by the terms of the GPL license. The choice of applicable license or the formulation of the specific terms and conditions are typically determined by the project initiator [29] although members of the creator community can sometimes be invited to participate in modifying these to suit the changing needs of the project. [30] The second category of terms and conditions is community governance rules that are designed to regulate the behaviour of creators (contributors) who engage in the POCC process. These community governance rules reflect an institutionalized framework of shared norms, goals and standards of conduct. [31] For instance, they could prescribe standards of conduct to be observed by creators in interacting with each other and delineate the nature and scope of the powers and authority vested in individuals empowered to carry out editorial and administrative functions. Such community governance rules are typically associated with creator communities engaging in the POCC authorship process within a dedicated online platform. [32] However, it is possible that they may also apply to diffused creator communities that do not engage in creation within a specific dedicated space but are dispersed both temporally and spatially. By setting out a common framework and/or set of values and ideals, they bind creators together within a common governance framework (and often within a common value system) that serves to create a sense of community among contributors and enables them to develop a common identity (e.g. a common identity as Wikipedians). [33] While the POCC model is not reliant on the existence of a community governance framework or a common value system, these contribute in no small measure towards the sustenance of the POCC process and could be a critical ingredient in ensuring the success of the creation endeavour. Both categories of terms and conditions are capable of enforcement: the first category through legal action (e.g. enforcement of CC licenses in a court of law); and the second through community action (e.g. by ‘blocking’ and thereby excluding any person from continuing to engage in the common creation endeavour). However, as long as an individual abides by the terms of the license and community governance rules, no person has the power or privilege to exclude them from participating in the common creation endeavour. Thus, the borders of the POCC creator community are porous and any individual is able to gain membership of the creator community by agreeing to abide by generally applicable terms and conditions.

2.1.1.2. Open resource

17

Secondly, openness refers to the fact that the work created within the POCC process constitutes an ‘open-resource’ that can be added to, modified and built upon by members of the public both within the POCC process and in some instances even outside it (e.g. in creating stand-alone derivative works that are based on the POCC work but do not become part of the common work). Members of the public who engage in the creation process by adding to, modifying the POCC work or re-using the POCC work or portions thereof in the creation of independent derivative works can be referred to as ‘active users’. In addition, under the POCC model, the work is typically made available to ‘passive’ users who seek to use the content without making further additions or modifications to that work (e.g. a student who wishes to cite a portion of a Wikipedia page in a term paper). Of course, the degree of ‘openness’ of different POCC works can differ depending on the terms on which they are made available for use and re-use. For instance, the Folding Story project allows members of the public to develop and build upon content using the POCC model within the dedicated platform in accordance with specified terms and conditions of use. However, as regards use outside the online platform, the content is made available subject to the exclusive copyright of the respective authors. Therefore, while the POCC work created through the Folding Story project constitutes an ‘open-resource’ as regards the members of the creator community who engage in the POCC process within the dedicated online platform, it comprises a ‘closed-resource’ as regards third parties.

18

The POCC authorship process reflects a collective endeavour within which the contributions of a multitude of otherwise unconnected persons [34] serve to create a single identifiable work that is available for the use and enjoyment of members of the public who agree to abide by generally applicable terms of use. In this sense, it corresponds closely to von Hippel’s model of ‘open collaborative innovation’ (OCI) that has been defined as development projects in which multiple users collaborate and contribute for free and openly share what they develop. [35] However, the fact that this concept has been formulated with reference to innovation economics and the vague terms in which it has been defined makes it unsuitable for founding a legal analysis of POCC authorship.

19

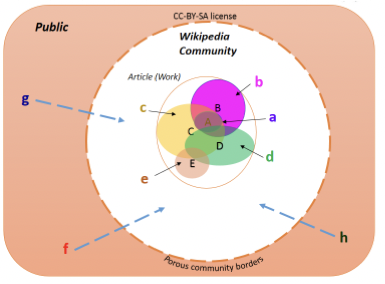

Figure I illustrates the POCC creation process; a, b, c and d being contributors to the creation process (i.e. members of the creator community) and g, f and h being members of the public who are hoping to contribute to the creation process at a future date (i.e. intending to obtain membership of the creator community).

Fig. I: Illustration of POCC process

2.1.2. Chain of sequential creation

20

The POCC process involves a multiplicity of persons building upon and adding to content contributed by each other within a chain of sequential creation. Each contributor dedicates their contribution to the common creation effort to be added to, modified and built upon by downstream contributors. As a result, the contributions made by individual contributors become inseparably linked and intertwined with each other contextually and/or physically. Each contribution depends on preceding contributions for their context and meaning and this results in each contribution (no matter how small) being imbibed with an inherent dynamism, in that, it has the potential to inspire and direct the nature and substance of future contributions along the chain of sequential innovation. The open time-frame that enables the creation process to continue for an indefinite period of time enhances this dynamism by enabling the work to constantly adapt and update itself as an evolving ‘living’ work that can cater to contemporary requirements. Therefore, the POCC model is particularly suited for the creation of content that is in constant need of revision and updating such as FOSS and encyclopedia articles such as Wikipedia.

2.1.3. Creative autonomy

21

The POCC process proceeds in a random and sporadic manner, without a pre-determined creation design (agenda) or consensus among the authors as to the exact nature of the ultimate work. In addition, the POCC model is heterarchical [36] meaning that each contributor enjoys an equal degree of power and authority in determining the direction and outcome of the creation endeavour. Therefore, no person has the power to exercise control over the creative decision-making process or to set a creative agenda for another person. Thus, contributors are able to self-select the nature and scope of their individual contributions by exercising their personal creative judgment. In rare instances, contributions made to the common work may be subject to a process of curation such as in the case of This Exquisite Forest. [37] However, this curation is limited to the purpose of ensuring that only contributions that meet a certain level of quality are absorbed into the common work and do not set a creative agenda or dictate the actual nature and scope of individual contributions. Thus, each contributor exercises a substantial degree of creative freedom and autonomy in determining the nature and scope of the contribution they make. This also means that each contributor has the ability to modify and develop the POCC work in a way that could not have been intended or foreseen by preceding authors. For instance, in the creation of short fiction under a POCC creation model, a character created by an upstream contributor can be developed and modified by a downstream contributor in a way that was neither intended nor foreseen by its initial creator. This absence of a common creative agenda invests the creation process with considerable dynamism as the work is constantly developing in a manner that is serendipitous and unpredictable.

2.1.4. Ideology

22

The POCC model is founded upon an ideology of equality, collectiveness and sharing that is shared and accepted by contributors to the POCC process. This shared ideology and communitarian norms form a powerful incentive for individuals to contribute to the POCC process. [38] Therefore, the preservation and perpetuation of these norms along the chain of sequential creation is a key consideration in ensuring the sustainability of the POCC process.

23

The ideology of equality places each contributor on an equal footing with others and grants equal value to each contribution. Therefore, each contributor obtains an equal claim to the authorship of the work regardless of the value of their individual contribution to the overall work, either in quantitative or qualitative terms. The ideology of collectiveness is reflected through each individual contributor dedicating their expression to the common work that results in that expression becoming intertwined with the expression contributed by others to form a single cohesive work. Thus, the resulting POCC work is the result of a collective creative effort on the part of all contributors. Furthermore, the sequential innovation process proceeds upon a presumption held by each contributor that the value of their individual contribution would be augmented through its combination with other contributions and through modifications and additions effected by downstream contributors in the future. This further enhances the collective nature of the POCC process and gives expression to the ideology of sharing whereby each contributor entertains the expectation of sharing in the benefits of the value created through the contributions made to the work by others. Accordingly, the POCC process not only represents a collaborative endeavour that is designed for the creation of value but also for the collective sharing of that value with other contributors and (usually) with the public at large. [39]

3. Why is exclusive copyright inadequate?

24

Copyright is granted to the author(s) of a work. [40] Thus, the establishment of authorship is the central criterion for the enjoyment of the ownership of copyright over a work.

25

Copyright law conceptualizes authorship as an individual relationship that exists between a person (i.e. an author) and the expression (i.e. work) that is created by that person (or ‘originates’ [41] from them). The work thus created, is deemed to remain static and unchanging with the result that the individual relationship between the author and the expression remains similarly fixed and unchanged. Therefore, the current individualistic notion of authorship in copyright is constructed in relation to a product (i.e. the ‘work’) rather than in relation to the process of creation.

26

This individualistic conception of authorship is underpinned by two dominant theories of copyright law. The labour theory of copyright law (based on the writings of Locke [42]) that justifies copyright protection on the basis of an author’s entitlement to enjoy the fruits of their labour. This is founded on “…the concept of a unique individual who creates something original and is entitled to reap a profit from those labours”. [43] Similarly, the personhood theory of copyright law (derived from the writings of Kant [44] and Hegel [45]) is based on the premise that a work constitutes an artefactual embodiment of the author’s individual personality [46] and that, therefore, its protection under copyright law can be justified as a means of protecting the author’s personality. [47]

27

By attributing the work to the personal intellect of an identifiable author, copyright’s individualistic conception of authorship reinforces the exclusive nature of the right held by that author over the work. As the work is the product of the author’s own individual intellect it is both just and ethical that the author be allowed to reserve the benefits of the utilities of that work (e.g. reproduction, distribution, adaptation) to their own individual enjoyment (i.e. ‘mine not yours’) and be granted an affirmative claim to prevent any other person from benefitting from those utilities without their authorization.

28

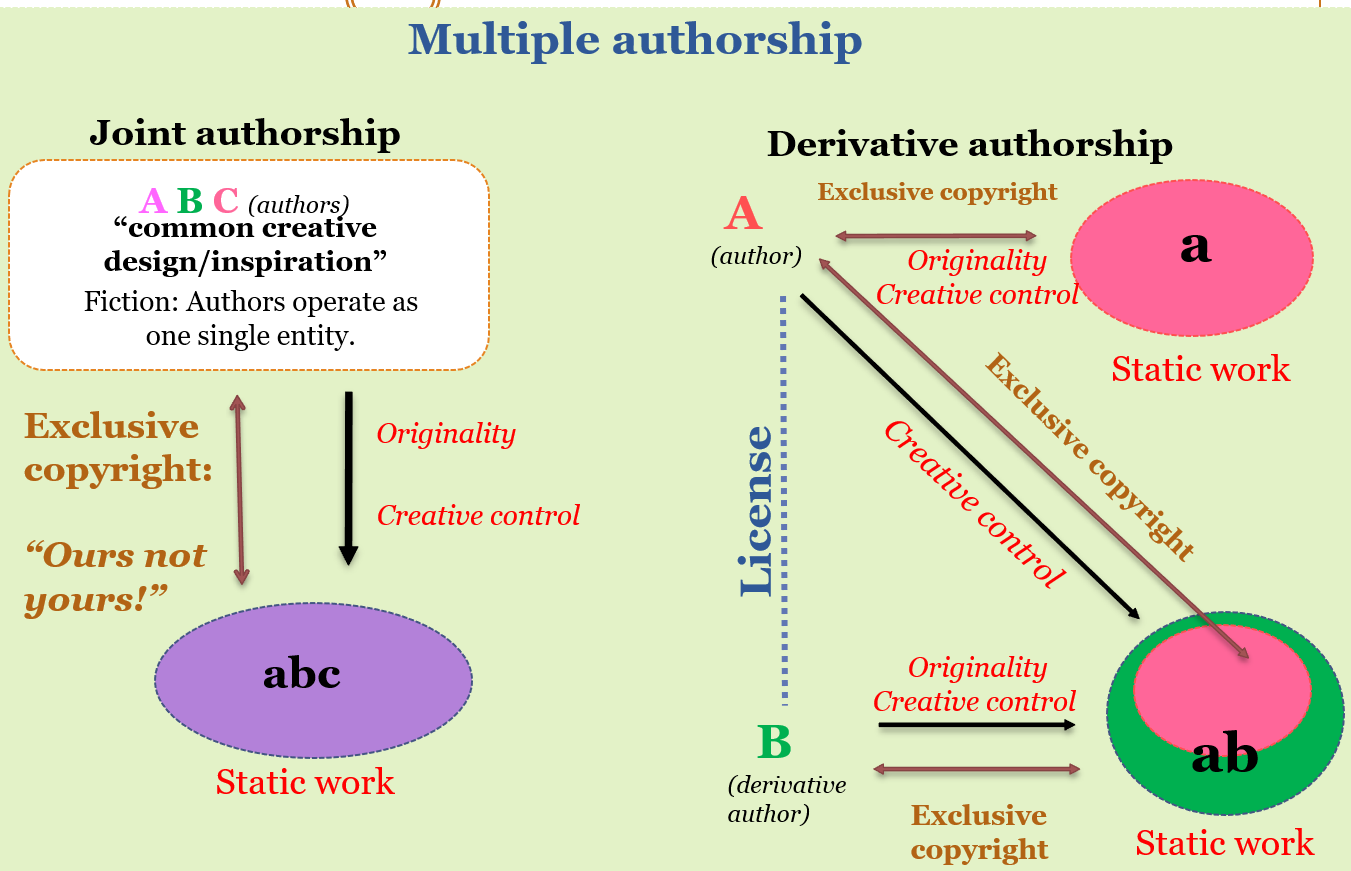

Copyright law’s notion of authorship gives expression to this individualistic bias through three main elements which I refer to as the ‘tripod’ of copyright’s notion of authorship. These are originality, creative control and the existence of a static work. Originality is the primary element that establishes the individual relationship between the author and the work. It pre-supposes the existence of “…a relation of creation between the work and the author.” [48] The second element of creative control refers to the ‘agenda-setting’ ability of the author in determining the final nature and form of the work by exercising control over the creative decision-making process. It thereby foresees the establishment of a direct link between the original expression incorporated in the work and the author’s own intellect and personality. Woodmansee gives expression to this element by noting that copyright conceptualizes an author as “an individual who is solely responsible — and therefore exclusively deserving of credit for the production of a unique work.” [49] The final element of a static work links authorship to a closed, static product which ensures that the individual relationship between the author and their original expression (incorporated in the work) remains unchanged once it has been established. Any further changes or modifications made to that original expression, either by the author themselves or by a third person, will give rise to a new static (derivative) work as opposed to being recognized as a step in the work’s evolution (see Figure II).

29

As will be discussed in section 3.2. this individualistic notion of authorship also permeates copyright’s conception of collaborative authorship that is conceptualized as an individual or distinct relationship that exists between an identifiable group of persons (authors) and the original expression (work) originating from them (see Figure III).

3.1. Inability of a POCC work to fit within the existing categories of collaborative authorship

30

At present, copyright law recognizes three models of collaborative creation: joint, derivative and collective creation. This classification applies consistently across different copyright law systems, albeit with nuances in the ways in which they are defined and interpreted. Authorship and the distribution of exclusive rights over a work involving a plurality of authors is determined according to the model of collaborative creation under which that work has been produced. Therefore, identifying the applicable model of collaborative creation is an important step in determining the persons who obtain copyright over the work and how that copyright can be exercised and enforced. At the moment, copyright law does not offer a catch-all-category (or a category de droit commun) that is equipped to deal with a work that fails to fall within any one of these categories. It is noted that a POCC work would not fit comfortably within any of these existing categories of collaborative authorship as they are currently defined in the copyright law systems of France, the UK and the US.

31

The joint creation model envisions a group of persons collaborating together in the creation of a specific and as yet unfinished work [50] with the creation process automatically coming to an end once the joint work has been realized. Thus, the joint creation model fails to capture the open-ended nature of the POCC process that is not directed towards the production of a static work but rather a dynamic work that can evolve over an indefinite period of time.

32

Similarly, a POCC work cannot be categorized as a derivative work. The derivative creation model envisions the creation of a new work through the modification, alteration or adaptation of a pre-existing work. Thus, the new work ‘derives from’ an existing work and constitutes a work of multiple authorship in the sense that it represents a fusion of expression belonging to the author of the pre-existing work and the author of the derivative work. However, the derivative work constitutes an independent work that exists separately from the pre-existing work and vice versa. Accordingly, the derivative creation model fails to capture the dynamism that is inherent in the POCC model whereby, any contribution that modifies, adapts or builds upon an existing contribution is absorbed into the common work without enjoying a separate existence from it.

33

The collective creation model envisages the creation of a collective work through the compilation or arrangement of the creative contributions made by a multiplicity of authors, within a logical sequence. The characteristic feature of the collective creation model is that the different authors do not collaborate with each other within a common creative endeavor but instead work independently on their individual contributions. These contributions are later collated together to form a single collective work by a specific person who is usually attributed the authorship of the collective work (provided that the compilation and/or arrangement of the different contributions display sufficient originality in order to qualify them as an author). As such, the absence of collaboration among the different authors within the creation process and the fact that these different contributions usually remain separate and distinct from each other, clearly prevents the POCC process from being located within the collective creation model.

3.2. Notion of collaborative authorship in copyright law

34

Of the three models of collaborative creation currently recognized under copyright law, the joint and derivative models of creation give rise to works of plural authorship whereby the authorship over the work is attributed to more than one person. The collective creation model on the other hand, results in the creation of a work of single authorship as the authorship of the work is attributed to the person or entity who is deemed responsible [51] for compiling the individual contributions made by a multitude of authors in order to create the collective work. Thus, at the outset, it is possible to exclude the collective creation model from our analysis of the notion of collaborative authorship in copyright law. I will proceed to analyse the joint and derivative creation models as they are defined and interpreted in the copyright law frameworks of France, the UK and the US to demonstrate how the tripod of copyright’s individualistic notion of authorship permeates the concept of plural authorship in works created under these models of collaborative creation.

3.2.1. The joint creation model

3.2.1.1. Originality

35

The joint creation model refers to the creation of a single static work by merging together the creative efforts of a multiplicity of persons. The copyright over the ensuing work is collectively owned [52] by all persons (co-authors) who have contributed original expression to the work. The attribution of authorship over a work created under a joint model of creation is reliant on a contributor’s ability to establish a direct and individual link to the whole or part of the original expression incorporated in that work. In France, this is expressed through the requirement that each author must make an original creative contribution in the sense that it contains the manifestation of the stamp of the author’s personality. [53] In the UK it is reflected in the condition that each co-author must make an original and significant contribution to the authorship of the work [54] and in the US by the requisite that each co-author must make a contribution that is copyrightable. [55] Thus, in all three systems of copyright law any person who is not able to establish a direct individual link to the original expression incorporated in the work would be denied a claim of co-authorship and consequently precluded from claiming ownership (or co-ownership) of copyright in the work.

3.2.1.2. Creative Control

36

In France, co-authors of a joint work are deemed to engage in creation under a ‘common inspiration’ or ‘spiritual intimacy’ that enables them to work towards a common goal by means of a creative concerted effort. [56] Similarly in the UK, co-authors are deemed to jointly labour together in pursuance of a common goal or in prosecution of a common design. [57] I argue that, as the common inspiration’ or ‘common design’ under which the co-authors labour dictates and directs the original expression that is contributed by each of them to the joint work, this gives rise to a fiction that the group of authors act together as one single entity in pursuance of a common creative agenda in the creation of the joint work. Thus, creative control over the work is deemed to be shared by all co-authors acting as a single organic creative entity that enables the establishment of an individual (in the sense of a ‘distinct’) link between the original expression incorporated in the joint work and the plurality of authors. This fiction therefore allows the creation of a joint work to be subsumed within copyright’s individualistic conception of authorship.

37

Arguably, this element of a common creative agenda is also reflected in US copyright law’s notion of joint authorship in the criterion of ‘mutual intent’, which requires that, at the time of making their individual contributions, each co-author intends that their contribution be merged into inseparable or interdependent parts of a unitary whole. [58] Goldstein opines that this requirement of ‘mutual intent’ essentially mirrors the UK law requirement of the existence of a common design among the authors of a work of joint authorship. Indeed, in the case of Childress v Taylor [59] , the Second Circuit regarded the sharing of creative decision-making authority among authors as a core element in establishing the ‘mutual intent’ criterion. It is logical that the existence of an intention on the part of each co-author that their contribution be absorbed into a single unitary work, compels each contributor to create their own contribution in anticipation of those made by others to ensure that the contributions complement each other. This pre-supposes the existence of some form of pre-agreed common scheme of creation or creative agenda that is shared by the co-authors of the work of joint authorship and therefore unifies them in its prosecution. Accordingly, the criterion of ‘mutual intent’ can also be interpreted as giving rise to a fiction that the co-authors of a joint work act together as a one single entity in the prosecution of a common creative agenda; this yet again locates the authorship of a joint work within copyright law’s individualistic conception of authorship.

38

Independently of the ‘mutual intent’ criterion, the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit has developed a ‘control-based’ test pursuant to which the creative and financial control exercised over a joint work is considered a deciding factor in the establishment of co-authorship. Thus, in the case of Aalmuhammed v Lee [60], the Ninth Circuit held that, the absence of control over creative decision-making is “(…) strong evidence of absence of co-authorship”. On the other hand, in the case of Lindsay v Titanic [61] a high degree of actual control was held to give rise to a presumption of authorship.

3.2.1.3. Static work

39

Once created, the joint work remains closed to further changes and each new addition or modification will result in a separate and independent derivative work as opposed to being absorbed within the joint work. Thus, changes effected to the joint work by subsequent contributors will not affect the legal relationships that exist between the co-authors and the original expression of the work.

3.2.2. The derivative creation model

3.2.2.1. Originality

40

The derivative creation model refers to the creation of a new work by modifying, building upon or adding to the original expression of an existing work and by combining it with ‘new’ original expression. This ‘new’ original expression enables the author of the derivative work to establish an individual link with the work. Accordingly, in French copyright law, the author of the derivative work is required to imbue it with a sufficient degree of independent originality in order to enable it to be protected as a new work of authorship. [62] In UK copyright law, this is framed in terms of the derivative work incorporating a material alteration or embellishment that is original and suffices to make the totality of the work an original work. [63] In US copyright law, the derivative work must demonstrate a sufficient level of originality in the sense that it incorporates a distinguishable and non-trivial variation from the pre-existing work. On the other hand, an individual link is also established between the derivative work and the author of the pre-existing work by reason of the original expression belonging to that pre-existing work which is incorporated in the new derivative work. [64] The copyright over the new derivative work will therefore belong to the author who produces it, subject to the reservation of the rights of the author of the pre-existing work over their own original expression that is incorporated in the derivative work. [65]

3.2.2.2. Creative control

41

In terms of creative control, the author of the pre-existing work is able to exercise negative control over the creation of the derivative work by imposing restrictions and limitations on the nature and extent to which the original expression belonging to the pre-existing work can be added to, modified, built upon and combined with the new original expression contributed by the author of the derivative work. This ability to exercise negative control, enables the author of the pre-existing work to ensure the preservation of their own individual link with the original expression incorporated in the derivative work (for instance by invoking the moral right to integrity to prevent the modification of their original expression in a way that results in an obliteration of their ‘personal stamp’ from that expression). Within the framework of the authorization granted by the author of the pre-existing work, the author of the derivative work is able to exercise positive creative control in terms of determining the way in which the original expression contained in the pre-existing work should be modified, altered and combined with their own original expression to create the new derivative work. Thus, both the author of the pre-existing work and the author of the derivative work can claim an individual relationship to the original expression that is incorporated in that work, thereby rendering the new derivative work a work of plural authorship.

3.2.2.3. Static work

42

Although derivative creation is necessarily an incremental process, existing copyright law artificially compartmentalizes each point in this creation process into a series of separate and static derivative works. Thus, any modification to an existing derivative work will result in the creation of a new derivative work as opposed to being recognized as a point in an evolutionary and incremental process of creation.

Fig. III: Illustration of individual relationship between authors and works of plural authorship

3.3. Why does the POCC authorship model not fit within copyright’s notion of plural authorship?

43

The architecture of the POCC model precludes any single contributor to a POCC work from establishing an individual relationship between themself and the original expression of the work as envisioned by copyright’s conception of individualistic authorship and the tripod of originality, creative control and the existence of a static work.

3.3.1. Originality

44

Not all contributions that build upon existing content would be able to demonstrate sufficient originality as required for establishing authorship under copyright law. For example, within the process of ‘tweaking’ that is commonly used in the creation of POCC works contributions that on their own would fail to satisfy the standard of originality would, through their combination with each other along the process of sequential innovation, give rise to an original copyrightable contribution. In such an instance, it would be difficult to correctly determine the source of that original expression.

45

On the other hand, as upstream contributors are not able to exercise any degree of negative control to limit the ways in which downstream contributors may modify their contributions, it is quite possible that the original expression contributed by an author becomes obliterated [66] from the POCC work in the course of the sequential creation process. Such obliteration would effectively extinguish the individual relationship that author could claim to the POCC work.

3.3.2. Creative control

46

The absence of a pre-determined scheme of creation, the high degree of creative autonomy exercised by each contributor and the random and sporadic nature of the contributions precludes the possibility for any person or group of persons to claim creative control over the creation of the POCC work. The open-ended creation process allows any downstream contributor to change the POCC work in a way that could not have been envisioned or anticipated by an upstream author without those authors being able to control or prevent such changes from being effected. Thus, it is not possible to establish the existence of a common creative agenda that enables contributors to act as a single entity in the prosecution of the common work. In contrast, the POCC model relies on and celebrates the existence of different creative visions that enable the work to constantly evolve in new directions.

47

Furthermore, the format of the POCC model does not allow for the existence of such a common creative agenda by reason of the minimal scope that is available for interaction and discussion among contributors to a POCC work. [67] Contributors may share a consensus as to the general goal of the creation endeavour (e.g. to create an encyclopaedia entry on a particular topic that can serve as an authoritative source of reference on that topic or the creation of a work of fiction or a work of graphic art). They would (and in most instances do) also share a common goal or objective as regards certain technical aspects of the creation process (e.g. writing style, standard of language to be used etc.). However, this cannot be considered as the sharing of a ‘common creation design’ or a ‘spiritual intimacy’. Those terms refer to a consensus and a shared creative vision on the part of joint authors that relate to the nature and form of the original expression that is to be incorporated in the work and thus imply the exercise of shared control over the creative decision-making process. Thus, the existence of a common creation design or spiritual intimacy cannot be reconciled with the POCC process where each contributor makes independent decisions relating to the original expression that is contributed by them and consequently the direction in which the POCC work evolves.

48

As demonstrated by the foregoing discussion, incorporating the POCC work within the existing categories of joint and derivative works would require a radical transformation of the core premise of individuality-based authorship on which they are founded. Furthermore, attempting to fit the POCC model within any of these conventional categories of collaborative authorship recognized under copyright law would lead to different stages of its evolution being artificially compartmentalized, either as successive ‘versions’ of a joint work or as a series of derivative works, or an mixture of both (as a result of different portions of the work being categorized as different works). This would distort the true nature of a POCC work as a dynamic and evolving work that nevertheless forms a cohesive whole. [68]

3.4. Constructing a notion of POCC authorship

49

As Lavik notes, authorship does not possess a timeless quintessence that is independent of human perspectives and purpose. [69] On the contrary, it is a by-product of social, historical and cultural context [70] and as such, is subject to transformation and evolution in accordance with changes in the ways in which creation is carried out and experienced. The following section constructs a new notion of POCC authorship that is founded on the core elements of inclusivity and dynamism.

3.4.1. Inclusivity

50

As envisaged by Dusollier, the term ‘inclusivity’ denotes the quality of a legal right to benefit from all or some utilities of a tangible or intangible good that is held by a plurality of legal subjects in a collective way without any person having the power to exclude the rightholder from such benefit. [71] Thus, it presents a counterpoint to the exclusivity-based notion of individualistic authorship in copyright law. How is this quality of inclusivity reflected in the POCC authorship process?

51

Firstly, the sequential innovation process that is integral to the POCC authorship model relies on the ability of contributors to add to, modify and build upon contributions made by others and sometimes (as in the case of Wikipedia) to even overwrite or delete content contributed by others. As noted in section 2.1.2. above, this cumulative creation process forms the core of the POCC authorship process and reflects an intention on the part of each contributor to dedicate their own individual contribution to a common creation endeavour in the course of which it is absorbed into a common good (i.e. the POCC work) to be used, re-used and enjoyed by all other contributors. Within this collective creation process, individual contributions become contextually inseparable and entwined with each other in terms of relying on preceding and/or succeeding contributions for their context and meaning. This means that, as a matter of practical necessity, contributors are compelled to enjoy the benefits of the utilities of the content contributed by them to the POCC work in a shared and collective manner.

52

Secondly, as noted in section 2.1.4. above, the ideology of POCC authorship is built upon the notions of collectiveness, sharing and equality. This ideology reflects the nature of the POCC process as a collaborative value creation and value sharing endeavour. Pursuant to the concept of equality that underscores the authorship process, each contributor has an equal entitlement to engage in the creation process by using and re-using content contributed to the POCC work by upstream contributors, subject to generally applicable terms and conditions (e.g. CC license) and platform governance rules, without any other person (including the contributors of specific content) having any power or privilege to exclude them from such use or re-use. In turn, upstream contributors expect to share in the benefits of the value created through new expression contributed to the work by downstream contributors, without any downstream contributor having the power or privilege to exclude them from sharing in that value.

53

Thus, the relationship between contributors to the POCC work mirrors the quality of inclusivity in terms of each of them having an equal claim to benefit from the utilities of the POCC work in terms of adding to, modifying, building upon the POCC work and reproducing, distributing communicating and making it available to the public either in whole or in part, subject to generally applicable terms and conditions (e.g. CC license in the case of a Wikipedia article).

54

Accordingly, authorship under the POCC model represents a collaborative value creation and value sharing endeavour wherein authors are compelled to enjoy the utilities of the POCC work in a shared and collective manner, without any single author having a discretionary power to exclude another from benefitting from those utilities.

3.4.2. Dynamism

55

Dynamism relates to two aspects of POCC authorship. First, the POCC process is dynamic in terms of the potential held by each contribution to inspire and direct succeeding contributions and to determine the trajectory of the creation process. Secondly, the output of the POCC process is a dynamic and evolving work as opposed to a static unchanging work. Within this sequential innovation process the expression contributed by a contributor could become obliterated at any point in time thereby disrupting the individual relationship that may be considered to exist between the contributor and the POCC work. The dynamic nature of the POCC work demands that any person who has contributed to the work at any point in its evolution is recognized as having an equal claim to the authorship of the work. This equal claim to authorship is not reliant on the quantitative or qualitative nature of the contribution since a relatively small contribution, which appears unimportant or commonplace at the time at which it is made, may have a significant influence on the work’s evolution based on the way in which it is interpreted and built upon by downstream contributors.

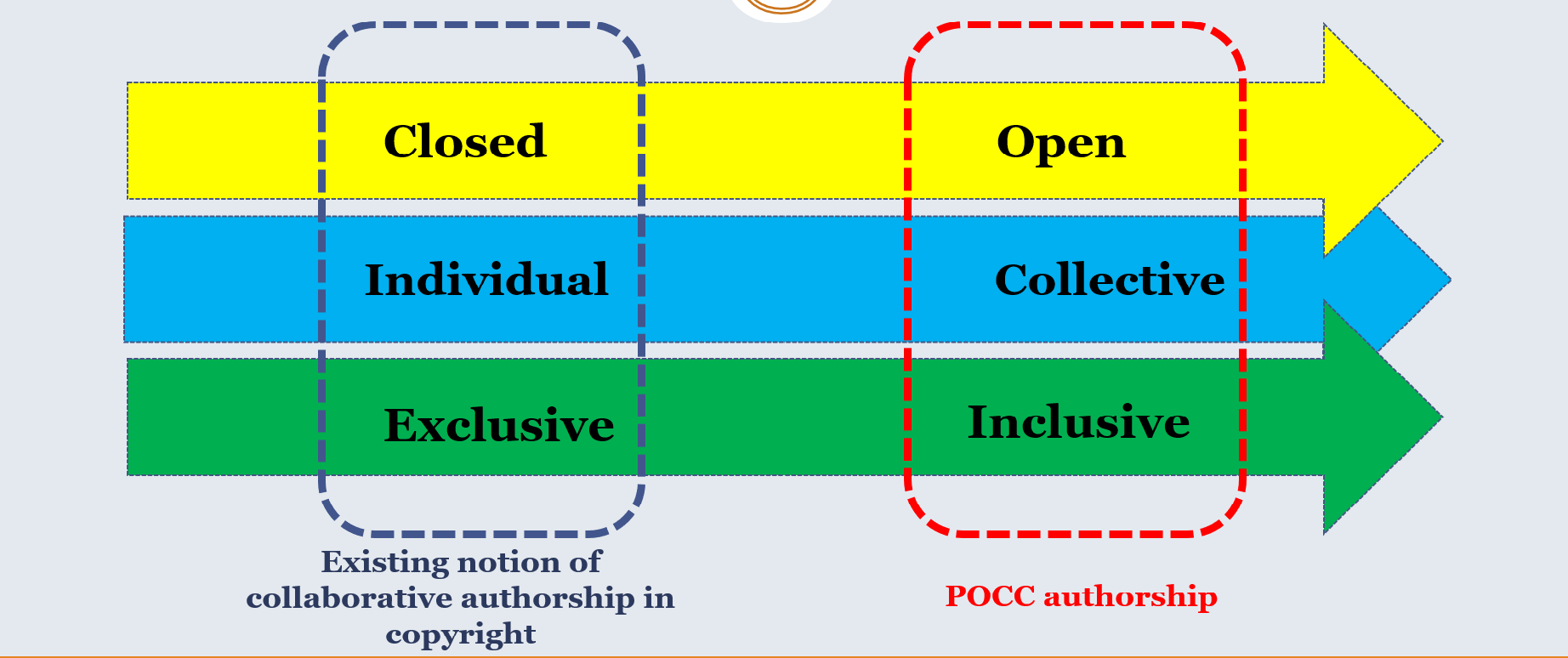

56

Accordingly, the notion of POCC authorship presented here, diverges from copyright’s concept of collaborative authorship by being based on a notion of collective as opposed to individual authorship (see Figure IV). Furthermore, it is not dependent on the establishment of an individual link between the original expression incorporated in the POCC work and the person claiming authorship. Thus, as opposed to the conventional notion of authorship in copyright law the notion of POCC authorship needs to be conceptualized as a relationship that exists between a person (i.e. an author) and an incremental process of creative exchange (i.e. the POCC process) that culminates in the production of a dynamic and evolving work (i.e. the POCC work).

Fig IV: POCC as a new archetype of collaborative authorship

57

Therefore, the notion of POCC authorship presents a new archetype of collaborative authorship that is open, collective and inclusive. The existing exclusivity-based copyright law that is founded upon the conventional closed, individualistic notion of collaborative authorship does not have the capacity to give legal expression to the inclusivity that is inherent in the relationships among the authors of a POCC work. Nor can it adequately capture the dynamism of the POCC work and the temporal dimension of rights of authorship over the evolving POCC work.

3.5. Inadequacy of exclusive copyright in giving expression to inclusivity and dynamism in POCC authorship.

58

As noted in the foregoing discussion, within the POCC authorship process, the contributions of each author are dedicated to the common creation endeavour. In the course of the sequential innovation process, the original expression contributed by each individual author becomes inextricably linked in such a manner that prevents any author from benefitting from the utilities of the original expression created by them without also benefitting from the original expression created by another. The individual copyrights held by contributors over the original expression contributed by them become similarly intertwined in a manner that precludes any single contributing author from exercising or enforcing their copyright without encroaching upon the copyright belonging to another. Thus, the final POCC work is subject to a web of copyrights, the individual exercise and enforcement of which would give rise to a host of ideological and practical problems. This section will explore the impact of the application of exclusivity-based copyright law to a POCC work as regards the exercise and enforcement of copyright over a POCC work. It will focus on the implications for the copyright clearance procedure (i.e. the ability of an individual to obtain authorization to modify and build upon the POCC work) and the ability of an author(s) of the POCC work to bring a legal action against the infringement of their rights (both copyright and contractual rights) in the POCC work.

59

As noted above, the application of exclusive copyright would lead to different stages of evolution of a POCC work being artificially compartmentalized into a series of separate static works that may be categorized either as joint works or as derivative works or even as a mixture of both. This would result in the fragmentation of copyright over the POCC work among a multiplicity of authors. The nature and extent of the exclusive copyright granted to these individual authors over the work would differ according to whether their particular means of collaboration within the POCC creation process leads to their classification as a co-author of a joint work or as an author of a derivative work. As discussed below, the granting of an exclusive copyright to each author over their specific contribution to the work would go against the ideological framework of inclusivity on which the POCC authorship model is based and create inefficiencies relating to the exercise and enforcement of copyright over the POCC work. In the long-term it would also threaten the sustainability of the POCC process.

60

Under both joint and derivative authorship models, exclusive copyright grants to each individual author (i.e. co-author of a joint work or author of a derivative work) a copyright that can be exercised individually and according to personal discretion. For instance, under the copyright law of the UK the co-authors of a work of joint authorship are deemed to hold copyright over the joint work as ‘tenants in common’. [72] This means that the exploitation of the work by a co-author or the licensing of such exploitation to a third party requires the authorization of all co-authors. [73] The same principle applies in French copyright law where the exploitation of the joint work is required to take place in accordance with the principle of unanimity (accord commun). [74] This would mean that in the UK and France (unless the POCC work has been made available to the public under an open public license such as CC or GPL) any downstream author who wishes to engage in the sequential creation process in relation to a particular portion of content belonging to the POCC work would need to identify all authors who have copyright over that portion of the content and to individually obtain their authorization to use such content for the purpose of participating in the POCC authorship process. [75] The same holds true as regards derivative works, as the copyright law systems in all three jurisdictions hold that any addition to or modification of a derivative work (i.e. the creation of a further derivative version) requires authorization of the author of the derivative work as well as the authors of all pre-existing works on which the derivative work is based.

61

The fragmentation of exclusive copyright over the POCC work among a multitude of authors and the need to obtain their individual authorization prior to adding to or modifying the POCC work within the sequential innovation process can result in several problems and inefficiencies.

3.5.1. Copyright clearance

62

Firstly, it would lead to an increase in the transaction costs relating to the license clearing process and thereby create inefficiencies regarding the exploitation of the POCC work. For instance, where the POCC work is made available under an open public license (e.g. CC or GPL) any user who wishes to exploit the POCC work or any portion thereof in a manner that is not covered under the terms of that license will need to identify and obtain the authorization of each contributing author who holds a copyright over the work or over that particular portion. Secondly, it would mean that the authorization granted to a downstream contributor to use the content belonging to the POCC work stems from a web of licenses granted by a plurality of copyright holders. This could give rise to serious inefficiencies (e.g. holes in the web of licenses, incompatibility among licenses) in the enforcement of the license terms in the event of a possible violation. [76] Thirdly, it would allow any author to block the sequential creation process either by preventing downstream contributors from modifying or building upon the specific expression over which they hold copyright or, by granting their authorization subject to conditions that restrict the creative freedom and autonomy of downstream contributors. The capacity of an individual author to disrupt the sequential innovation process by refusing to grant authorization to downstream contributors to modify the expression contributed by them to the POCC work poses a serious risk to the sustainability of POCC process. Furthermore, it would create an asymmetry in the entitlements held by different authors over the POCC work that negates the inclusivity inherent in the POCC process. For instance, an author who has contributed a larger or qualitatively more important portion of the work would be able to exercise greater control over the work’s future development process in comparison with other authors. Similarly, upstream authors would exercise greater control over the work’s development in comparison with downstream authors.

63

On the other hand, while US copyright law also deems that owners of a joint work enjoy copyright as ‘tenants in common’, in contrast to the UK and France, each co-author is entitled to independently exploit the joint work without the need to obtain the authorization of the other co-authors. Thus, a co-author may also unilaterally grant a non-exclusive license to a third party to exploit the work without the authorization of the other co-authors, and if necessary, even overriding their objections. [77] In doing so, the co-author is not bound by any fiduciary duties to exercise their copyright in a way that is not detrimental to the ability of other co-authors to benefit from the utilities of the work. [78] While the US approach dispenses with the difficulties of license clearance and prevents the exercise of exclusive copyright by individual contributing authors to a POCC work to block the sequential creation process, it also means that any single contributing author would be able to exercise exclusive copyright over the work in a manner that impedes the others from fully enjoying the benefits of the utilities of the POCC work. It would further enable a contributing author to exploit the POCC work in a manner that is contrary to the fundamental values of sharing and openness on which the POCC authorship process is founded. [79]

3.5.2. Action for copyright infringement

64

The individualistic approach to authorship under exclusive copyright also means that any contributing author of the POCC work who wishes to bring an action for infringement of copyright over that work would be required to establish their status as an author (i.e. co-authorship of joint work or authorship of derivative work) in order to establish legal standing (locus standi) to bring the action. This would give rise to difficulties relating to the determination of legal standing when the copyright infringement claim is brought in relation to a specific portion of the POCC work. In such a case the question arises whether any co-author of the work would have legal standing to bring the action for infringement or if only those persons who are able to establish co-authorship or derivative authorship over that specific portion would be able to establish legal standing. On the other hand, what would be the status of an author who has in fact made an original contribution to the POCC work that has since become obliterated in the course of the sequential creation process? Would they still be able to claim legal standing based on the original expression contributed to the POCC work at a certain point in its evolution, or would the obliteration of their original expression also lead to a loss or extinguishment of copyright over the POCC work, thereby precluding them from establishing legal standing?

3.6. Inadequacy of open public (copyleft) licenses

65

The CC-SA (Creative Commons licenses with the ‘Share-Alike’ component) and GPL licenses constitute legal tools that can be used for securing the perpetuation of the inclusive copyright along the chain of sequential innovation. The copyleft requirement that is incorporated in these licenses ensures the sustenance of inclusivity by preventing any person from appropriating the POCC work (or any portion thereof) to their own exclusive use and by ensuring that any original expression that is added to the POCC work becomes a part of the inclusive good (or resource) that can be modified and built upon by downstream contributors. [80]

66

Open public licenses constitute standard-form royalty-free licenses that allow any member of the public to use and exploit copyright protected content in specifically defined ways, while allowing the owner of the copyright to reserve certain forms of exploitation to their own exclusive use. The licenses are irrevocable and perpetual (i.e. valid for an infinite period of time). Accordingly, any person is free to reproduce, distribute and transmit the work or any portion thereof as long as they respect the terms and conditions of the license.

67

The application of an open public license obviates the need for each potential user of a POCC work to individually obtain the authorization of each and every person who holds copyright over that content as a pre-condition to participating in the POCC authorship process. As such, it is a successful technical solution to the problem of license clearance and enables the smooth functioning of the process of sequential innovation associated with the POCC creation process.

68

Nevertheless, open public licenses rely upon the traditional copyright law framework for their own legal validity. For example, questions relating to the scope of rights granted under the license and issues relating to the legal title and ownership of rights for the purposes of enforcement will be determined within the scope of the traditional copyright law framework. Accordingly, under an open public license, each author of a POCC work will individually grant a license to a downstream contributor to use the content in which they hold a copyright in ways that are permitted under the license. This leads to the creation of a web of licenses that preserves the attendant inefficiencies relating to enforceability. Although they constitute useful legal tools for sustaining the perpetuation of inclusivity and collectiveness of the POCC process along the chain of sequential creation, open public-licenses do not offer a remedy for the inefficiencies arising from copyright fragmentation for the enforcement of copyright.

4. The case for an inclusive copyright

69

Taking into account the increasing importance of the POCC authorship model as an instrument for the creation of socially valuable content and the promotion of social dialogue, there is a need to revisit the existing exclusivity-based narrative of copyright law and to re-interpret copyright in a way that gives legal effect to the inclusivity inherent in the legal relations between persons engaged in the POCC authorship process. Such re-interpretation should be carried out especially keeping in mind the need to ensure more effective enforcement of copyright over the POCC work and the perpetuation of the quality of inclusivity along the chain of sequential creation.

70

As noted above, within the POCC authorship process, the individual contributions made by contributing authors to the POCC work become contextually inseparable and entwined with each other. The copyright held by those contributing authors over their individual contributions become similarly entwined thereby compelling authors to exercise and enjoy the copyright held by them over the POCC work in a collective manner as opposed to each author individually enjoying their copyright to the exclusion of others. Thus, the POCC authorship process demands a shift from the existing individualistic paradigm of copyright as an instrument for exclusion to a collective paradigm that is based on inclusion. It is noted that the communicational theory [81] of copyright law, which upholds the function of copyright as an instrument for advancing social enrichment through dialogic interaction and supports the creative and flexible interpretation of existing concepts and rules of copyright law to enable copyright to fulfil this function, provides a suitable normative framework for the development of such an inclusive copyright.

4.1. Concept of an ‘inclusive’ copyright

71

As discussed in section 1. above, Dusollier’s concept of an ‘inclusive’ property right is based on two key characteristics: (a) a legal right to a good that is held by a plurality of persons that is characterised by the collective enjoyment of the utilities of that good; and (b) an absence of a power or privilege on the part of the owner of the inclusive property right to exclude any other person having ownership of the same inclusive property right from benefitting from the utilities of the good. This denotes that an inclusive property right would grant each rightholder an equal and symmetrical right to collectively benefit from the utilities of the good without any single rightholder having a power or privilege to exclude any other rightholder from benefitting from those utilities. [82] Building upon this notion, I propose an ‘inclusive’ copyright that is held by each contributing author over a POCC work which would grant them an equal and symmetrical right to enjoy the utilities (e.g. reproduction, adaptation, distribution, communication and making available to the public) of that copyright protected work collectively with the other contributing authors, without any other contributing author having the ability to exclude them from benefitting from those utilities. The inclusive copyright holder would have the right to reproduce, distribute, adapt (including the creation of derivative works), make available and communicate to the public, the POCC work (either in whole or in part) in any manner, as long as the use of the POCC work does not have the effect of preventing any other contributing author from benefitting from those utilities of the POCC work.

72

The inclusive copyright would also grant authors the right to authorize any other third person to benefit from these utilities in accordance with the generally applicable terms and conditions (e.g. open public licenses) under which the POCC work is made available to the public.

73

The inclusive copyright is designed to include other persons in collectively enjoying the benefits of the common work. As will be discussed below in section 4.2., its enforcement will be ‘defensive’ as its effect would be to prevent any person from appropriating the POCC work (or any portion thereof) to their own exclusive use or to prevent any person from using the POCC work in violation of the generally applicable terms and conditions under which it has been made available to the public. This is contrasted with existing exclusive copyright and its enforcement mechanism that is ‘offensive’ in the sense that it is aimed towards excluding any outside persons from benefitting from the utilities of the copyright protected work and for reserving those utilities to the exclusive enjoyment of the copyright holder.

4.2. Nature and scope

4.2.1. Who can obtain an inclusive copyright?

74

The inclusive copyright would vest in any person who contributes to the ‘expression’ of the POCC work at any stage of its evolution provided that the contribution has been integrated into that work. The requirement of contributing to the ‘expression’ of the POCC work would serve as a delimiting factor that reserves the enjoyment of the inclusive copyright to persons who have contributed to the authorship process as opposed to those whose contributions are merely of a technical (as opposed to a creative) nature (e.g. the correction of grammatical errors or spelling mistakes) or is peripheral to the authorship process without directly contributing to it (e.g. the contribution of ideas or research). Thus, in order to obtain an inclusive copyright in the POCC work, it is not required that the contribution made by a person qualifies as original expression in the sense that it is independently copyrightable. It suffices that the contribution is made towards the expression of the work and is therefore directly linked to the authorship process.

75

The term ‘integrated’ refers to the fact that at some point in the sequential creation process the contribution made to the expression of the POCC work has been incorporated into the work in the sense that it has been accepted by the creator community as being a legitimate step in the POCC authorship process. This would not be the case if, for example, the original expression has been removed by an editor (or other authorized person) or otherwise rejected for being an act of vandalism or for being contrary to community guidelines and platform policy. On the other hand, once the contribution has been integrated into the POCC work, its obliteration over the course of the sequential innovation process (or even its deletion or overwriting by a succeeding contributor where this is permitted under the terms and conditions of participation in the POCC process) would not result in the loss or extinguishment of the inclusive copyright held by that contributing author in the POCC work. This is because the claim to authorship of a POCC work does not stem from the individual relationship that subsists between the author and the original expression contributed to the work. Rather, it is rather based on the author’s participation in the POCC process through contribution to the expression of the work at a certain point in the work’s evolution. The essence of the POCC process is the incremental creation process within which contributing authors enjoy creative freedom and autonomy to build upon and modify content contributed by previous authors. The gradual obliteration of a contribution through improvements effected by succeeding contributors is a core feature of the POCC process and divesting a person of authorship status on the grounds of such obliteration would go against the rationale of POCC authorship. It would also allow space for gaming in the sense that any person who wished to divest a contributing author of copyright could maliciously delete or overwrite the contribution made by them. In addition, it would create uncertainty in the determination of copyright ownership in a POCC work. For example, imagine that the contribution made by an author of a POCC work who brings an action for the enforcement of inclusive copyright becomes obliterated during the course of the litigation process. Would this mean that they lose legal standing in the action?

4.2.2. Temporal dimension

76

In view of the evolutionary nature of a POCC work, it is necessary to recognize that the inclusive copyright extends to the entirety of the work (as opposed to the actual portion of the work in which the author’s contribution was integrated). One consequence of this is that the inclusive copyright held by a contributing author would extend to the original expression that forms a part of the POCC work, both before and after obtaining inclusive copyright. Thus, when a person contributes to the expression of the POCC work at time ‘X’, the inclusive copyright they obtain over the work at that time should grant the ability to benefit from the utilities of any original expression contributed to the work both before and after time ‘X’. This means that the inclusive copyright would extend to original expression that formed a part of the POCC work prior to the date on which they obtained inclusive copyright as well as to any contributions that have been made afterwards, including those that may be made in the future. Thus, the inclusive copyright would have a temporal dimension to it. This is based on the premise that the POCC work, although an evolving entity, constitutes a single work that is owned by all authors collectively. This would also give rise to a legitimate expectation on the part of the holder of the inclusive copyright to benefit from the value created by contributions made to the POCC work by other contributors at any point in the evolution of the POCC work, regardless as to whether that contribution has been made before the obtaining of the inclusive copyright over the work or after.

77

Nevertheless, it is necessary to make a distinction between contributions that are made to the POCC work in the sense of being integrated into the POCC work (by modifying, adding to and developing on existing content) and free-standing derivative creations that are based on the POCC work (or any portion thereof) but are meant to form separate and independent works on their own and are therefore not intended to form a part of the POCC work. Such derivative creations would not be considered as a part of the POCC work nor would their creation be considered to form a part of the POCC authorship process. Therefore, the inclusive copyright held by authors of the POCC work would not extend to such free-standing derivative works. Similarly, the author of the free-standing derivative work would not obtain an inclusive copyright over the POCC work but merely a license to use the content belonging to the POCC work in the creation of the new derivative work. The failure to make this distinction would mean that creators who wish to use the POCC work in their derivative creations, but do not wish to engage within the POCC creation process or to dedicate their original expression to the common creative endeavour, would be drawn into the POCC authorship process against their will and be forced to grant an inclusive copyright over the original expression contributed by them in creating the derivative work. This would then, serve as a disincentive to such persons from using the POCC work in the creation of new free-standing derivative works. Therefore, this limitation of the scope of the inclusive copyright is meant to incentivize persons who do not wish to participate in the POCC authorship process from creatively interacting with the POCC work in socially valuable ways, which thereby promotes the process of dialogic authorship.

4.2.3. Duration of protection

78